COMMANDER’S GUIDE TO MWDs HANDBOOK

- 85 pages

- REL NATO, GCTF, ISAF, MCFI, ABCA

- For Official Use Only

- 2009

Dogs have a long history in war, dating back to ancient times. The first-recorded American use of military dogs was during the Seminole War of 1835 when the Army used Cuban-bred bloodhounds for tracking. In more modern times, military working dog (MWD) numbers and uses have greatly expanded. The Army established a “War Dog” program in the Quartermaster Corps in 1942. By the end of the war, more than 10,000 dogs were employed in both the European and Pacific theaters of operations. While most dogs were employed for sentry duty at fixed installations for force protection, they also performed scout duties in combat.

In 1951 during the Korean Conflict, responsibility for military dogs was transferred to the Military Police Corps. Dogs were employed in Korea for sentry duty and in support of combat patrols. More than 4,000 dogs were employed in the Vietnam War, performing a wide variety of tasks such as combat patrol, critical site security, narcotics and explosives detection, and riot control. Dogs were also used extensively as a critical element of combat tracker teams. This team’s primary mission was to conduct reconnaissance in order to fix the enemy’s position or to reestablish contact. The U.S. Army Infantry School played a prominent role in developing MWDs for combat operations. This role included operating scout dog training programs at Fort Benning, GA, and in Vietnam and establishing infantry-manned, scout dog platoons employed in support of combat operations.

The MWD program endured four decades of peace and brief contingency operations from the end of the Vietnam era to the current Global War on Terrorism. The program remained firmly embedded in the Military Police Corps combat support, law and order, and force protection missions. In late 2001, the onset of military operations in Afghanistan provided the impetus to expand MWD capabilities in support of commanders in the field. In 2002, as a direct result of an immediate operational need in Afghanistan, Army leadership directed the establishment of an Army mine detection dog unit and embedded it in the Corps of Engineers. In 2004, as a result of cooperation between the U.S. Army Engineer School and the U.S. Army Military Police School, the Army added a non-aggressive, specialized search dog (explosives detection dog) to the MWD inventory. Combat tracker dogs are returning to Army use as well, along with a very limited number of human remains detector or cadaver search dogs. Two constants emerge in the 60-plus-year history of Army MWD use: working dogs are used in a variety of units for a wide range of missions, and the size of the MWD program has expanded and contracted over time based on the needs of the Army. In the current and projected future operating environment, the MWD program will undoubtedly expand once again.

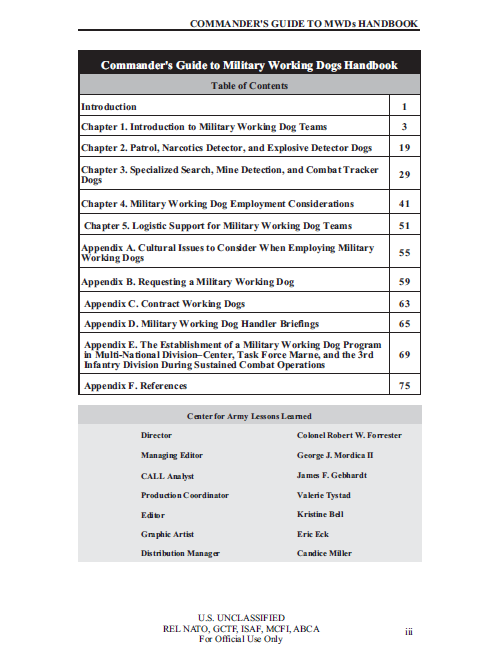

With such a broad array of MWDs available to the tactical commander, many in the MWD community felt commanders needed a users’ guide. This handbook describes the types of MWDs that are currently available for tactical use; offers some tactics, techniques, and procedures for their use in common tactical missions; lays out many issues for the tactical commander to consider in the use of MWD teams; and suggests logistic support required for MWD use. Appendices describe cultural considerations for the use of MWDs, explain how to obtain MWD team support in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and relate how one Army division established its own MWD capability in Iraq. In addition, there are a few cautionary remarks about the use of contract working dogs.

Insights gained from reading this handbook will assist tactical commanders in selecting the appropriate MWD for a mission, thus maximizing both the possibility of mission success and the effective use of an important enabler.