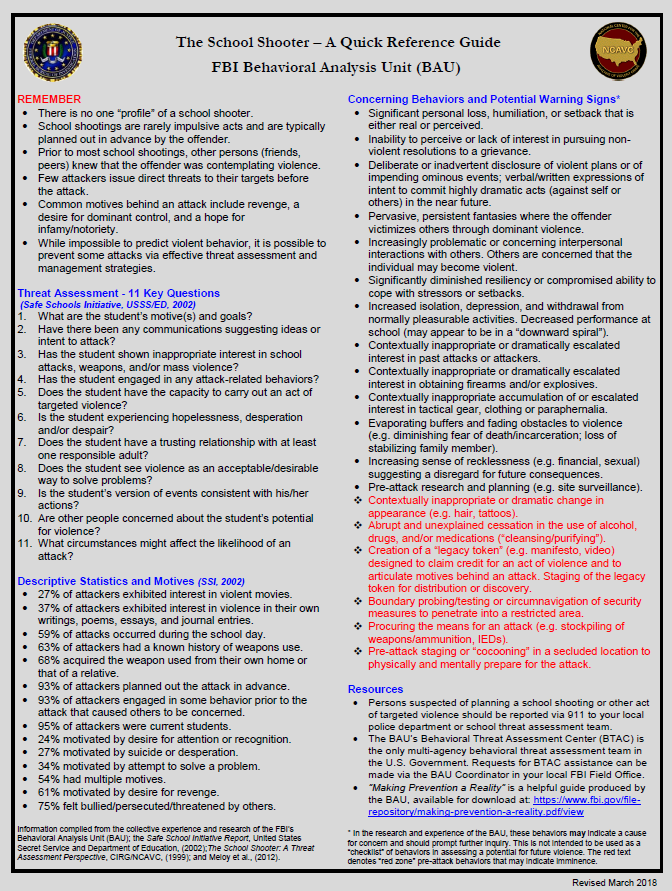

REMEMBER

- There is no one “profile” of a school shooter.

- School shootings are rarely impulsive acts and are typically planned out in advance by the offender.

- Prior to most school shootings, other persons (friends, peers) knew that the offender was contemplating violence.

- Few attackers issue direct threats to their targets before the attack.

- Common motives behind an attack include revenge, a desire for dominant control, and a hope for infamy/notoriety.

- While impossible to predict violent behavior, it is possible to prevent some attacks via effective threat assessment and management strategies.

Threat Assessment – 11 Key Questions

(Safe Schools Initiative, USSS/ED, 2002)

1. What are the student’s motive(s) and goals?

2. Have there been any communications suggesting ideas or intent to attack?

3. Has the student shown inappropriate interest in school attacks, weapons, and/or mass violence?

4. Has the student engaged in any attack-related behaviors?

5. Does the student have the capacity to carry out an act of targeted violence?

6. Is the student experiencing hopelessness, desperation and/or despair?

7. Does the student have a trusting relationship with at least one responsible adult?

8. Does the student see violence as an acceptable/desirable way to solve problems?

9. Is the student’s version of events consistent with his/her actions?

10. Are other people concerned about the student’s potential for violence?

11. What circumstances might affect the likelihood of an attack?

Descriptive Statistics and Motives (SSI, 2002)

- 27% of attackers exhibited interest in violent movies.

- 37% of attackers exhibited interest in violence in their own writings, poems, essays, and journal entries.

- 59% of attacks occurred during the school day.

- 63% of attackers had a known history of weapons use.

- 68% acquired the weapon used from their own home or that of a relative.

- 93% of attackers planned out the attack in advance.

- 93% of attackers engaged in some behavior prior to the attack that caused others to be concerned.

- 95% of attackers were current students.

- 24% motivated by desire for attention or recognition.

- 27% motivated by suicide or desperation.

- 34% motivated by attempt to solve a problem.

- 54% had multiple motives.

- 61% motivated by desire for revenge.

- 75% felt bullied/persecuted/threatened by others.

Concerning Behaviors and Potential Warning Signs*

- Significant personal loss, humiliation, or setback that is either real or perceived.

- Inability to perceive or lack of interest in pursuing non-violent resolutions to a grievance.

- Deliberate or inadvertent disclosure of violent plans or of impending ominous events; verbal/written expressions of intent to commit highly dramatic acts (against self or others) in the near future.

- Pervasive, persistent fantasies where the offender victimizes others through dominant violence.

- Increasingly problematic or concerning interpersonal interactions with others. Others are concerned that the individual may become violent.

- Significantly diminished resiliency or compromised ability to cope with stressors or setbacks.

- Increased isolation, depression, and withdrawal from normally pleasurable activities. Decreased performance at school (may appear to be in a “downward spiral”).

- Contextually inappropriate or dramatically escalated interest in past attacks or attackers.

- Contextually inappropriate or dramatically escalated interest in obtaining firearms and/or explosives.

- Contextually inappropriate accumulation of or escalated interest in tactical gear, clothing or paraphernalia.

- Evaporating buffers and fading obstacles to violence (e.g. diminishing fear of death/incarceration; loss of stabilizing family member).

- Increasing sense of recklessness (e.g. financial, sexual) suggesting a disregard for future consequences.

- Pre-attack research and planning (e.g. site surveillance).

- Contextually inappropriate or dramatic change in appearance (e.g. hair, tattoos).

- Abrupt and unexplained cessation in the use of alcohol, drugs, and/or medications (“cleansing/purifying”).

- Creation of a “legacy token” (e.g. manifesto, video) designed to claim credit for an act of violence and to articulate motives behind an attack. Staging of the legacy token for distribution or discovery.

- Boundary probing/testing or circumnavigation of security measures to penetrate into a restricted area.

- Procuring the means for an attack (e.g. stockpiling of weapons/ammunition, IEDs).

- Pre-attack staging or “cocooning” in a secluded location to physically and mentally prepare for the attack.

Resources

- Persons suspected of planning a school shooting or other act of targeted violence should be reported via 911 to your local police department or school threat assessment team.

- The BAU’s Behavioral Threat Assessment Center (BTAC) is the only multi-agency behavioral threat assessment team in the U.S. Government. Requests for BTAC assistance can be made via the BAU Coordinator in your local FBI Field Office.

- “Making Prevention a Reality” is a helpful guide produced by the BAU, available for download at: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/making-prevention-a-reality.pdf/view