The following guide to social engineering was released by the UK Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) on January 21, 2015.

An introduction to social engineering

- 10 pages

- January 2015

Social engineering is one of the most prolific and effective means of gaining access to secure systems and obtaining sensitive information, yet requires minimal technical knowledge. Attacks vary from bulk phishing emails with little sophistication through to highly targeted, multi-layered attacks which use a range of social engineering techniques. Social engineering works by manipulating normal human behavioural traits and as such there are only limited technical solutions to guard against it. As a result, the best defence is to educate users on the techniques used by social engineers, and raising awareness as to how both humans and computer systems can be manipulated to create a false level of trust. This can be complemented by an organisational attitude towards security that promotes the sharing of concerns, enforces information security rules and supports users for adhering to them. Even so, a determined attacker with sufficient skill, resources and ultimately, luck, will be able to retrieve the information they are seeking. For this reason, organisations and individuals should have measures in place to respond to, and recover from, a successful attack.

Phishing

The most prolific form of social engineering is phishing, accounting for an estimated 77% of all social-based attacks with over 37 million users reporting phishing attacks in 2013. Phishing is the fraudulent attempt to steal personal or sensitive information by masquerading as a well-known or trusted contact. Whilst email phishing is the most common, phishing attacks can also be conducted via phone calls, text messages and fax, as well as other methods of communication, including social media.

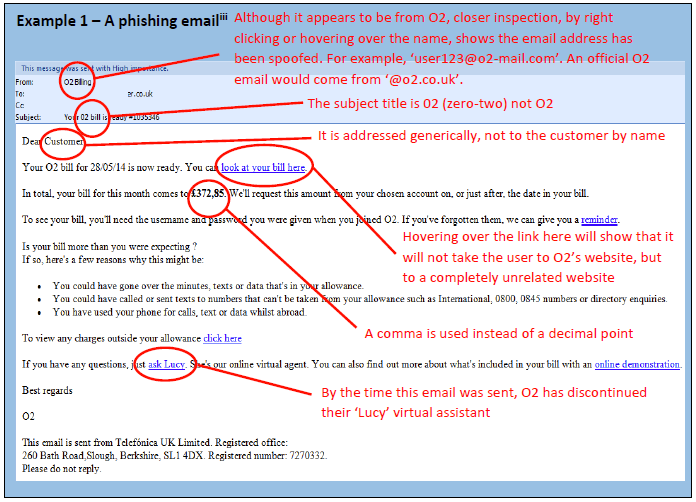

A large amount of wide scale email phishing attacks remain unsophisticated and will be recognised by most (although not all) computer users as illegitimate. However, email phishing is becoming increasingly sophisticated and attackers will use a variety of techniques to either make the email appear legitimate or to lure the victim into acting before thinking. Attackers may disguise the address the email is sent from so that it appears to be from a well-known organisation and common ones include banks, utility companies, couriers, recruitment agencies and government. Better designed phishing emails will actually appear to be very similar imitations of legitimate emails from these organisations (see example 1). Another common technique is to make use of major news events by posing as having new information on the event, or asking the recipient to take action (donate money, sign a petition, etc.) in relation to the event.

Despite increasing competency in wide scale campaigns, there are still indicators that frequently appear in phishing emails:

- Messages are unsolicited (i.e. the victim did nothing to initiate the action)

- Messages are vague, not addressed to the target by name and beyond purporting to be from a known organisation, contain little other specific or accurate information to build trust

- May be from an organisation with which the target has no dealing with

- Contain poor spelling and grammar, typos or use odd phrases; whilst this is becoming less common as attackers are becoming more proficient, mistakes are still made

- Are too good to be true or make unrealistic threats, often with a sense of urgency

- Are sent from an email address that, whilst perhaps similar, does not match ones used officially by an organisation

- Contain incorrect or poor versions of an organisation’s logo, and may contain web links to sites that, whilst perhaps similar, are not ones used by that organisation

Phishing emails often ask the user to follow a link to a website or open an attachment. Some may ask the user to reply to the email, after which they will be engaged in an exchange of messages to elicit confidential information. When asked to click on a link, it may be designed so that the text the victim clicks on appears to be for a known website, but the link takes them to a completely different website (a technique known as obfuscation). At the website, the victim will then be asked to enter confidential information or may unknowingly download a file which will subsequently infect their machine with malware. Likewise, any attachment on a phishing email is likely to contain malware.

…

Watering hole attacks

Watering hole attacks, similar to baiting, use trusted websites to infect victim’s computers. They are typically more sophisticated than most other social engineering techniques as they also require some technical knowledge. A watering hole attack works by compromise a trusted third party website to deliver malicious code against the intended victim’s computer. As with other targeted social engineering attacks, the attacker will research their intended victim(s) and identify one or more trusted websites that they are likely to access. This may be a supplier’s website, an industry journal, think tank or some other website that the attacker has identified as of interest to the intended victim. Having identified a suitable website (or websites), the attacker will seek out vulnerabilities within the server that hosts the website, and having found one, insert code that will enable malware to be downloaded, sometimes with little or no interaction from the victim (known as a ‘drive-by’ attack).

…

Attacking on multiple fronts

A determined attacker may adopt a multi-layered approach along with additional techniques to increase their target’s trust, or confusion, in order to maximise the chance of success. Whilst somewhat indiscriminate, an attacker could begin dialling random numbers within an organisation claiming to be IT support (potentially using a real name from the IT support department gleaned from social media) until they eventually find a victim that does have an IT issue. In their attempt to solve the problem, they will trick the user into giving them login, password or other information that will be useful in compromising their computer. Alternatively, the attacker may pretend to be an executive, urgently demanding to be sent an important (and sensitive) document to their personal email address as they cannot access their work account. In both cases, the victim is put under pressure to do something they should know they should not do: they do not want to question someone who knows more than them (IT support), or who is senior to them (the executive), and refusal to comply could get them in trouble. Some attackers may be even more creative (see example 4).