The following report was released by the Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy in 1997.

Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy

- Senate Document 105-2

- 275 pages

- December 31, 1997

It is time for a new way of thinking about secrecy.

Secrecy is a form of government regulation. Americans are familiar with the tendency to overregulate in other areas. What is different with secrecy is that the public cannot know the extent or the content of the regulation.

Excessive secrecy has significant consequences for the national interest when, as a result, policymakers are not fully informed, government is not held accountable for its actions, and the public cannot engage in informed debate. This remains a dangerous world; some secrecy is vital to save lives, bring miscreants to justice, protect national security, and engage in effective diplomacy. Yet as Justice Potter Stewart noted in his opinion in the Pentagon Papers case, when everything is secret, nothing is secret. Even as billions of dollars are spent each year on government secrecy, the classification and personnel security systems have not always succeeded at their core task of protecting those secrets most critical to the national security. The classification system, for example, is used too often to deny the public an understanding of the policymaking process, rather than for the necessary protection of intelligence activities and other highly sensitive matters.

The classification and personnel security systems are no longer trusted by many inside and outside the Government. It is now almost routine for American officials of unquestioned loyalty to reveal classified information as part of ongoing policy disputes—with one camp “leaking” information in support of a particular view, or to the detriment of another—or in support of settled administration policy. In the process, this degrades public service by giving a huge advantage to the least scrupulous players.

The best way to ensure that secrecy is respected, and that the most important secrets remain secret, is for secrecy to be returned to its limited but necessary role. Secrets can be protected more effectively if secrecy is reduced overall.

Benefits can flow from moving information that no longer needs protection out of the classification system and, in appropriate cases, from not classifying at all. We live in an information-rich society, one in which more than ever before open sources—rather than covert means of collection—can provide the information necessary to permit well-informed decisions. Too often, our secrecy system proceeds as if this information revolution has not happened, imposing costs by compartmentalizing information and limiting access.

Greater openness permits more public understanding of the Government’s actions and also makes it more possible for the Government to respond to criticism and justify those actions. It makes free exchange of scientific information possible and encourages discoveries that foster economic growth. In addition, by allowing for a fuller understanding of the past, it provides opportunities to learn lessons from what has gone before—making it easier to resolve issues concerning the Government’s past actions and helping prepare for the future.

This does not mean that we believe the public should be privy to all government information. Certain types of information—for example, the identity of sources whose exposure would jeopardize human life, signals or imagery intelligence the loss of which would profoundly hinder the capability to collect critical data, or information that could aid terrorists—must be assiduously protected. There must be zero tolerance for permitting such information to be released through unauthorized means, including through deliberate or inadvertent leaks. But when the business of government requires secrecy, it should be employed in a manner that takes risks into account and attempts to control costs.

It is time to reexamine the long-standing tension between secrecy and openness, and develop a new way of thinking about government secrecy as we move into the next century. It is to that end that we direct our recommendations.

Ours is the first analysis authorized by statute of the workings of secrecy in the United States Government in 40 years, and only the second ever. We started our work with the knowledge that many commissions and reports on government secrecy have preceded us, with little impact on the problems we still see and on the new ones we have found.

In undertaking our mission to look at government secrecy, we have observed when the secrecy system works well, and when it does not. We have looked at the consequences of the lack of adequate protection. We have sought to diagnose the current system, and to identify what works and ways the system can work better. Above all, we have sought to understand how best to achieve both better protection and greater openness.

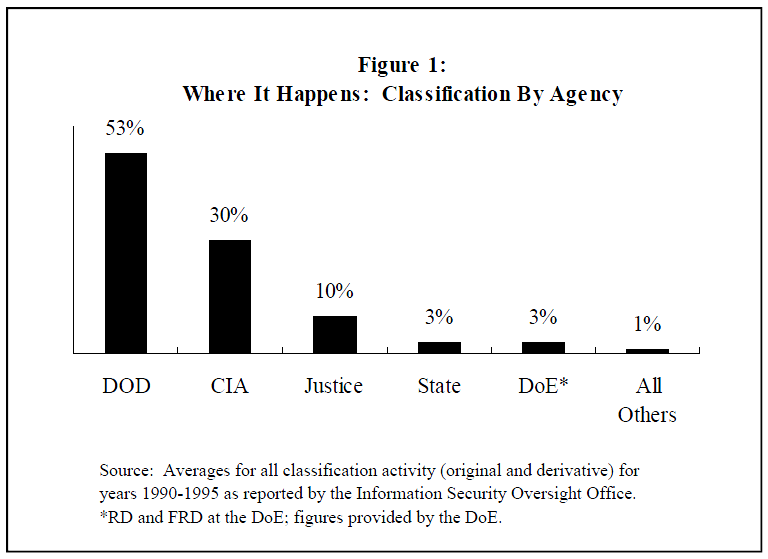

That the secrecy system that evolved and grew over the course of the 20th century would remain essentially unchanged and unexamined by the public was predictable. It is to be expected of a regulatory system essentially hidden from view. Some two million Federal officials, civil and military, and another one million persons in industry, have the ability to classify information. Categories of administrative markings also have proliferated over time, and the secrecy system has become ever more complex. The system will perpetuate itself absent outside intervention, and in doing so maintain not only its many positive features, but also those elements that are detrimental to both our democracy and our security.

It is time for legislation. There needs to be some check on the unrestrained discretion to create secrets. There needs to be an effective mode of declassification.

To improve the functioning of the secrecy system and the implementation of established rules, we recommend a statute that sets forth the principles for what may be

declared secret.Apart from aspects of nuclear energy subject to the Atomic Energy Act, secrets in the Federal Government are whatever anyone with a stamp decides to stamp secret. There is no statutory base and never has been; classification and declassification have been governed for nearly five decades by a series of executive orders, but none has created a stable and reliable system that ensures we protect well what needs protecting but nothing more. What has been consistently lacking is the discipline of a legal framework to clearly define and enforce the proper uses of secrecy. Such a system inevitably degrades.

We therefore propose the following as the framework for a statute that establishes the principles on which classification and declassification should be based:

Sec. 1 Information shall be classified only if there is a demonstrable need to protect the information in the interests of national security, with the goal of ensuring that classification is kept to an absolute minimum consistent with these interests.

Sec. 2 The President shall, as needed, establish procedures and structures for classification of information. Procedures and structures shall be established and resources allocated for declassification as a parallel program to classification. Details of these programs and any revisions to them shall be published in the Federal Register and subject to notice and comment procedures.

Sec. 3 In establishing the standards and categories to apply in determining whether information should be or remain classified, such standards and categories shall include consideration of the benefit from public disclosure of the information and weigh it against the need for initial or continued protection under the classification system. If there is significant doubt whether information requires protection, it shall not be classified.

Sec. 4 Information shall remain classified for no longer than ten years, unless the agency specifically recertifies that the particular information requires continued protection based on current risk assessments. All information shall be declassified after 30 years, unless it is shown that demonstrable harm to an individual or to ongoing government activities will result from release. Systematic declassification schedules shall be established. Agencies shall submit annual reports on their classification and declassification programs to the Congress.

Sec. 5 This statute shall not be construed as authority to withhold information from the Congress.

Sec. 6 There shall be established a National Declassification Center to coordinate, implement, and oversee the declassification policies and practices of the Federal Government. The Center shall report annually to the Congress and the President on its activities and on the status of declassification practices by all Federal agencies that use, hold, or create classified information.

…