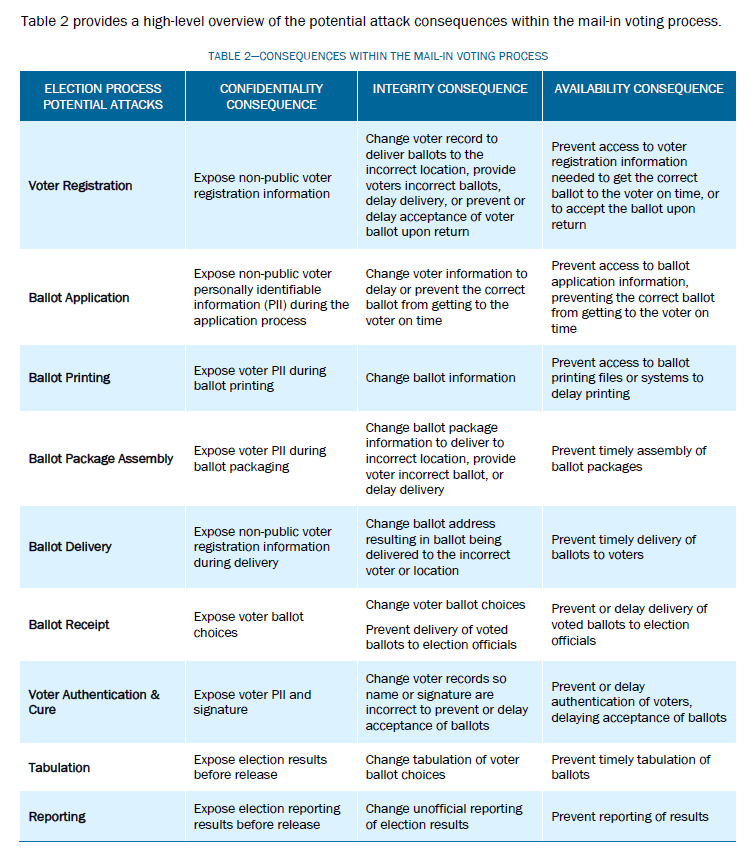

All forms of voting – in this case mail-in voting – bring a variety of cyber and infrastructure risks. Risks to mail-in voting can be managed through various policies, procedures, and controls.

The outbound and inbound processing of mail-in ballots introduces additional infrastructure and technology, which increases the potential scalability of cyber attacks. Implementation of mail-in voting infrastructure and processes within a compressed timeline may also introduce new risk. To address this risk, election officials should focus on cyber risk management activities, including access controls and authentication best practices when implementing expanded mail-in voting.

Integrity attacks on voter registration data and systems represent a comparatively higher risk in a mail-in voting environment when compared to an in-person voting environment. This is because the voter is not present at the time of casting the ballot and cannot help to answer questions regarding their eligibility or identity verification.

Operational risk management responsibility differs with mail-in voting and in-person voting processes. For mail-in voting, some of the risk under the control of election officials during in-person voting shifts to outside entities, such as ballot printers, mail processing facilities, and the United States Postal Service (USPS).

Physical access at election offices and warehouses represents a risk in a mail-in voting environment. Completed ballots are returned to the election office and must be securely stored for days or weeks before processing through voter authentication and tabulation processes. Managing risks to these processes requires implementing secure procedures for storage, access controls, and chain of custody, such as ballot accounting.

Inbound mail-in ballot processes and tabulation take longer than in-person processing, causing tabulation of results to occur more slowly and resulting in more ballots to tabulate following election night. Media, candidates, and voters should expect less comprehensive results on election night, which creates additional risk of electoral uncertainty and confidence in results.

Disinformation risk to mail-in voting infrastructure and processes is similar to that of in-person voting while utilizing different content. Threat actors may leverage limited understanding regarding mail-in voting processes to mislead and confuse the public.

…

Election infrastructure includes a diverse set of systems, networks, and processes. Mail-in voting is a method of administering elections. When voting by mail, authorized voters receive a ballot in the mail, either automatically or after the application process. In most implementations, the voter marks the ballot, puts the ballot in an envelope, signs an affidavit, and returns the package via mail or by dropping off at a ballot drop box or other designated location.

Currently, five states (Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington) automatically send every registered voter a ballot by mail. At least 21 other states have laws that allow at least some elections to be conducted by mail. In addition to the five states that send every voter a ballot, five states (Arizona, California, Montana, Nevada, and New Jersey) and the District of Columbia (D.C.) allow a voter to apply to receive a mail-in ballot permanently, so that voters do not have to apply each election.1 Currently, 34 states and D.C. allow any registered voter to request a mail-in ballot. There are 16 states that require voters to have an excuse such as temporary absence from the voting district, illness, or disability or require voters to be of a certain age (typically 65+) to be eligible to receive a ballot by mail. Some states are recognizing COVID-19 as a valid excuse.

Although they perform similar functions, mail-in voting processes and infrastructure vary from state to state and often differ even between counties, parishes, towns, or cities within a state or territory. While each state manages and conducts mail-in elections differently based on state and local legal requirements, common risks and mitigations exist across states and implementations.

…

Voter registration and mail ballot application processing collects data used to determine voter eligibility, the type of ballot a voter receives, the location or address for mailing the ballot to the voter, and whether election officials can accept the ballot. Either an integrity attack or an availability attack on a voter registration system could result in a voter not being able to cast a ballot or a voter’s ballot not being counted. Integrity attacks on voter registration data and systems represents a comparatively higher risk in a mail-in voting environment than an in-person voting environment. This is because the voter is not present at the time of casting the ballot and cannot help to resolve questions regarding eligibility or verification. Mail-in voters whose registration records are altered or deleted in an integrity attack do not have the opportunity to be issued a provisional ballot, which are available to in-person voters.

- An integrity attack that removed a voter from the voter registration, permanent mail, or absentee ballot request list could result in the voter not receiving a ballot, unless the voter proactively followed up to re-register, re-apply, or if the election official received the ballot as undeliverable and contacted the voter. The impact is that a voter may not receive a ballot or receipt of a ballot may be delayed, resulting in a jurisdiction potentially not accepting a voted ballot. The voter would still possess the ability to vote in person provisionally.

- An integrity attack on a voter’s name could result in the voter receiving a ballot package that is not addressed to the proper individual. If there was an integrity attack on a voter’s identifying information (i.e., date of birth [DOB], driver’s license number [DL], last four digits of Social Security number [SSN], etc.), the voter’s proof of ID, where required, would not match the voter’s record. The voter would either need to inform the election official and update his or her voter record (assuming that the voter registration deadline has not passed), or risk having their voted ballot rejected upon receipt.

- An integrity attack on a voter’s ballot mailing address may result in the voter not receiving a ballot, unless the voter proactively updated his or her registration with the correct address, or the election official received the ballot as undeliverable and contacted the voter. This assumes that the voter registration or ballot application deadline has not passed, allowing the voter to update his or her information. The impact is that a voter may not receive a ballot, or receipt of a ballot is delayed.

- An integrity attack on a voter’s signature on file could result in the voter having the ballot package rejected and their ballot uncounted. If the state is one of the 19 that requires a voter to receive notification when there is a discrepancy with their signature or the signature on the return ballot envelope is missing (a.k.a. “cure process”), the voter may have an opportunity to correct the situation by being notified that the ballot was rejected and taking action to resolve the issue. This can be done by an election official notifying the voter or a voter checking a ballot tracking system, if available.

- An availability attack on the voter registration database or specific information, such as a list of mail voters, voter names, or addresses could result in the delay of voters receiving their ballots, and further impact voters’ ability to return ballots on time to ensure they are counted. In most states, a ballot may be returned in person, in which case the impact of an availability attack may only affect the outbound process providing a measure of resilience.

…