Tactical Level Commander and Staff Toolkit

Tactical Level Commander and Staff Toolkit

- 402 pages

- July 2010

Due to readiness requirements, military personnel are capable of rapid response to a broad spectrum of emergencies. Because military personnel and their associated equipment can often be effectively employed in civil support operations, civil authorities continue to call upon the military for assistance.

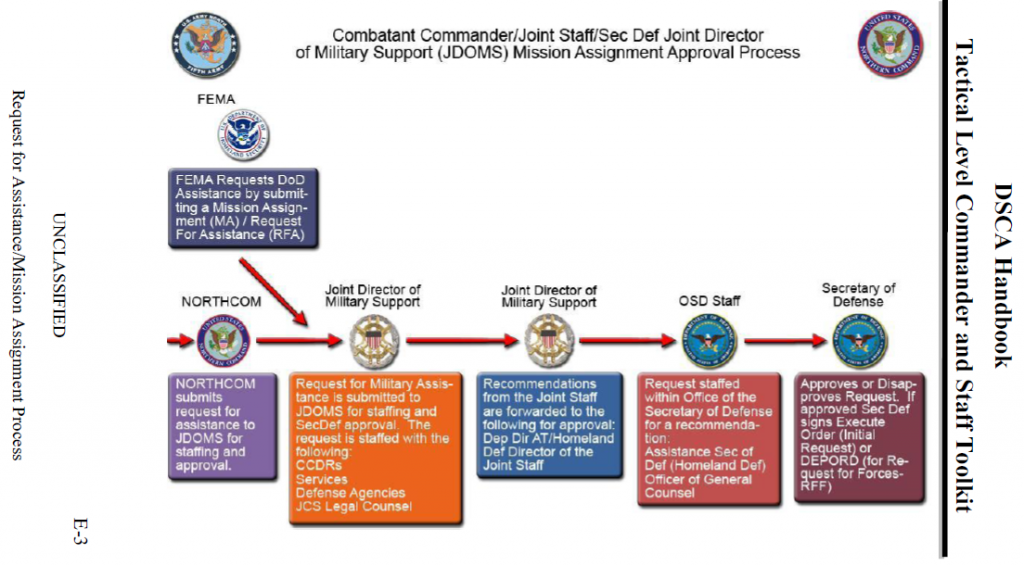

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), under the direction of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), is the Primary Agency (PA) in the federal response to natural disasters. DoD resources, in coordination with FEMA, may be requested to augment local, state, and federal capabilities in assisting with a state-led response. An exception is wildland firefighting, in which case the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) is the PA.

This handbook has been developed primarily to support DSCA operations in the Area of Responsibility (AOR) of United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM), including the 48 contiguous states, Alaska, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, and the AOR of United States Pacific Command (USPACOM) including Hawaii, Guam, and American Samoa. Specific references to USNORTHCOM in this document are not intended to exclude USPACOM.

…

Liaison Officer Toolkit

Liaison Officer Toolkit

- 168 pages

- July 2010

2.1 Military Law Enforcement in DSCA

The most legally sensitive function in DSCA is Military Law Enforcement. Consequently, to prevent violations of the law, all military personnel should be educated on MLE. The main legal obstacle to the use of the military for law enforcement is the Posse Comitatus Act (PCA), discussed briefly in Section 2.3.1 of this chapter. (For more detail on PCA, see Annex A.) The PCA affects National Guard (either in State Active Duty (SAD) or Title 32) and federal forces (Title 10) differently. Thus, it is very important to understand the status of military personnel prior to mission assignment.

2.1.1 Individual Protection/Force Protection

Military forces have the right and responsibility to protect themselves and their assets at all times. State military justice laws, for Title 32 and SAD, and the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) for Title 10 and are always in effect for military personnel.

2.1.2 Physical Security/Critical Infrastructure Protection

Most physical security and critical infrastructure protection activities are performed by non-military organizations, often involving Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with the local civilian law enforcement authorities. The most likely use of the military is through the local National Guard forces. However, there is a process to receive federal aid.

The Critical Infrastructure and Key Resources (CIKR) Support Annex to the National Response Framework (NRF) dated January 2008 covers the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)/ Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) plan for addressing critical infrastructure. The annex can be accessed at http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/NIPP_Plan.pdf

CIKR-related preparedness, protection, response, and recovery activities operate within a framework of mutual aid and assistance. Incident-related requirements can be addressed through direct actions by owners and operators or with government assistance provided by federal, state, tribal, or local authorities in certain specific circumstances.

Under the Stafford Act, disaster assistance programs generally offer support for incident-related repair, replacement, or emergency protective services needed for infrastructure owned and operated by government entities. Stafford Act principles permit consideration of private-sector requests for assistance, but the application of these legal principles does not guarantee that needs or requests from private-sector entities will be met in all cases. A private-sector CIKR owner or operator may receive direct or indirect assistance from federal government sources when the need:

• Exceeds capabilities of the private sector and relevant state, tribal, and local governments

• Relates to immediate threat to life and property

• Is critical to disaster response or community safety

• Relates to essential federal recovery measures2.1.3 Traffic Direction/Control

The PCA impacts all federal forces by prohibiting them from performing any law enforcement actions, including directing traffic. Consequently, federal military forces may not direct traffic in a civilian jurisdiction unless it is to help military vehicles/convoys that need to arrive at a destination quickly in order to perform an urgent mission, and to move through an area unimpeded. In these unique situations, federal military forces rely on the Military Purpose Doctrine exception to the PCA. The National Guard may direct traffic, in accordance with state law. This may seem like a trivial point, but it can cause unnecessary legal problems if not handled correctly.

2.1.4 Civil Disturbance

All DSCA operations have the potential for civil disturbance. How civil disturbance is handled will depend upon the specifics of the incident and must have Presidential approval. (For more details see Section 2.1.4.2). However, federal military commanders may exercise emergency authority in civil disturbance situations as described below. In these circumstances, federal military commanders will use all available means to seek specific authorization from the President through their chain-of-command while operating under their emergency authority.

Emergency authority can be used in only two circumstances:1. The use of federal military forces is necessary to prevent loss of life or wanton destruction of property, or to restore governmental functioning and public order. Under these conditions, emergency authority applies when sudden and unexpected civil disturbances occur, if duly constituted local authorities are unable to control the situation and circumstances preclude obtaining prior authorization by the President.

2. Duly constituted federal, state, or local authorities are unable or decline to provide adequate protection for federal property or federal governmental functions located in the area of the civil disturbance and circumstances preclude obtaining prior authorization by the President. Federal action, including the use of federal military forces, is authorized when necessary to protect the federal property or functions.

Violent crowd actions can be extremely destructive. The only limits to violent crowd tactics are the attitude and ingenuity of crowd members, training of their leaders, and the materials available are. Crowd or mob members may commit violent acts with crude, homemade weapons or anything else that is available. If violence is planned, crowd members may conceal makeshift weapons or tools for vandalism. Rioters can be expected to vent their emotions on individuals, troop formations, and equipment. They may throw rotten fruits and vegetables, rocks, bricks, bottles, or improvised bombs. They may direct dangerous objects (vehicles, carts, barrels, or liquids) at troops located on or at the bottom of a slope. They may drive vehicles toward troops to scatter formation and jump out of vehicles before reaching roadblocks and barricades. Rioters may set fire to buildings or vehicles to block the advance of the formation, create confusion and diversion, and destroy property. Types of riots include: Organized riots: Leaders organize the population into quasi-military groups capable of developing plans and tactics for riots and disorders. Riots can be instigated for:

Theft of property/supplies—leaders organize a riot as a way to disrupt security surrounding logistics control points, with the objective of seizing guarded property. Political purposes—riots are often organized for propaganda or to embarrass the government. Grievance protests—a grievance protest can be organized as a riot. Under normal circumstances, this type of riot is not extremely violent in nature. It may turn violent when leaders try to exploit the successes of the riot or the weaknesses of the security force. Unorganized riots: Unorganized riots are spontaneous, although they can be exploited and diverted by leaders into different types of riots. They are usually indicative of extreme frustration and fear. Under determined leadership, the pattern of these gatherings can change to an organized riot. Once a riot begins, it can spread to other areas and become entrenched in several different key locations.

2.1.4.2 Federal Intervention and Aid

Under the Constitution of the United States and the Insurrection Act, the President is empowered to direct federal intervention in civil disturbances to:

• Respond to state requests for aid in restoring order

• Enforce the laws of the United States

• Protect the civil rights of citizens

• Protect federal property and functionsThe Constitution of the United States and federal statutes authorize the President to direct the use of armed federal troops within the 54 states and territories and their political subdivisions. The President is also empowered to federalize the National Guard of any state to suppress rebellion and enforce federal laws.