Center for Army Lessons Learned Handbook

- 99 pages

- For Official Use Only

- April 2011

- 8 MB

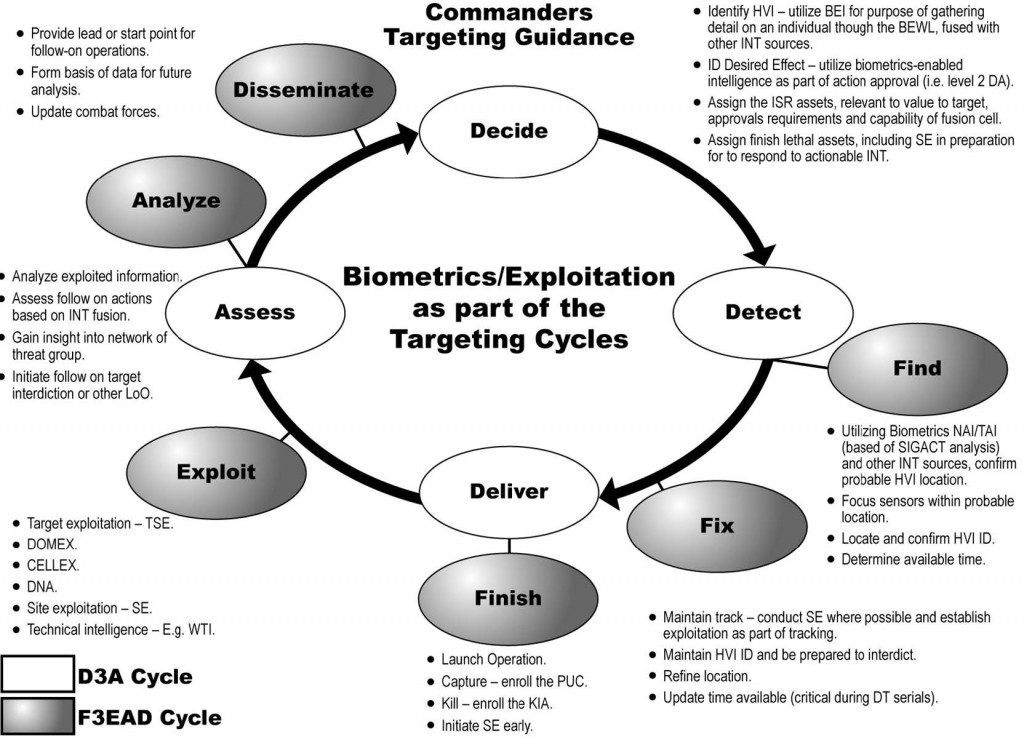

Biometrics capabilities on the tactical battlefield enable a wide variety of defensive and offensive operations. Biometrics help ensure enemy personnel, criminals, and other undesirable elements are not allowed access to our facilities, hired to provide services, or awarded contracts. Biometrics is used to vet members of the Afghan government and military with whom our forces interact. Unfortunately, biometrics capabilities we put in the hands of Soldiers, Marines, Sailors, and Airmen — and that we ask unit commanders to employ — are relatively recent additions to the list of capabilities our military employs on the battlefield today.

In most cases, biometrics systems are not part of any unit’s modified table of organization and equipment, and yet are used in combat by personnel who do not have a formal skill identifier. There is a lack of formal doctrine for employing biometrics capabilities by units and no recognized task, conditions, and standards that can be instituted to ensure these capabilities are employed consistently to maximum effect. Additionally, the vast majority of training conducted in biometrics is focused on equipment operation and not enough emphasis is given to leader training. The result is that units often struggle to employ biometrics capabilities effectively or to maximize its effects across the operational spectrum.

Within Afghanistan, Task Force Biometrics currently deploys personnel at the brigade combat team (BCT) and regional command (RC) levels to work with unit commanders and their staffs to help integrate biometrics more effectively into mission planning and execution. Task Force Biometrics is ready to provide additional training to any member who collects biometrics — including International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) partners. Task Force Biometrics is also the lead organization for all biometrics-enabled intelligence (BEI) actions in theater and currently maintains BEI personnel at the BCT and RC levels to assist intelligence staffs and provide focused input into the theater biometrics enabled watch list (BEWL). BEI personnel at Task Force Biometrics, in concert with continental U.S. intelligence agencies and organizations, has developed a wide variety of products that fuse biometrics information with forensics, terrain analysis, and other forms of intelligence to provide commanders information that helps better direct counterinsurgency (COIN) operations.

This handbook is intended to help bridge the doctrinal gap within the Department of Defense and to provide unit commanders with useful information to effectively employ biometric capabilities in the unique environment and operational conditions of Afghanistan. It is not intended to replace current or future ISAF guidance on the employment of biometrics; its aim is simply to generate a better understanding of how to integrate biometrics into operations before units deploy to combat.

…

All units will have access to both table top and hand-held biometrics collection equipment like the Biometrics Automated Toolset (BAT) and Handheld Interagency Identity Detection Equipment (HIIDE). This equipment helps units conduct biometrics collection for a wide range of missions across the spectrum of operations. Lessons from theater indicate it is vital for commanders to ensure their personnel are adequately trained to effectively operate the equipment. Just as an infantry commander would not rotate duties of manning a machine gun at random, operation of biometric equipment should be a dedicated mission for a designated group of service members. Evidence in theater indicates that dedicated biometric enrollers increase the level of proficiency and enable more thorough collections. Complete collections create greater chances of finding persons of interest (POIs). Biometrics collection is a nonlethal weapon system feeding operational synchronization metrics.

The results of collection activities are exploited using theater- and national-level biometric databases. However, poorly executed collections may result in an insurgent gaining access to our facilities or personnel in Afghanistan. For example, if a service member only collects six fingerprints using the HIIDE, one of the four missing prints may be the one extracted from a piece of black tape used to construct an IED. Getting the collection right the first time is a critical component to help biometrics-enabled intelligence (BEI) analysts link POIs to an event. Most importantly, quality collection requires leader involvement, training, and daily vigilance.

Simply stated, collecting fingerprints with biometric collection devices has led to the apprehension of bomb makers and emplacers. Photographing individuals in a given area will assist in development of target packages and build a knowledge base of the populace. Collecting irises provides positive identification of an encountered person, greatly improving force protection at all facilities. Biometrics (e.g., fingerprints, iris images, face photos) will positively identify an encountered person and unveil terrorist or criminal activities regardless of paper documents, disguises, or aliases.

Biometrics and Counterinsurgency

Counterinsurgencies have traditionally succeeded when insurgents were physically separated from the populace. In the past, such separation required relocation into protected areas. Today, with biometrics on the battlefield, we can separate insurgents from the populace without moving anyone. Afghan elders or maliks are village leaders who are generally interested in protecting their people. When it is demonstrated how biometrics can separate insurgents from their people and make them safer, they will generally be supportive of enrollments (Figure 1-1). By conducting population management patrols and performing quality enrollments, commanders will know who belongs in a particular area of operation, what they do, and exactly who they are.

The probability of identifying those who are tied to criminal or insurgent activity increases as the biometric database grows. Collecting biographic and contextual information builds a knowledge base of who is in the operational area; however, a biometrics collection device stored in a Conex storage container will not identify a single individual on the biometrics enabled watch list (BEWL). Afghanistan becomes more secure as more individuals involved in nefarious activities are identified and removed from the battlefield. As a result, coalition forces and the Afghan population are safer, and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA) achieves legitimacy while the insurgents simultaneously become more isolated.

Relationship Between Biometrics and Forensics

The relationship between biometrics and forensics can be explained when you understand their definitions. Biometrics is the measuring and analysis of physical human attributes and forensics is scientific tests or techniques used in connection with the detection of crime or event. The military term “battlefield forensics” is defined as multidisciplinary, scientific processes, capabilities, and technologies used to establish facts that uniquely identify, associate, and link people, places, things, intentions, activities, organizations, and events to each other in support of battlefield activities such as military intelligence, targeting, and identity superiority operations.

Biometric collection devices used by U.S. forces typically collect fingerprints, iris images, and facial images and stores this data into local and national databases. This data then can be searched upon and compared to other collected biometrics and is used primarily for identification or verification of an individual. Fingerprints and DNA are examples of biometrics and can be collected directly from a detained, willing, or deceased individual. U.S. forces use buccal swabs to capture the buccal cells that line the mouth (Figure 1-2) and digital scanners or standard ink cards to capture fingerprints (Figure 1-3).

Using forensic processes such as lifting a latent fingerprint or collecting DNA from materials or evidence found through the examination of IED components after an explosion can result in identifying biometrics. Through exploitation of these types of biometrics, individual identification and possible attribution can be made. Forensics can also be used to conduct chemical or materials analysis of IED components to determine their possible association with other events and individuals and to establish the facts surrounding an incident.

Specific battlefield forensics are covered in the handbook Forensics for Commanders, published by the Office of the Provost Marshal General, and there are a wide variety of forensic activities occurring in Afghanistan today. Many of these activities are conducted specifically for the counter IED effort by individuals from weapons intelligence teams and other related organizations. In addition, units often collect forensics materials during site exploitation missions. IED-related materials are normally exploited by Combined Explosives Exploitation Cell labs, while non-IED materials are handled by the joint expeditionary forensics facility labs. The bottom line is that captured enemy materials and energetic fragments/components must be exploited as quickly as possible and the forensically collected biometrics data transmitted to the authoritative database — Automated Biometrics Identification System (ABIS) (see Figure 1-4).

In law enforcement, forensic evidence is analyzed to answer questions associated with a case. On the battlefield, forensic materials are analyzed to answer questions associated with intelligence requirements. In a criminal setting, forensic scientists must explain their conclusions to detectives, lawyers, and juries. In a battlefield setting, forensic intelligence analysts must explain their conclusions to commanders, who make decisions about committing forces and conducting specific actions in a combat environment. Forensics on the battlefield in Afghanistan are being used at an increasing rate by the Afghan criminal justice system, and convictions are now occurring in the Afghan courts based solely on biometric evidence. Figure 1-5 depicts the enrollment and exploitation linkage enabled through forensics, analysis, and communication systems.

Biometrics Process

The biometrics process involves collection and transmission of biometrics information to an authoritative database for storage, matching, and sharing to develop the assurance of an individual’s identity. It is closely linked to the intelligence process, as the latter determines the significance of the identity revealed by the match (Figure 1-6). The intelligence process is also responsible for the development of a key product used to support tactical biometrics operations — the BEWL. The BEWL, commonly referred to as “the watch list,” is a collection of individuals whose biometrics have been collected and determined by BEI analysts to be threats, potential threats, or who simply merit tracking.

When properly loaded onto a biometrics collection device, the BEWL allows for instantaneous feedback on biometrics collections without the need for real-time communications to the authoritative biometrics database. If the BEWL is not updated on the device though, units may lose their only opportunities to detain a POI. For example, a service member in Helmand province may collect the biometrics of an unidentified male encountered on a combat patrol. If that individual is on the BEWL and the Soldier’s HIIDE (Figure 1-7) is properly updated, the Soldier will immediately get the appropriate feedback on what actions to take based on the level of watch list that person is categorized. If the HIIDE has not been properly updated, the unit will have no reason to detain the person of interest and will have lost perhaps its only opportunity to do so.

If no watch list match is made during a collection, the biometrics data and associated contextual information required for enrollment will be transmitted back to the Department of Defense (DOD) ABIS for matching against all other collected biometrics. If a match is made there, that information is sent to the National Ground Intelligence Center (NGIC) in Charlottesville, VA, which generates a biometrics intelligence analysis report (BIAR) detailing the actions and potential threat of an individual. NGIC then contacts Task Force (TF) Biometrics in Afghanistan which, in turn, contacts the appropriate operational environment owner to provide updated intelligence on the POI. This process can take from a matter of minutes for special operations forces to several days for conventional units if the match is made against a latent fingerprint. Even if no match is made, the biometrics and enrollment information are stored for use in future cases and to enable the BEI process, emphasizing that all collections are important.

Once BEI analysts fuse biometric enrollments, forensic evidence, and all other forms of intelligence they develop the BEWL in cooperation with numerous other intelligence, agencies and organizations. In Afghanistan, regular updates are done by TF Biometrics and posted on secure sites to authorized users. For example, if a watch list level 1 (WL1) or watch list level 2 (WL2) individual is added during the week, TF Biometrics will post snap updates to ensure units minimize the chances of inadvertently releasing a key person of interest. Figure 1-8 graphically depicts the BEWL development, enrollment, and exploitation linkage enabled through forensics, analysis, and communication systems.

•• Twenty-nine BEI analysts are the focal point for the BEWL located throughout the operational environment, including presence at each brigade combat team (BCT).

•• Analysts combine biometric modalities, forensic exploitation, and allsource intelligence to develop the BEWL.

•• TF Biometrics publishes the BEWL every Sunday; snap updates occur as needed for WL1 or WL2 individuals.

•• Units can specifically request to add/delete specific persons on BEWL. Approval for additions are made at the BEI analyst level; deletions require approval from the TF Biometrics director.Biometrics Value Chain

The Biometrics value chain (Figure 1-9) outlines the biometric process and how each part builds on the next, leading to mission success. The impact of fingerprint collections, both forensically and with biometrics devices, ranges from the battlefield to the U.S. and other areas where we encounter terrorists or insurgents. Through DOD ABIS, fingerprints are matched and shared with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). With over 90 million fingerprint entries collected, DHS has the largest database for use in the US-VISIT program, which tracks the entry and exit of foreign visitors by using electronically scanned fingerprints and photographs. The FBI has the largest database of criminal enrollments with over 55 million entries. Through international collaboration, access to other countries’ criminal fingerprint enrollments is used to match against collected fingerprints to ensure criminals do not go undetected.

…