TC 31-20-2 Special Forces Handbook for the Fingerprint Identification System

- 50 pages

- Distribution authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors only to protect technical or operational information from automatic dissemination under the International Exchange Program

or by other means. - September 2008

- 3.05 MB

1-1. Special Forces (SF) Soldiers use various biometric identification systems in SF operations. Biometric applications are fundamental to a wide array of SF operational activities, including, but not limited to, the growing field of SF sensitive site exploitation (SSE) and the range of unit protection activities. SSE applications include the identification of enemy personnel and cell leaders in a counterinsurgency (COIN) environment following tactical operations, particularly during direct action missions. Unit protection applications include maintaining databases on the identities of both United States Government (USG) and local national personnel. A routine example of protection applications for biometric data include the requirement to maintain isolated personnel report (ISOPREP) cards, which are fundamental to personnel recovery (PR) operations for the recovery of isolated, missing, detained, or captured (IMDC) personnel; ISOPREP cards are essential for the authentication of the IMDC individual. Another example of the use of biometric identification in SF operations is for positive identification of local national workers in a combat environment at an SF tactical facility, such as at a firebase. Whether in a garrison or combat environment, the collection, transmission, and storage of biometric data is a critical and common component of SF unit operations.

1-2. The most common and reliable means of identifying a person through biometric means is by the fingerprint identification system (FIS). Since 2001, SF has principally used technological (digital) means to take and transmit fingerprints to an automated fingerprint identification system (AFIS). However, although there are many technological capabilities to accomplish this task at the disposal of U.S. forces, it may not always be feasible to use advanced technological means to take, transmit, and/or store fingerprint data. Therefore, SF Soldiers—particularly the SF intelligence sergeants, military occupational specialty 18F—must be familiar with both the traditional (manual) means of fingerprinting and with the modern (digital) means available to Special Forces operational detachments (SFODs). Therefore, this TC covers both manual fingerprinting systems and some of the current digital systems available to the SFOD.

1-3. Manual FISs are still required in a wide array of SF operations. For example, situations may arise when digital FIS equipment or adequate power supply is inoperable, damaged, or not properly calibrated—simply put, there are times when even the most advanced and useful technology fails. In addition, given that the vast majority of SF operations are conducted “by, with, and through” indigenous forces, SF has a requirement to train, assist, and advise host nation (HN) regular and/or irregular forces who require FISs, but do not have advanced technological means. Likewise, even when digital FISs are available and the HN assets are capable of using them, it may be impractical or unwise to hand over these instruments. An example of this would be in an unconventional warfare environment; it may not be advisable to give digital FIS equipment to an irregular asset. In such a case, it may be necessary for the SF Soldier to read fingerprints from a paper provided by the asset. Some of the factors that must be considered before coming to this conclusion include the following:

- What is the classification restriction of the equipment and its capabilities?

- What are the consequences to the irregular asset and the USG if the asset is caught with this equipment?

- How hard is it to replace this equipment if it is turned over to the asset?

- Is there an available funding authority to procure the necessary equipment for indigenous personnel?

- Can the linkage of this equipment to the United States be avoided if necessary?

- How likely is it that the equipment is available to anyone other than the United States?

- How likely is the discovery of this equipment and its capabilities to cause embarrassment to the United States or its allies?

- How difficult is it to maintain the equipment and is the asset capable of accomplishing that maintenance without assistance?

- Is there another alternative to accomplish the task without losing physical control over the technical equipment?

- With all of these factors taken into consideration, is there a nontechnical means to accomplish the task which will reduce the various risks and is less resource intense?

1-4. In the event the irregular asset provides a set of prints on a plain piece of paper or other suitable surface, the SF Soldier must be able to read, categorize, and format the prints in order to transmit them to the AFIS for positive identification. The information in this TC is designed to enable SF Soldiers to become familiar enough with the FIS to not only use the equipment and techniques, but also to train an irregular asset to provide this service, such as when operating as part of an unconventional assisted recovery team (UART) in a PR scenario. These are critical skills; in the case of a UART, the SF Soldier accomplishing this task will have to be proficient enough in the FIS to successfully complete the authentication of the IMDC individual.

1-5. This TC explains how to take a set of fingerprints, read the fingerprints manually (when necessary), and transmit the results. Transmission includes the proper message format for transmitting FIS data over radio when fully digital file transfer capability is not available.

FINGERPRINTING BASICS

1-6. Manual FISs are the most basic and are still an effective means of identification. For many years fingerprinting was—and even in the United States sometimes still is—performed manually without the aid of current technology. There remain dedicated assets within the USG (the Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI], for example) that can manually read fingerprints. Although technological mechanisms involving a live scan of a fingerprint to the Biometric Fusion Center (BFC) are routinely capable of receiving and validating the fingerprints in less than 10 minutes, even manual FIS validation can be relatively quick. Under ideal conditions and with a clear set of fingerprints, the manual technique can take as little as 30 minutes when properly done. Even without a live scan device, fingerprints taken by a manual FIS may be transmitted and analyzed using digital devices. Once captured, the fingerprint must be photographed and scanned to send it over the portal or read and converted into a message format for transmittal over a tactical radio or phone. This hybrid manual/digital approach offers added flexibility and a relatively rapid response to the SFOD.

1-7. Traditionally, ink and paper are used to capture fingerprints. This method can be done on living and deceased suspects. When traditional ink and cards are not available, field-expedient methods are applied. Blank paper may be used in the absence of a fingerprint card—lined paper should be avoided. Substitutes for ink can be lipstick, charcoal, camouflage paint, magic marker, and even blood.

1-8. Standard ink and the standard FBI applicant card (covered in Chapter 2) should be used whenever possible. The FBI applicant card can be scanned and photographed as is for transmission to the BFC because the FBI card is a known size and shape. Fingerprint cards from other countries require a scale in the photograph or scan.

1-9. A metric scale should be in the photo or scan. Even if the scale is not metric, it gives the examiner a reference. When there is no metric scale available to use, a common item to size the print must be included, such as a dollar bill scanned with the print, to provide a reference.

1-10. Lifting a fingerprint is easiest when done from a smooth (nonporous) object. Semi-porous and porous objects generally require chemicals; therefore, they must be sent to a lab for proper processing. If the item cannot be removed, a photograph may be the only way to retrieve the fingerprint.

1-11. In the event a traditional latent print cannot be lifted and it is necessary to photograph the print, the following are some of the keys to taking a quality photograph of a fingerprint:

- Latent images need to be 1000 pixels per inch (ppi) and a file type of Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) 2000, Tagged Image File Format (TIFF), or bitmap (BMP). The image should not be saved as a Portable Document Format (PDF) or regular JPEG.

- A scale should always be included in the image—preferably metrics rather than inches. The scale should lay flat on the same plane as the latent print for proper calibration. If the technician reading the print cannot accurately calibrate for size, the AFIS search will be inaccurate.

- When photographing, the camera should be mounted on a tripod and at a 90 degree angle so that the lens is parallel to the latent print being photographed to prevent parallax distortion.

- Since images can only be posted to the portal one at a time, each image should be labeled beginning with a case number and then the image number so that multiple postings can be associated with one case; for example, 07-101-2 = case #07-101, latent image 2.

- One of the most common mistakes when powdering latent prints is to over-powder. Less powder is usually better. A little more powder can be added if the print is too light. Too much powder, however, can fill in the furrows and obscure the fine detail of a fingerprint.

- The technician should not twist the fingerprint brush between his fingers when powdering (like the actors do on television). This method reduces the control over the brushing motion and can damage the print, as well as pull powder between the ridges into the furrows, reducing the quality. It is best to start brushing lightly in an area and when ridge detail begins to appear, try to brush with the ridge flow, not against it.

- Sometimes multiple lifts of the same latent can be taken. This would be done, for example, when it looks like there is too much powder. After one lift, the technician should try to “clean up” the print by lightly brushing with the ridge flow and not adding more powder to the brush—it should still have some powder on it from the previous “dusting,” and then take a second lift to see if the quality improves. The technician must be sure to always clearly mark on the lift card if multiple lifts are taken of the same latent so that if someone is identified, it does not look as if they were identified to multiple latents when in fact it is just one. The technician should always ensure a photograph is taken before attempting to “improve” a print in the event the attempt results in irreparable damage to the quality of the print.

…

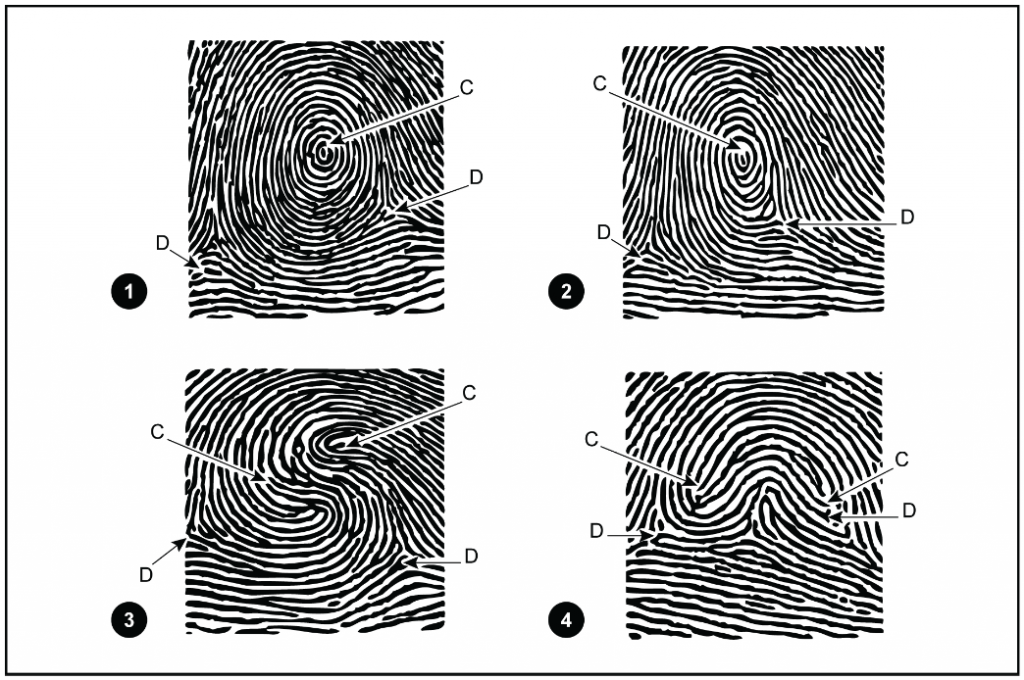

1-25. No matter how definite fingerprint rules and pattern definitions are made, there will always be some patterns causing doubt as to their classification. The primary reason for this doubt is that no two fingerprints will ever appear that are exactly alike. Other reasons are differences in the degree of judgment and interpretation of the individual analyzing the fingerprints. The correct interpretation of patterns that are questionable because of their resemblance to more than one pattern type is determined by the analyst’s proficiency in determining focal points, cores, and deltas. The more skilled the analyst is in reading the prints, the fewer questionable patterns are encountered. For positive identification, there is no allowable error for the type of print. The print may be questionable and stated as such in the FIS message. In questionable prints, the procedures described below help to identify the individual.