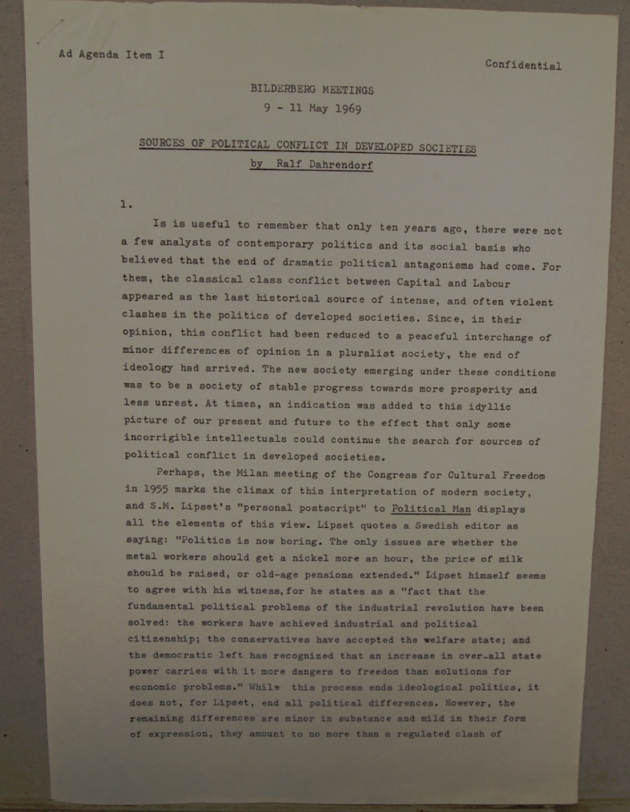

It is useful to remember that only ten years ago, there were not a few analysts of contemporary politics and its social basis who believed that the end of dramatic political antagonisms had cone. For then, the classical class conflict between Capital and Labour appeared as the last historical source of intense, and often violent clashes in the politics of developed societies. Since, in their opinion, this conflict had been reduced to a peaceful interchange of minor differences of opinion in a pluralist society, the end of ideology had arrived. The new society emerging under these conditions was to be a society of stable progress towards more prosperity and less unrest. At tines, an indication was added to this idyllic picture or our present and future to the effect that only some incorrigible intellectuals could continue the search for sources of political conflict in developed societies.

Perhaps, the Milan meeting of the Congress for Cultural Freedom in 1955 marks the climax of this interpretation of modern society, and S.M. Lipset’s “personal postscript” to Political Man displays all the elements of this view. Lipset quotes a Swedish editor as saying: “Politics now boring. The only issues are whether the metal workers should get a nickel more an hour, the price of milk should be raised, or old—age pensions extended.” Lipset himself seems to agree with his witness, for he states as a “fact that the fundamental political problems of the industrial revolution have been solved: the workers have achieved industrial and political citizenship; the conservatives have accepted the welfare state; and the democratic left has recognized that an increase in over-all state power carries with it more dangers to freedom than solutions for economic problems.” While this process ends ideological politics, it does not, for Lipeet, end all political differences. However, the remaining differences are minor in substance and mild in their fora or expression, they amount to no more than a regulated clash of groups.