The following training circular was released by the U.S. Army in January 2014.

TC 7-100.3 Irregular Opposing Forces

- 210 pages

- January 17, 2014

- 6 MB

Irregular forces are armed individuals or groups who are not members of the regular armed forces, police, or other internal security forces (JP 3-24). The distinction of being armed as an individual or group can include a wide range of people who can be categorized correctly or incorrectly as irregular forces. Excluding members of regular armed forces, police, or internal security forces from being considered irregular forces may appear to add some clarity. However, such exclusion is inappropriate when a soldier of a regular armed force, policeman, or internal security force member is concurrently operating in support of insurgent, guerrilla, or criminal activities.

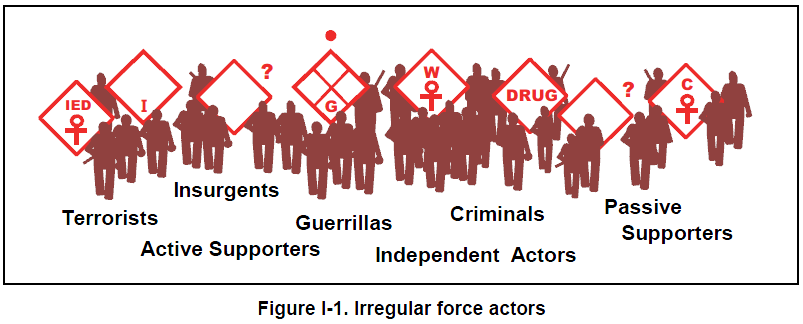

Irregular forces can be insurgent, guerrilla, or criminal organizations or any combination thereof. Any of those forces can be affiliated with mercenaries, corrupt governing authority officials, compromised commercial and public entities, active or covert supporters, and willing or coerced members of a populace. Independent actors can also act on agendas separate from those of irregular forces. Figure I-1 depicts various actors that may be part of or associated with irregular forces.

Closely related to the subject of irregular forces is irregular warfare. JP 1 defines irregular warfare as “a violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant population(s). Irregular warfare favors indirect and asymmetric approaches, though it may employ the full range of military and other capacities, in order to erode an adversary’s power, influence, and will.” The definition spotlights a dilemma of conflict in and among a population. It also indicates that the non-state actors characterized as irregular forces may operate in other than military or even military-like (paramilitary) capacities.

IRREGULAR OPFOR AND HYBRID THREAT FOR TRAINING

The function of the OPFOR is to portray a threat or enemy in training exercises. Army Regulation (AR) 350-2 establishes policies and procedures for the Army’s Opposing Force Program. Since 2004, that AR has defined opposing force as “a plausible and flexible military and/or paramilitary force representing a composite of varying capabilities of actual worldwide forces used in lieu of a specific threat force, for training or developing U.S. forces.” AR 350-2 has defined threat as “any specific foreign nation or organization with intentions and military capabilities that suggest it could become an adversary or challenge the national security interests of the United States or its allies.” However, that definition of threat was much narrower than the way ADRP 3-0 now defines it.

“A threat is any combination of actors, entities, or forces that have the capability and intent to harm U.S. forces, U.S. national interests, or the homeland. Threats may include individuals, groups of individuals (organized or not organized), paramilitary or military forces, nation-states, or national alliances. When threats execute their capability to do harm to the United States, they become enemies.” (ADRP 3-0) A hybrid threat is the diverse and dynamic combination of regular forces, irregular forces, terrorist forces, and/or criminal elements unified to achieve mutually benefitting effects (ADRP 3-0). A hybrid threat can consist of any combination of two or more of those components.

The preface of TC 7-100 says that TC outlines “the Hybrid Threat that represents a composite of actual threat forces as an opposing force (OPFOR) for training exercises.” After focusing on real-world hybrid threats in its first part, TC 7-100 states: “Part two of this TC focuses on the Hybrid Threat (HT) for U.S. Army training. The HT is a realistic and relevant composite of actual hybrid threats. This composite constitutes the enemy, adversary, or threat…represented as an opposing force (OPFOR) in training exercises.” That means that, in the context of the HT for training, the OPFOR can also include nonmilitary actors (such as criminal elements), which are part of the threat faced by the training unit. Since the definition of hybrid threat includes other than military and paramilitary actors, it has broadened the application of the term OPFOR.

The AR 350-2 definition of OPFOR used the term paramilitary forces, defined in JP 3-24 as “forces or groups distinct from the regular armed forces of any country, but resembling them in organization, equipment, training, or mission.” However, the ADRP 3-0 (and TC 7-100) definition of hybrid threat uses the broader term irregular forces, defined in JP 3-24 as “armed individuals or groups who are not members of the regular armed forces, police, or other internal security forces.” Thus, irregular forces would include paramilitary forces, but also other armed individuals or groups that do not resemble regular armed forces. Although the ADRP 3-0 definition of hybrid threat includes “terrorist forces, and/or criminal elements,” both criminals and actors who use terrorism as a tactic would actually fit under the JP 3-24 definition of irregular forces.

FM 7-100.4 lists criminal organizations under non-state paramilitary actors, but only because “Criminal organizations at the higher end of the scale can take on the characteristics of a paramilitary organization.” However, it notes that “individual drug dealers and criminals or small-scale criminal organizations (gangs)” do not have that type of capability. FM 7-100.4 also refers to “other armed combatants” as “nonmilitary personnel who are armed but not part of an organized paramilitary or military structure. Nevertheless, they may be disgruntled and hostile.” ARDP 3-0 defines “a party identified as hostile against which the use of force is authorized” as an enemy. In a training exercise, such an enemy would be portrayed as part of the OPFOR.

FM 7-100.4 also recognizes the category of “unarmed combatants.” It says: “The local populace contains various types of unarmed nonmilitary personnel who, given the right conditions, may decide to purposely and materially support hostilities against the United States. … Individual criminals or small gangs might be affiliated with a paramilitary organization and perform support functions that do not involve weapons. … Even unarmed individuals who are coerced into performing or supporting hostile actions and those who do so unwittingly can in some cases be categorized as combatants. Thus, various types of unarmed combatants can be part of the OPFOR.”

Thus, a threat or enemy can be any individual or group—not necessarily military and/or paramilitary, or even armed. The same is true of the OPFOR that represents the threat or enemy in a training exercise.

…

MOTIVATIONS

1-47. Insurgents and guerrillas are normally motivated by social, religious, or political issues or some combination of those. In most cases, criminals—whether they are part of the irregular OPFOR or not—have other motivations. Although individual actors who conduct criminal activity may not be part of the irregular OPFOR, the individual’s personal motivation and/or ideology may be the deciding perspective of why he or she acts.

Note. The local populace may provide active or passive support out of a different motivation than the insurgents or guerrillas they support. For example, the motivation of the populace might be financial (payment or beneficial effects on business profits) or security provided them. The populace might provide support, based on ethnic or religious issues, to an insurgent or guerrilla organization even if they do not share that organization’s political agenda.

INSURGENTS OR GUERRILLAS

1-48. Certain types of motivation are common to insurgents and guerrillas, the two most likely components of the irregular OPFOR. However, insurgents and guerrillas that agree to collaborate against a common enemy may or may not share the same motivations or ideology.

Note. If multiple insurgent and/or guerrilla organizations exist in a particular OE, they may share some motivations but differ in others. In order to form an affiliated relationship, the organizations just need to have one or more motivations that coincide with or complement each other. An example of a coinciding motivation could be that both organizations resent the presence of an extraregional force in their country. An example of a complementary relationship would be if one organization has financial resources, while the other needs financial support.

1-49. The motivation that incites violent as well as nonviolent actions by the irregular OPFOR is often framed in the context of ideology. The irregular OPFOR acts in a particular way based on underlying grievances, which are often linked to the ideals of an ideology. These unresolved grievances—perceived or factual—create conditions where armed and unarmed individuals believe they must act to obtain what they believe is a just solution. The rationale and the resulting actions may be perceived in a positive and negative light by a relevant population. The motivation and rationale typically are one or more of the following:

– Personal or group social identity.

– Devotion to a particular religious belief.

– Commitment to a form of political governance.Combinations among these factors can further complicate how to describe the motivation and ideology of a particular person or group. Other motivations exist and may become a primary prompt for action, though only loosely associated with a social, religious, or political agenda. Aspects of ethnicity, geography, and history affect personal and group relationships as witnessed in social status and networks, religion, and politics. Combinations can occur among these factors to further complicate how to describe the motivation of a particular person or group.

Social Identity

1-50. Social identity, as an individual and/or as a member of a social group, is often a fundamental aspect of why people may be aligned with or alienated from the irregular OPFOR. They may be attracted by an ability to satisfy a perceived critical want or need in their lifestyle. Allegiance to a clan, tribe, or familial grouping is an example of social identity and accountability. These forms of social allegiance can indicate why change is desired or required in a social order. The same rationales can support why a set of ideals or practices must be sustained or expanded within a relevant population. Several common categories of social identity that can overlap with religious or political agendas are as follows:

– Ethnocentric groups who understand race or ethnicity as the defining characteristic of a society and basis of cohesion.

– Nationalistic groups who promote cultural-national consciousness and perhaps establishment of a separate nation-state.

– Revolutionary groups who are dedicated to the overthrow of a governing authority and establishment of a new social order.

– Separatist groups who demand independence from an existing governance that appears socially, theologically, or politically unjust to a relevant population.1-51. A variation on these identity categories is an independent actor who conceives, plans, and conducts violent or nonviolent actions without any direction from another person or irregular force. This type of individual may be sympathetic to the aims of a particular group, but have no contact with the group or affiliated members of the group.

Religion

1-52. Religion can be a compelling motivation. As a personal belief, religion can be interpreted as divine edict and infallible. Practice of a faith system is a personal interpretation and decision. However, fundamentalist clerics and/or religious mentors in some instances can interpret passages of religious doctrine in a particular way that supports the irregular OPFOR agenda. Some interpretations may be a purposeful misrepresentation never intended by an original religious author. Other clerics or radical splinter groups may honestly believe in a religious duty to pursue a fundamentalist approach to worship and lifestyle. In either case, religion can be used as a catalyst to instigate rivalry between and among ethnic and/or religious denominational groups. Confrontations can be provoked by faith system practices that are completely unacceptable to another faith group and/or can create an irreconcilable theological wedge between cultural-faith groups in a relevant population.

1-53. The irregular OPFOR may attempt to link religion with declarations that governing political authorities who do not accept a particular understanding of a faith doctrine are a wicked secular presence that must be destroyed and replaced with a fundamentalist theocracy form of governance. Cults, although not a religion by normal definition, can adopt similar forms of violence, mass murder, and mayhem as part of a self-proclaimed apocalyptic vision and purpose.

Politics

1-54. The irregular OPFOR, especially the insurgent part, can have a political agenda. Prevalent political systems that can be promoted by the irregular OPFOR include forms of governance such as—

– Single-party totalitarian state.

– Nationalist-fascist authority.

– Leadership appointed or democratically elected by popular vote.

– Social self-management and equality aimed at reducing or eliminating political and economic hierarchies.

– Social-political process that evolves toward a classless-stateless society with common ownership on means of production, communal access to commodities for livelihood, and general social programs for the benefit of community and human wellness.

– Pseudo-social and political authority that protects a geographic sanctuary and/or safe haven for conduct of an illicit commercial enterprise.1-55. The irregular OPFOR can use motivations of a political ideology to attract the attention of a relevant population in order to develop influence with a particular community. This can lead to support and/or collaboration or actually joining the irregular OPFOR. Since politics are integral to the overarching conditions that affect daily life, commerce, vocation, freedoms, and family, the irregular OPFOR can use political influence—along with social and/or religious appeal—to enhance its legitimacy. Visible actions, often localized in perspective, focus on demonstrating power and authority.

…

BLURRING OF CATEGORIES

1-72. Although three basic types of forces can be part of the irregular OPFOR, the distinctions among insurgents, guerrillas, and criminals are sometimes blurred. That is because they may have more in common than they have that is different. From the viewpoint of the existing government authority, for instance, the activities of all three types are illegal, that is, criminal. Not just criminals but also insurgents and guerrillas can engage in criminal activities. Some insurgent organizations can include guerrilla units (developed from within or affiliated) and some guerrilla units may be part of an insurgency. In advanced phases of an insurgency, guerrilla units may begin to look and act more like regular military units.

1-73. There are three general tactics available to the irregular OPFOR—

– Military-like functional tactics.

– Criminal activity.

– Terrorism.1-74. At any given time, the irregular OPFOR could use any of these means. The differences among these three can become blurred, especially within an urban environment or where the governing authority exerts strong control.

…

Intellectual Property Crimes

4-96. Intellectual property crimes involve theft of material protected by copyright, trademark, patent, or trade-secret designation. Such intellectual property is vital to local, national, and international economies.

4-97. The interconnected global economy creates unprecedented business opportunities to market and sell intellectual property worldwide. Geographic borders present no impediment to international distribution channels. If the product cannot be immediately downloaded to a computer, it can be shipped and arrive by next day air. However, the same technology that benefits rights-holders and consumers also benefits intellectual property thieves seeking to make a fast, low-risk profit. In addition, trafficking in counterfeit merchandise also generates large profits.

4-98. The most egregious violators are large-scale criminal networks and transnational criminal organizations whose conduct threatens not only intellectual property owners but also the economy of nation-states. Because many violations of intellectual property rights involve no loss of tangible property and do not require direct contact with the rights-holder, the owner often does not even know that it is a victim for some time.

4-99. Intellectual property crimes can overlap with computer crimes, especially in the following areas:

– Unauthorized access of a computer to obtain information.

– Mail or wire fraud (can include the Internet).

– Devices to intercept communications.4-100. Unauthorized obtainment of information or electronic media covered by copyright, trademark, patent, or trade-secret designation robs the rights-holders of their ideas, inventions, and creative expressions. Such theft is facilitated by digital technologies and Internet file sharing networks.

4-101. Although fraud schemes can involve copyrighted works, it is not mail or wire fraud unless there is evidence of any misrepresentation or scheme to defraud. Mail and wire fraud may exist, even if the perpetrator tells his direct purchasers that his goods were counterfeit, as long as he and his direct purchasers intended to defraud the direct purchaser’s customers. Wire fraud can include the Internet.

4-102. Intellectual property crimes may involve intercepting and acquiring the contents of communications through the use of electronic, mechanical, or other devices. Criminals may then market the contents of an illegally intercepted communication, including intellectual property.