DODD 5100.01 tasks the Army to “train and equip, as required, forces for airborne operations, in coordination with the other military Services, and in accordance with joint doctrine.” This guidance directs the Army, which has primary responsibility for the development of airborne doctrine, procedures, and techniques, to develop, in coordination with the other military Services, doctrine, procedures, and equipment that are of common interest.

…

Special operations forces must conduct a detailed mission analysis to determine an appropriate method of infiltration. MFF operations are one of the many options available to a commander to infiltrate personnel into a designated area of operations. MFF operations are ideally suited for, but not limited to, the infiltration of operational elements, pilot teams, pathfinder elements, special tactics team assets, and personnel replacements conducting various missions across the operational continuum. A thorough understanding of all the factors impacting MFF operations is essential due to the inherently high levels of risk associated with MFF operations. The objective of this chapter is to familiarize the reader with MFF operations and to outline the planning considerations needed to successfully execute MFF operations.

…

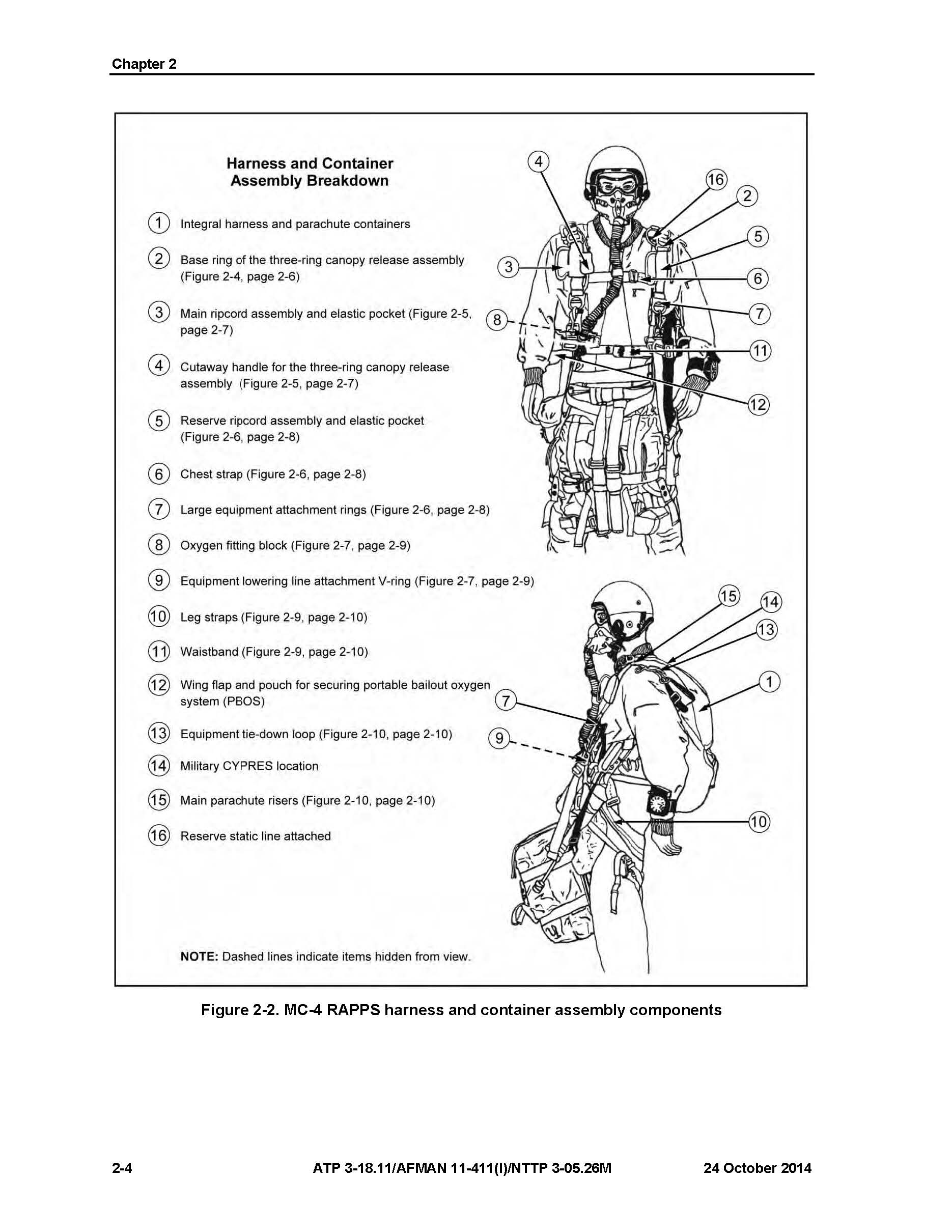

1-1. MFF parachute operations are used when enemy air defense systems, terrain restrictions, or politically sensitive environments prevent low-altitude penetration or when mission needs require a clandestine insertion. MFF parachute infiltrations are conducted using the RAPPS, which is a high-performance gliding system. The RAPPS is a highly maneuverable parachute that has forward airspeeds of 20 to 30 mph. The RAPPS can be manually deployed during free fall or with the assistance of a static line, depending on mission and jumper capabilities. The glide capability of the RAPPS provides commanders the means to conduct standoff infiltrations of designated areas without having to physically fly over the target area. This process allows commanders to keep high-value air assets outside the detection and threat ranges of enemy air defense systems or politically sensitive areas.

1-2. MFF parachuting allows special operations forces personnel to deploy their parachutes at a predetermined altitude, assemble in the air, navigate under canopy, and land safely together as a tactical unit ready to execute their mission. Although free-fall parachuting can produce highly accurate landings, it is primarily a means of entering a designated impact area within the objective area. The following are two basic types of MFF operations:

HALO. HALO operations are jumps made with an exit altitude of up to 35,000 feet mean sea level (MSL) and a parachute deployment altitude at or below 6,000 feet above ground level (AGL). HALO infiltrations are the preferred MFF method of infiltration when the enemy air defense posture is not a viable threat to the infiltration platform or when a low opening will not compromise the team’s position on infiltration. HALO infiltrations require the infiltration platform to fly within several kilometers of the DZ.

HAHO. HAHO operations are standoff infiltration jumps made with an exit altitude of up to 35,000 feet MSL and a parachute deployment altitude at or above 6,000 feet AGL to 25,000 feet AGL. HAHO infiltrations are the preferred method of infiltration when the enemy air defense threat is viable or when a low-signature infiltration is required. Standoff HAHO infiltrations provide commanders a means to drop MFF parachutists outside the air defense umbrella, where they can navigate undetected under canopy to the DZ or objective area. The most important objective of a HAHO is for team members to land together, even if circumstances force the team to land in an area that might not have been the original landing zone. Sometimes it is necessary to choose an alternate suitable area close to the objective area that provides the advantages of a clandestine insertion.

…

…

HYPOXIA

4-4. Hypoxia is a condition caused by lack of oxygen. A reduction in the partial pressure of oxygen in the atmosphere occurs as the parachutist ascends. When the parachutist inhales, he receives fewer oxygen molecules. The reduction of the partial pressure inhibits the body’s ability to transfer oxygen to the tissues. The most common symptoms of hypoxia are blurred or tunnel vision, color blindness, dizziness, headache, nausea, numbness, tingling, euphoria, belligerence, loss of coordination, and lack of good judgment. Corrective action for a parachutist who becomes hypoxic is to place him on 100-percent oxygen and inform the jumpmaster and/or physiological technician. In extreme cases, it may be necessary to descend the aircraft and evacuate the parachutist to the nearest medical facility. If hypoxia goes unrecognized and uncorrected, it can result in seizures, unconsciousness, or even death.

DECOMPRESSION SICKNESS

4-5. Decompression sickness is a condition caused by the release of nitrogen from body tissues. It usually occurs during unpressurized flights above 18,000 feet MSL, but can occur at lower altitudes. Many factors contribute to decompression sickness. Facial hair can cause an insufficient seal of the oxygen mask to the parachutist’s face, rendering prebreathing ineffective. Poor physical conditioning and fatigue will make the individual more susceptible to decompression sickness. Alcohol use dehydrates the body, constricting the capillaries and decreasing the efficiency of the cardiovascular system. Nicotine from tobacco use hardens arteries and restricts blood flow to the capillaries, reducing the efficiency of the cardiovascular system. Smoking also reduces the efficiency of the lungs. Parachutists should know the symptoms of decompression sickness and constantly monitor themselves on board the aircraft and after return to the ground. Some parachutists may have symptoms of decompression sickness during flight that are not readily noticeable. Minor symptoms may be confused with discomfort from the parachute and equipment. Other individuals may choose not to report what may be considered to be minor problems. Although these symptoms usually resolve upon the jumper’s return to ground, some personnel may continue to have symptoms. These individuals require prompt medical evaluation since their illness is more severe.

4-6. There are four types of decompression sickness: the bends, chokes, neurological (central nervous system) hits, and skin manifestations. Each of these is discussed in the following paragraphs.

The Bends

4-7. The bends are the most common type of decompression sickness. The most frequent symptom is a deep, dull, and penetrating pain in major movable joints that can increase to agonizing intensity. This pain may be significant enough to make the parachutist feel as if he cannot move the joint. The affected parachutist might also go into shock. Corrective action for a parachutist who experiences the bends is to—

- Place him on 100-percent oxygen.

- Inform the jumpmaster and/or physiological technician.

- Descend the aircraft and pressurize the cabin to as close to sea level as possible.

- Evacuate to the nearest medical facility with a recompression chamber. A flight surgeon or aeromedical examiner will determine if compression therapy is required.

…

MAIN RIPCORD PULL

7-2. The parachutist executes the main ripcord pull at the predesignated altitude. He looks at the main ripcord handle on the right main lift web. He extends his left arm beyond his head with his hand held palm down. He traces the main ripcord cable housing. He grasps the main ripcord handle with his right hand, pulls the handle from the ripcord pocket, pulling the main ripcord cable to full-arm extension. Then he raises his right shoulder to disrupt the partial vacuum while looking straight down. After canopy deployment, he slips the main ripcord handle over his wrist.

7-3. When the parachutist uses night vision goggles (NVGs) to assist him during a night jump, the pull sequence during opening will remain the same as without NVGs (Figure 7-8, page 7-6). The parachutist will—

Look below the NVGs to identify and read the altimeter, ripcord, cutaway pillow, and reserve ripcord handle when required during free-fall and canopy descent.

“Arch-Look-Trace-Grab” as normal. The counter hand will extend slightly more forward to allow the head to be cradled under the parachutist’s arm in a manner that protects the NVGs from inadvertent contact with the deploying pilot chute.

Pull the ripcord handle to full-arm extension while continuing to look straight down with the counter arm in place to continue protecting the NVGs from a deploying pilot chute.

Not conduct a visual check of the pilot chute; the parachutist will raise his right shoulder in an attempt to disrupt the partial vacuum while continuing to look straight down. He will attempt this twice and only twice; if this is unsuccessful, he will perform cutaway procedures for a total malfunction.