At the 39th Joint Doctrine Planning Conference, a semiannual meeting on topics related to military doctrine and planning held in May 2007, a contractor for Booz Allan Hamilton named Paul Schuh gave a short presentation discussing doctrinal issues related to “cyberspace” and the military’s increasing effort to define its operations involving computer networks. Schuh, who would later become chief of the Doctrine Branch at U.S. Cyber Command, argued that military terminology related to cyberspace operations was inadequate and failed to address the expansive nature of cyberspace. According to Schuh, the existing definition of cyberspace as “the notional environment in which digitized information is communicated over computer networks” was imprecise. Instead, he proposed that cyberspace be defined as “a domain characterized by the use of electronics and the electromagnetic spectrum to store, modify, and exchange data via networked systems and associated physical infrastructures.”

Amid the disagreements about “notional environments” and “operational domains,” Schuh informed the conference that “experience gleaned from recent cyberspace operations” had revealed “the necessity for development of a lexicon to accommodate cyberspace operations, cyber warfare and various related terms” such as “weapons consequence” or “target vulnerability.” The lexicon needed to explain how the “‘four D’s (deny, degrade, disrupt, destroy)” and other core terms in military terminology could be applied to cyber weapons. The document that would later be produced to fill this void is The Cyber Warfare Lexicon, a relatively short compendium designed to “consolidate the core terminology of cyberspace operations.” Produced by the U.S. Strategic Command’s Joint Functional Command Component – Network Warfare, a predecessor to the current U.S. Cyber Command, the lexicon documents early attempts by the U.S. military to define its own cyber operations and place them within the larger context of traditional warfighting. A version of the lexicon from January 2009 obtained by Public Intelligence includes a complete listing of terms related to the process of creating, classifying and analyzing the effects of cyber weapons. An attachment to the lexicon includes a series of discussions on the evolution of military commanders’ conceptual understanding of cyber warfare and its accompanying terminology, attempting to align the actions of software with the outcomes of traditional weaponry.

Defining Cyber Warfare

One of the primary reasons for creating a lexicon devoted to cyber warfare is that there are “significant underlying differences” between traditional military operations and so-called “non-traditional weapons” such as those employed in cyber warfare. The lexicon was intended to reduce these differences by integrating and standardizing the “use of these non-traditional weapons” while providing “developers, testers, planners, targeteers, decision-makers, and battlefield operators . . . a comprehensive but flexible cyber lexicon that accounts for the unique aspects of cyber warfare while minimizing the requirement to learn new terms for each new technology of the future.” Described as a Language to Support the Development, Testing, Planning, and Employment of Cyber Weapons and Other Modern Warfare Capabilities, the lexicon is designed to facilitate the construction and employment of cyber weapons:

The cyber warfare community needs a precise language that both meets their unique requirements and allows them to interoperate in a world historically dominated by kinetic warfare. Mission planners must be able to discuss cyber weapons with their commanders, the intelligence analysts, the targeteers, and the operators, using terms that will be understood not just because they have been defined somewhere in doctrine, but also because they make sense. Giving the weapons planners a well-founded lexicon enables them to have far-reaching discussions about all manner of weapons and make important decisions with a significantly reduced likelihood of misunderstanding and operational error.

To understand what exactly constitutes a cyber weapon and what makes it so different from the kind of weapons employed in traditional warfare, it is important to understand the objectives of cyber warfare. Cyber warfare is defined in the lexicon as the creation of “effects in and through cyberspace in support of a combatant commander’s military objectives, to ensure friendly forces freedom of action in cyberspace while denying adversaries these same freedoms.” This can be accomplished through cyber attacks, cyber defense as well as cyber exploitation, with each option providing its own unique set of associated capabilities and potential outcomes. Cyber attacks bare the greatest resemblance to popular notions of cyber war, incorporating actions to “deny or manipulate information and/or infrastructure in cyberspace” through methods like a computer network attack (CNA) that are intended to “disrupt, deny, degrade, or destroy the information within computers and computer networks and/or the computers/networks themselves.” Cyber defense is primarily focused on defending U.S. military networks from similar attacks conducted by other nations or non-state actors and protecting the integrity of the Department of Defense’s Global Information Grid (GIG) which carries military communications worldwide. Cyber exploitation is focused primarily on the collection of intelligence and other useful data from targeted computer systems to enable improved “threat recognition” that can contribute to future operations in cyberspace.

These components of cyber warfare rely on capabilities that are used to construct cyber weapon systems. A cyber warfare capability is a “device, computer program or technique” that includes any combination of “software, firmware, and hardware” that is “designed to create an effect in cyberspace, but has not been weaponized.” Weaponization is a process that takes these capabilities and implements “control methods, test and evaluation, safeguards, security classification guidance, interface/delivery method” and other tactical considerations to ensure that the capability can be properly employed to produce the intended effect. A completed cyber weapon system is a combination of one or more of these capabilities that have been weaponized and are ready for deployment. These weapons can then be categorized based upon specific uses and issues related to their employment, such as who is authorized to use them. One suggested schema in the lexicon provides three categories: the first for weapons that require approval from the combatant commander, a second for weapons that are pre-approved for specific uses and a third that requires the approval of the President or Secretary of Defense before the weapon can be utilized.

Brig. Gen. Robert Brooks, director of the Massachusetts Air National Guard gets a eyes-on 3D tutorial of how to analyze data in the Virtual Reality Center at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, during the 2014 Cyber Shield Exercise held in May.

One of the “Discussions on Cyberspace Operations” contained in the lexicon follows the military’s historical apprehension toward describing software programs and other cyber capabilities as weapons. Throughout the early 1990s, the term “tool” was widely favored in the initial phases of the military’s cyber warfare mission. One reason for this reluctance was military commanders’ concerns about the lack of authority under Title 10 for conducting cyber operations. However, given that there are six “Joint functions” recognized in military doctrine “C2 [command and control], Intel, Fires, Maneuver, Protection and Sustainment,” the use of any offensive cyber capabilities “unquestionably” is a form of fires, making the cyber capability itself a kind of weapon. The idea that software and computer hardware could be considered a weapon is further complicated by the fact that many offensive cyber capabilities consist of nothing more than “cyber techniques” that involve “keystrokes, but where no hardware or software is introduced into the target system.” When “last minute changes in the target render the approved weapon inert, an operator might need to use cyber techniques to complete an assigned mission, particularly one that has been approved for effect or objective,” making the certification process and training of the “operator” critical to considering cyber capabilities as a “weapon system.” There must be control methods, testing and evaluation, safeguards, certified personnel, mission logs, a concept of operations as well as tactics, techniques and procedures on how to employ the weapon system. This is similar to the situation with conventional weapons as “the very first M-16 rifle ever made, while a ‘weapon’ in the dictionary sense of the word, was not deployed until it was operationally tested, had a training program, spare parts inventory, etc.” It was only after this process that “each new M-16 was part of a ‘weapon system’ and could be crated and shipped to the front lines directly from the assembly line.”

Cyber Weapons and Their Effects

A fundamental distinction discussed in the lexicon, one which separates cyber weapons from those used in conventional warfare, is the distinction between kinetic and non-kinetic weaponry. Kinetic weapons are those that “use forces of dynamic motion and/or energy upon material bodies” whereas non-kinetic weapons are those that “create their effects based upon the laws of logic or principles other than the laws of physics.” Within each of these broad categories, there are further distinctions based upon the lethality of the weapon being described. For example, a Mark-84 bomb is an example of a lethal kinetic weapon capable of inflicting physical damage to material entities based upon the use of motion and force. The Active Denial System, a directed-energy weapon which uses millimeter waves to create a sensation of heat on the skin of human targets, is an example of a non-lethal kinetic weapon. As a non-kinetic weapon creates its effect through the use of logic or other principles, the category necessarily encompasses a much wider array of weapon systems from diverse fields like information warfare and psychological operations. Biological and chemical weapons are examples of lethal non-kinetic weapons that rely upon biological factors rather than physical force to create their effect. Computer network attack (CNA) software, on the other hand, is an example of a non-lethal non-kinetic weapon, creating an effect based solely on the logical operations it performs on a targeted computer system.

While cyber weapons are considered to be non-lethal in their effects, this doesn’t mean that non-lethal weapons are “required to have zero probability of causing fatalities, permanent injuries, or destruction.” To better understand the effects that non-lethal non-kinetic weapons can have, the lexicon attempts to align cyber weapons with the traditional terminology of the “Four D’s” used throughout the information operations community: deny, destroy, degrade and disrupt. One discussion in the lexicon introduces a construct to understand these effects in terms of a scope, level and time of “denial” in a targeted system, causing “reduction, restriction, or refusal of target operations.” Using this framework, “degrade, disrupt, and destroy” would all be considered different forms of denial that have varying scopes. Disrupt introduces a “time aspect of denial” and degrade adds an “amount or level of denial.” The final term “destroy” is saved for the “special case that includes the maximum time and maximum amount of denial.” The lexicon even proposes a function for calculating denial:

Quantitatively, denial (D) can be expressed as a function of scope (s), level (l), and time (t), i.e. D(s,l,t). Defining effects in this manner makes it clear to the planning staff that each of the parameters of the function must be considered and specified as necessary as indicated by, or derived from, commander’s objective. As the level (l) or amount approaches 100% and time (t) approaches infinity, destruction is achieved.

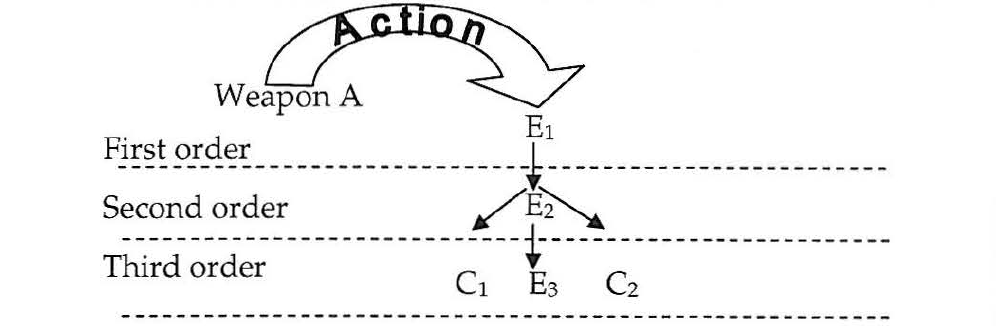

The true effects of a cyber weapon often differ significantly from simply denying or even destroying an enemy system. Every weapon “takes an action” when it is triggered and this action is “intended to have an effect.” For a traditional bomb, that action is a “kinetic explosion and the effect is normally target damage,” whereas a cyber weapon may result in “the execution of some software and the effects, some form of denial or manipulation.” However, weapons also have “outcomes that are not expected and are not required to achieve the objective.” The lexicon describes these as indirect effects that can result in consequences for unintended targets. When these consequences affect unlawful targets or cause “damage to persons or objects that would not be lawful military targets,” they are considered “collateral effects” that are similar to the traditional notion of collateral damage.

Vulnerabilities and Target States

Vulnerabilities and Target States

Past worries about collateral damage from cyber weapons have proven to be well founded. In the summer of 2010, copies of an unknown computer worm began replicating throughout the internet using a vulnerability in Microsoft Windows to find its way into the control systems of major corporations like Chevron. However, the malicious program was not the work of Chinese hackers or sophisticated cyber criminals, it was a cyber weapon called Stuxnet created as part of a joint U.S. and Israeli intelligence operation targeting Iran’s nuclear program that was codenamed “Olympic Games.” Stuxnet would later claim other unintended targets, including a Russian nuclear power plant. Unintended effects associated with cyber weapons are dangerous for a number of reasons, including the risk that an adversary might be able to use the weapon, once discovered, against the originator of the attack. According to the lexicon, these vulnerabilities of cyber weapons can be separated into six distinct categories:

- (U//FOUO) Detectability risk – The risk that a weapon will be unable to elude discovery or suspicion of its existence. This includes the adverse illumination risk of hardware weapons.

- (U//FOUO) Attribution risk – The risk that the discoverer of a weapon or weapon data will be able to identify the source and/or originator of the attack or the source of the weapon used in the attack.

- (U//FOUO) Co-optability risk – The risk that, once discovered, the weapon or its fires will be able to be recruited, used, or reused without authorization.

- (U//FOUO) Security Vulnerability risk – The risk that, once discovered, an unauthorized user could uncover a security vulnerability in the weapon that allows access to resources of the weapon or its launch platform. This includes the risk of an adversary establishing covert channels over a weapon’s C2 link.

- (U//FOUO) Misuse risk – The risk that the weapon can be configured such that an authorized user could unintentionally use it improperly, insecurely, unsafely, etc.

- (U//FOUO) Policy, Law, & Regulation (PLR) risk – The risk that the weapon can be configured such that an authorized user could intentionally use it in violation of existing policy, laws, and regulations.

These vulnerabilities are “mostly unfamiliar to the kinetic weapons community, and are due to the complexity of the weapons, the dynamic nature of the ‘atmosphere’ of cyberspace, and the difficulty of gathering detailed intelligence about cyber targets.” A discussion on cyber weapon vulnerabilities in the lexicon argues that “the crowded nature of cyberspace and the proliferation of anonymizing technologies can work to both our advantage and disadvantage, in that attribution can be very difficult for both our adversaries and ourselves.” Once a network target has been “accessed and subverted,” the implanted cyber weapon should be “considered like a mine or an improvised explosive device (lED) where there are no longer any delivery considerations for the weapon, but only survivability and transferring of commands and updates.”

In several portions of the lexicon, attacking unaffiliated infrastructure that happens to be used by an adversary is discussed as a viable means of creating a “second order” effect on the target. For example, if “privileged access in not possible, we may still be able to create our desired effect in the first order by using public access to the target” such as “a distributed denial of service (DDOS) that floods a port on the target.” When the intended target “cannot be directly accessed via either public or privileged means, the desired effect can still be achieved by targeting an intermediating link or node so that the desired effect cascades from the first order effect.” An example of this is “conducting a DDOS attack on a critical link” leading to the target or “degradation through packet flooding” by assuming the “maximum data bus speed and a maximum input/output processor throughput on the target.” A ping flood attack can be “directed at a single IP address or broadcast to a whole Class B IP domain with thousands of recipients.”

The effectiveness of a cyber weapon corresponds to its ability to place a target into a particular state of operation. The target state “corresponds to the condition of the target with respect to a military objective” such as creating a root shell for privileged access. A typical cyberspace target state can typically be considered to operate in one of the following “five states relative to achieving a commander’s primary objective”:

- Unconfirmed: Unknown if there is an access path to target.

- Confirmed/Nominal: Access path to target established.

- Unprivileged access: Unprivileged access to target established.

- Privileged access/At risk: Privileged access to target established.

- Goal/Other condition: Target has been placed in the desired or other intermediate condition.

Using a real world example, the lexicon asks us to “consider the use of a ‘buffer overflow’ capability to achieve ‘root’ level (privileged) access on a computer operating system in order to disable an adversary’s computer program.” The use of a “buffer overflow creates an initial effect (access to unauthorized portion of memory) and, by including in the buffer overflow capability other carefully crafted code, it can also enable another effect (e.g. gaining root access) and place the target in a different state.” Whereas the previous state of the target was “nominal,” the new state of the target is “compromised.” If the system administrator has implemented “a mechanism to log and report all creations of a root shell,” the outcome can still create unintended consequences because the cyber weapon could be detected and then be susceptible to attribution or manipulation. With certain types of cyber weapons this sort of discovery or attribution could present serious problems, though with others it may prove to be of little use to the weapon’s discoverer. As cyber weapons only “deliver information or some other information-related effect to the target and not high explosive or high energy,” they can be used “as long as we have electrical power.”

U.S. Strategic Command Cyber Warfare Lexicon

Select a term from the following list to read the full definition. All definitions are taken from U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) Cyber Warfare Lexicon Version 1.7.6.

| cyberspace | cyber weapon vulnerability | kinetic |

cyberspace

(U//FOUO) cyberspace: a global domain within the information environment consisting of the interdependent network of information technology infrastructures, including the Internet, telecommunications networks, computer systems, and embedded processors and controllers. (from 12 May 2008 SECDEF memo)

[(U//FOUO) Previous version – cyberspace: A domain characterized by the use of electronics and the electromagnetic spectrum to store, modify, and exchange data via networked systems and associated physical infrastructures. (from NMS-CO)]

cyberspace operations (CO)

(U//FOUO) cyberspace operations (CO): All activities conducted in and through cyberspace in support of the military, intelligence, and business operations of the Department. (based on NMS-CO description)

(U//FOUO) cyberspace operations (CO): The employment of cyber capabilities where the primary purpose is to achieve military objectives or effects in or through cyberspace. Such operations include computer network operations and activities to operate and defend the global information grid. (from 29 Sep 2008 VJCS Memo, however it is inconsistent with NMS-CO and improperly limited)

cyber warfare (CW)

(U//FOUO) cyber warfare (CW): Creation of effects in and through cyberspace in support of a combatant commander’s military objectives, to ensure friendly forces freedom of action in cyberspace while denying adversaries these same freedoms. Composed of cyber attack (CA), cyber defense (CD), and cyber exploitation (CE).

cyber attack (CA)

(U//FOUO) cyber attack (CA): Cyber warfare actions intended to deny or manipulate information and/ or infrastructure in cyberspace. Cyber attack is considered a form of fires.

cyber defense (CD)

(U//FOUO) cyber defense (CD): Cyber warfare actions to protect, monitor, detect, analyze, and respond to any uses of cyberspace that deny friendly combat capability and unauthorized activity within the DOD global information grid (GIG).

cyber exploitation (CE)

(U//FOUO) cyber exploitation (CE): Cyber warfare enabling operations and intelligence collection activities to search for, collect data from, identify, and locate targets in cyberspace for threat recognition, targeting, planning, and conduct of future operations.

cyber warfare capability

(U//FOUO) cyber warfare capability: A capability (e.g. device, computer program, or technique), including any combination of software, firmware, and hardware, designed to create an effect in cyberspace, but that has not been weaponized. Not all cyber capabilities are weapons or potential weapons.

cyber weapon system

(U//FOUO) cyber weapon system: A combination of one or more weaponized offensive cyber capabilities with all related equipment, materials, services, personnel, and means of delivery and deployment (if applicable) required for self-sufficiency. (Note: adapted directly from JP 1-02 of weapon system.)

cyber weaponization

(U//FOUO) cyber weaponization: The process of taking an offensive cyber capability from development to operationally ready by incorporating control methods, test and evaluation, safeguards, security classification guidance, interface/ delivery method, certified and trained personnel, employment recorder, CONOP, TIP, life-cycle support, and launch platform.

cyber weapon characterization

(U//FOUO) cyber weapon characterization: The process of determining and documenting the effect producing mechanisms and assurance factors of cyber weapons. Characterization includes aspects of technical assurance evaluation, OT&E, risk/protection assessments, and other screening processes. Answers the question: “What do I need to know about this weapon before I can use it?” [Note: Cyber Weapon Characterization is one step in the Cyber Weaponization process.]

cyber weapon categorization

(U//FOUO) cyber weapon categorization: A binning of cyber weapon capabilities into categories, based on risk assessment and the release authority required for their use. Useful for answering the question: “Who can authorize use of this weapon?” Example categories might be:

• Category I- Combatant commander release

• Category II – Pre-approved for combatant commander use in specific OPLANs

• Category III- President/SECDEF release only

cyber weapon delivery mode

(U//FOUO) cyber weapon delivery mode: The method via which a cyber weapon (or a command to such a weapon) is delivered to the target. Delivery may be via direct implant or remote launch. Hardware cyber weapons often require direct implant. Remote launched cyber weapons and/or commands may be placed via wired and/or wireless paths.

cyber weapon flexibility

(U//FOUO) cyber weapon flexibility: The extent to which the cyber weapon’s design enables operator reconfiguration to account for changes in the target environment.

cyber weapon identification

(U//FOUO) cyber weapon identification: The manner in which a cyber weapon is represented for inventory control purposes, based on the weapon’s forensic attributes (e.g. for software: file name, file size, creation date, hash value, etc., for hardware: serial number, gram weight, stimulus response, x-ray image, unique markings, etc.).

cyber weapon vulnerability

(U//FOUO) cyber weapon vulnerability: An exploitable weakness inherent in the design of a cyber weapon. Weaknesses are often in one of the following risk areas:

- detectability risk – The risk that a weapon will be unable to elude discovery or suspicion of its existence. This includes the adverse illumination risk of hardware weapons.

- attribution risk – The risk that the discoverer of a weapon or its effect will be able to identify the source and/or originator of the attack or the source of the weapon used in the attack.

- co-optability risk – The risk that, once discovered, the weapon or its fires will be able to be recruited, used, or reused without authorization.

- security vulnerability risk – The risk that, once discovered, an unauthorized user could uncover a security vulnerability in the weapon that allows access to resources of the weapon or its launch platform. This includes the risk of an adversary establishing covert channels over a weapon’s C2 link.

- misuse risk – The risk that the weapon can be configured such that an authorized user could unintentionally use it improperly, insecurely, unsafely, etc.

- policy, law, & regulation (PLR) risk – The risk that the weapon could be configured such that an authorized user could intentionally use it in violation of existing policy, laws, and regulations.

access

(U) access: Sufficient level of exposure to or entry into a target to enable the intended effect.

collateral effect

(U) collateral effect: Unintentional or incidental effects, including injury or damage, to persons or objects that would not be lawful military targets in the circumstances ruling at the time.

deny

(U) deny: To attack by degrading, disrupting, or destroying access to or operation of a targeted function by a specified level for a specified time. Denial is concerned with preventing adversary use of resources.

- degrade(U) degrade: (a function of amount) To deny access to or operation of a targeted function to a level represented as a percentage of capacity. Desired level of degradation is normally specified.

- disrupt(U) disrupt: (a function of time) To completely but temporarily deny access to or operation of a targeted function for a period represented as a function of time. Disruption can be considered a special case of degradation where the degradation level selected is 100%.

- destroy(U) destroy: To permanently, completely, and irreparably deny access to, or operation of, a target. Destruction is the denial effect where time and level are both maximized.

dud

(U) dud: A munition that has not been armed or activated as intended or that failed to take an expected action after being armed or activated. (Note: adapted directly from JP 1-02 of dud.)

effects assessment (EA)

(U) effects assessment (EA): The timely and accurate evaluation of effects resulting from the application of lethal or non-lethal force against a military objective. Effect assessment can be applied to the employment of all types of weapon systems (air, ground, naval, special forces, and cyber weapon systems) throughout the range of military operations. Effects assessment is primarily an intelligence responsibility with required inputs and coordination from the operators. Effects assessment is composed of physical effect assessment, functional effect assessment, and target system assessment. Note: Battle Damage Assessment (BDA) is a specific type of effects assessment for damage effects. ” (This is a direct adaptation from the JP 1-02 definition of BDA.)

intended cyber effect

(U//FOUO) intended cyber effect: A sorting of cyber capabilities into broad operational categories based on the outcomes they were designed to create. These categories are used to guide capability selection decisions. Answers the question: “What kind of capability is this?” Specifically:

• denial – degrade, disrupt, or destroy access to, operation, quality of service, or availability of target resources, processes, and/or data.

• manipulation – manipulate, distort, or falsify trusted information on a target.

• command and control – provide operator control of deployed cyber capabilities.

• information/data collection – obtain targeting information about targets or target environments.

• access – establish unauthorized access to a target.

• enabling – provide resources or create conditions that support the use of other capabilities.

kinetic

(U) kinetic: Of or pertaining to a weapon that uses, or effects created by, forces of dynamic motion and/ or energy upon material bodies. Includes traditional explosive weapons/ effects as well as capabilities that can create kinetic RF effects, such as continuous wave jammers, lasers, directed energy, and pulsed RF weapons.

non-kinetic

(U) non-kinetic: Of or pertaining to a weapon that does not use, or effects not created by, forces of dynamic motion and/ or energy upon material bodies.

lethal

(U) lethal: Of or pertaining to a weapon or effect intended to cause death or permanent injuries to personnel.

non-lethal

(U) non-lethal: Of or pertaining to a weapon or effect not intended to cause death or permanent injuries to personnel. Nonlethal effects may be reversible and are not required to have zero probability of causing fatalities, permanent injuries, or destruction of property.

manipulate

(U//FOUO) manipulate: To attack by controlling or changing a target’s functions in a manner that supports the commander’s objectives; includes deception, decoying, conditioning, spoofing, falsification, etc. Manipulation is concerned with using an adversary’s resources for friendly purposes and is distinct from influence operations (e.g. PSYOP, etc.).

misfire

(U) misfire: The failure of a weapon to take its designed action; failure of a primer, propelling charge, transmitter, emitter, computer software, or other munitions component to properly function, wholly or in part. (Note: adapted directly from JP 1-02 of misfire.)

probability of effect (PE)

(U) probability of effect (PE): The chance of a specific functional or behavioral impact on a target given a weapon action.

target state

(U) target state: The condition of a target described with respect to a military objective or set of objectives.

targeted vulnerability

(U) targeted vulnerability: An exploitable weakness in the target required by a specific weapon.

- objective vulnerabilityobjective vulnerability: A vulnerability whose exploitation directly accomplishes part or all of an actual military objective.

- access vulnerabilityaccess vulnerability: A vulnerability whose exploitation allows access to an objective vulnerability.

weapon action

(U) weapon action: The effect-producing mechanisms or functions initiated by a weapon when triggered. The weapon actions of a kinetic weapon are blast, heat, fragmentation, etc. The weapon actions of a cyber attack weapon might be writing to a memory register or transmission of a radio frequency (RF) waveform.

weapon effect

(U) weapon effect: A direct or indirect objective (intended) outcome of a weapon action. In warfare, the actions of a weapon are intended to create effects, typically against the functional capabilities of a material target or to the behavior of individuals. Effect-based tasking is specified by a specific target scope, desired effect level, and start time and duration.

- direct effectdirect effect: An outcome that is created directly by the weapon’s action. Also known as a first order effect.

- indirect effectindirect effect: An outcome that cascades from one or more direct effects or other indirect effects of the weapon’s action. Also known as second, third, Nth order effects, etc.