The following study on police armaments and militarization in several international jurisdictions was authored by researchers at the Law Library of Congress and released in September 2014.

Police Weapons in Selected Jurisdictions

- 105 pages

- September 2014

This report examines the weapons and equipment generally at the disposal of law enforcement officers in several countries around the world. It also provides, for each of these countries, a brief overview of the rules governing the use of weapons by law enforcement officers. Precise and reliable information on the weapons and equipment of some countries’ police forces was often difficult to find. Nevertheless, certain interesting facts and patterns emerged from the Law Library’s research.

II. Centralized and Decentralized Police Forces

Some countries examined in this report have a very unified and centralized police force. In the Netherlands, for example, a recent reform combined the former twenty-five regional forces into a single national police agency. South African and Israeli police forces are also organized at the national level. Many other countries, however, have several layers of police, with separate organizations at the national and local levels. Mexico, Argentina, Canada, and Australia, for example, have national-level police organizations as well as separate police bodies at the provincial, state, or territorial level. Estonia, Italy, and France have a national police, but some municipalities in these countries also have their own police forces.

In countries that have multilayered law enforcement, there can sometimes be significant differences between the national and the lower-level forces’ equipment. In France, for example, municipal police officers have access to a much more restricted array of weapons than members of the national force. This seems to be the exception rather than the rule, however. In most jurisdictions examined here, it appears that regional forces have access to roughly the same types of weapons and equipment as their national counterparts.

III. Police Weapons

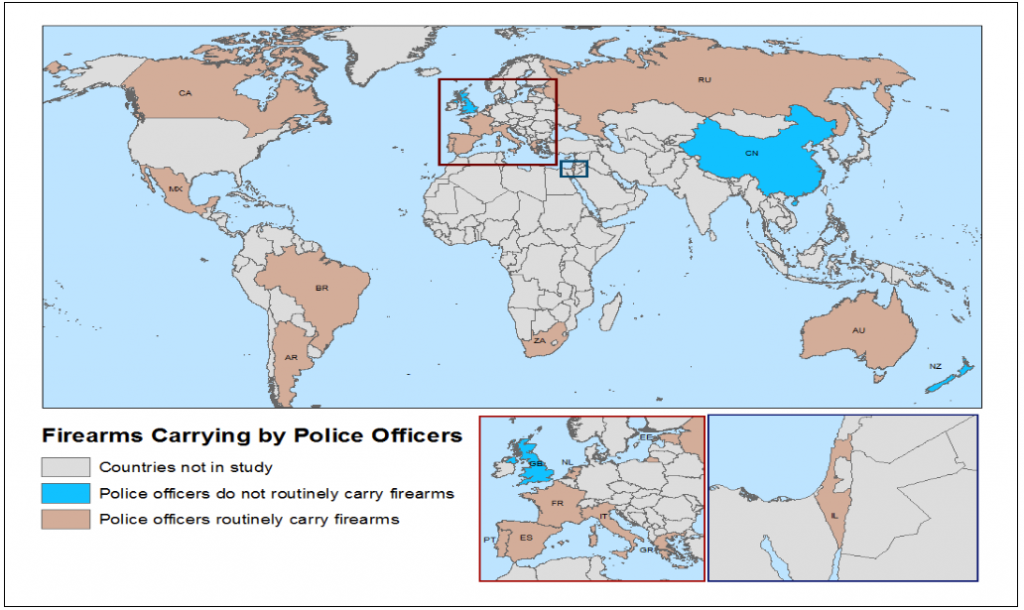

The basic individual police weapon in almost all the countries examined is the handgun. The United Kingdom, China, and New Zealand stand out as exceptions, as their police officers do not routinely carry firearms. Even in those countries, however, police officers have access to firearms to be used when necessary.

In addition to handguns, police officers often carry nonlethal devices such as batons, pepper spray or tear gas, and Tasers. Almost all of the police departments examined here appear to have access to rifles and/or shotguns, even if these are generally not carried by officers in their day-to-day functions. Many, including the Russian, Dutch, Canadian, and Estonian police, also have access to automatic weapons such as submachine guns.

Most countries equip at least one major law enforcement organization with armored vehicles and other types of military equipment. In contrast to the United States, where military involvement in civilian affairs is limited by statute, some countries have a major law enforcement body that is actually part of the military. France’s Gendarmerie nationale, for example, is a national-level law enforcement body that is part of the French military. The Netherlands has a similar corps called the Royal Netherlands Marechaussee, Spain has its Civil Guard, and Portugal has its National Republican Guard. It appears that these corps generally have access to heavier weaponry and more military-grade equipment than these countries’ civilian law enforcement agencies. French gendarmes, for example, may sometimes carry the French army’s standard assault rifle, and they have a number of wheeled armored personnel carriers at their disposal. The Royal Netherlands Marechaussee has a fleet of Lenco BEAR and BearCat armored vehicles. Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs Internal Troops are trained and equipped in much the same way as regular military forces.

Military police corps are not the only ones to have such heavy weapons and equipment, however. South African police forces have a number of armored vehicles, as do Australian state and territorial police forces, and some local Canadian police forces. Surveillance drones are used for law enforcement purposes in Portugal and the Netherlands. Mexican law restricts the use of certain equipment to the military, but Mexico’s Department of Defense may authorize law enforcement agencies to use such weapons. New Zealand’s police force does not appear to have its own fleet of armored vehicles, but it has an agreement with New Zealand’s armed forces by which it has access to the Army’s Light Armored Vehicles when necessary.

IV. Rules on the Use of Police Weapons

While certain basic principles appear to be universal among the countries studied in this report, there are notable differences in their rules on the use of police weapons, and especially on the use of firearms. One clear commonality is that police officers are almost always required to give warning before using a firearm, except if there is no time or if giving such a warning would cause more serious and dangerous consequences. Guidelines issued in Brazil in 2010 appear to go further in that they require police officers to use at least two nonlethal weapons before using a firearm, but there does not seem to be such a requirement in other countries.

In addition to this point, all of the countries in this report ostensibly follow the basic principles that the use of force must be necessary and proportional to the threat being countered. The Council of Europe has established a nonbinding Code on Police Ethics, which recommends that police only be authorized to use force when strictly necessary, and that such force be proportionate to the objectives pursued. Case law from the European Court of Human Rights also establishes the principle that police may only use deadly force when absolutely necessary. Non-European countries appear to follow the same basic principles as well. The appreciation of what is “necessary” and what kind of threats warrant the use of potential deadly force varies considerably, however.

In some countries, such as Brazil, France, and Spain, police officers may use their firearms only in self-defense or defense of others, and only if it is proportional to the threat.1 Some other jurisdictions give their police forces somewhat more leeway for the use of firearms. South Africa authorizes the use of deadly force not only when a suspect poses a threat of serious violence to the police officer or another person, but also when there is reasonable suspicion that the suspect has committed a crime in which he inflicted serious bodily harm or threatened to do so, and no other options are available for making an arrest. Similarly, Australia allows the use of deadly force in cases of self-defense and defense of others, or to stop someone who has been called on to surrender and who refuses, if that person cannot be apprehended in any other manner.

Russian law gives an exhaustive list of circumstances in which the use of firearms by law enforcement officers is authorized. This list includes self-defense and the protection of others, the apprehension of fleeing criminals, and the suppression of riots. Chinese law also provides a list of fifteen types of circumstances where police may use firearms, including preventing acts of violence, robbery of dangerous goods, sabotage of certain facilities, or resisting arrest for certain crimes.In many countries, including Brazil, Portugal, France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, any incident in which a police officer shoots someone automatically triggers an investigation or the requirement that a detailed report be made.

V. Controversies

Issues revolving around police weapons and equipment have been the root of debates in most of the countries examined here. Controversies range from disagreements over the use of drones by law enforcement in Netherlands, to the question of whether New Zealand police officers should routinely carry pistols. In addition, many countries have seen incidents where law enforcement officers were involved in controversial shootings of unarmed individuals.

…