Chatham House

- Institute of Iranian Studies, University of St. Andrews

- Edited by Professor Ali Ansari, Director, Institute of Iranian Studies, University of St. Andrews; Associate Fellow, Middle East and North Africa Programme, Chatham House; author, ‘Iran, Islam and Democracy’

- Research and Analysis by Daniel Berman and Thomas Rintoul, Institute of Iranian Studies, University of St. Andrews

- 19 pages

- Public

- June 21, 2009

Executive Summary

Working from the province by province breakdowns of the 2009 and 2005 results, released by the Iranian Ministry of Interior, and from the 2006 census as published by the official Statistical Centre of Iran, the following observations about the official data and the debates surrounding it can be made.

- In two conservative provinces, Mazandaran and Yazd, a turnout of more than 100% was recorded.

- At a provincial level, there is no correlation between the increased turnout and the swing to Ahmadinejad. This challenges the notion that Ahmadinejad’s victory was due to the massive participation of a previously silent conservative majority.

- In a third of all provinces, the official results would require that Ahmadinejad took not only all former conservative voters, all former centrist voters, and all new voters, but also up to 44% of former Reformist voters, despite a decade of conflict between these two groups.

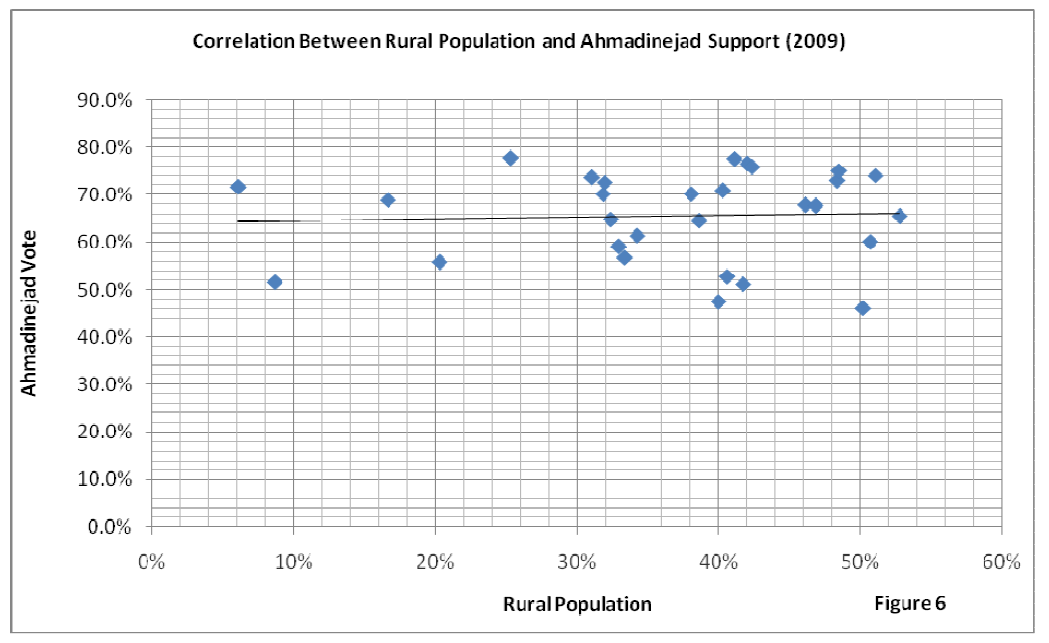

- In 2005, as in 2001 and 1997, conservative candidates, and Ahmadinejad in particular, were markedly unpopular in rural areas. That the countryside always votes conservative is a myth. The claim that this year Ahmadinejad swept the board in more rural provinces flies in the face of these trends.

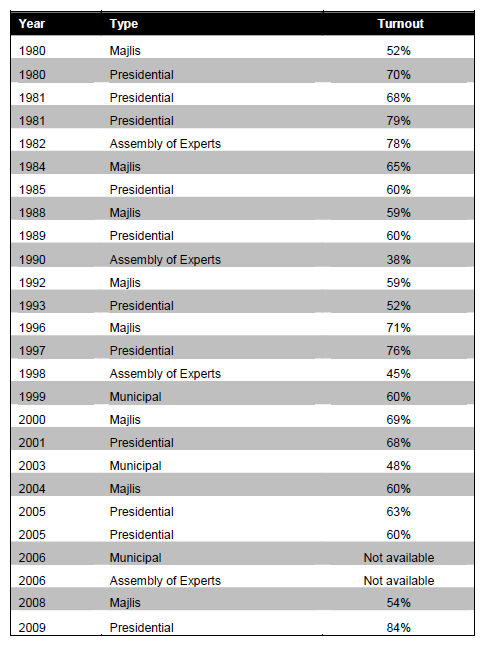

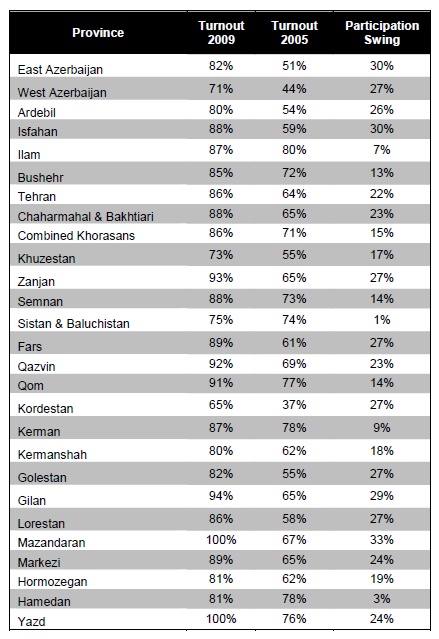

1. Irregularities in Voter Turnout

Two provinces show a turnout of over 100% and four more show a turnout of over 90%. Regional variations in participation have disappeared. There is no correlation between the increase in participation, and the swing to Ahmadinejad. Firstly, across the board there is a massive increase in turnout, with several provinces increasing their participation rate by nearly 75%. This increase results in substantially less variation in turnout between provinces, with the standard deviation amongst provincial turnouts falling by just over 23% since 2005. The 2005 results show a substantial turnout gap, with seven provinces recording turnout below 60%, and ten above 70%. In 2009, only two were below 70% and 24 were above 80%. In fact, 21 out of 30 provinces had turnouts within 5% of 83%. The data seems to suggest that regional variations in participation have suddenly disappeared. This makes the evident lack of any sort of correlation between the provinces

that saw an increase in turnout and those that saw a swing to Ahmadinejad (Fig.1) all the more unusual. There is no significant correlation between the increase in participation for a given province and the swing to Ahmadinejad (Fig.1). This lack of correlation makes the argument that an increase in participation by a previously silent conservative majority won the election for Ahmadinejad somewhat problematic.

Furthermore, there are concerns about the numbers themselves. Two provinces, Mazandaran and Yazd, have results which indicate that more votes were cast on 12 June than there were eligible voters and that four more provinces had turnouts in the mid-nineties. In a country where allegations of ‘tombstone voting’ – the practice of using the identity documents of the deceased to cast additional ballots – are both longstanding and widespread, this result is troubling but perhaps not unexpected. This problem did not start with Ahmadinejad; according to official statistics gathered by the International institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance in Stockholm, there were 12.9% more registered voters at the time of Mohammed Khatami’s 2001 victory than there were citizens of voting age. In conclusion, a number of aspects of the reported turnout figures are problematic. The massive increases from 2005, the collapse of regional variations, and the absence of any clear correlation between increases in turnout and increased support for any candidate on their own make the results problematic.…

This data supports the contention of academic experts on rural Iranian politics that rural voters have not been the dedicated Ahmadinejad supporters occasionally described in western media. This is supported by the fact that much of Iran’s rural population is comprised of ethnic minorities: Lors, Baluch, Kurdish, and Arab amongst others. These ethnic minorities have a history both of voting Reformist and of voting for members of their own ethnic group. For example, they were an important segment of Khatami’s vote in 1997 and 2001 and voted largely for Karrubi and Mostafa Moin in 2005. The 2009 data suggests a sudden shift in political support with precisely these rural provinces, which had not previously supported Ahmadinejad or any other conservative (Fig.5) showing substantial swings to Ahmadinejad (Fig.6). At the same time, the official data suggests that the vote for Mehdi Karrubi, who was extremely popular in these rural, ethnic minority areas in 2005, has collapsed entirely even in his home province of Lorestan, where his vote has gone from 440,247 (55.5%) in 2005 to just 44,036 (4.6%) in 2009. This is paralleled by an overall swing of 50.9% to Ahmadinejad, with official results suggesting that he has captured the support of 47.5% of those who cast their ballots for Reformist candidates in 2005. This, more than any other result, is highly implausible, and has been the subject of much debate in Iran. This increase in support for Ahmadinejad amongst rural and ethnic minoritiy voters is out of step with previous trends, extremely large in scale, and central to the question of why (or indeed whether) he won in June 2009.