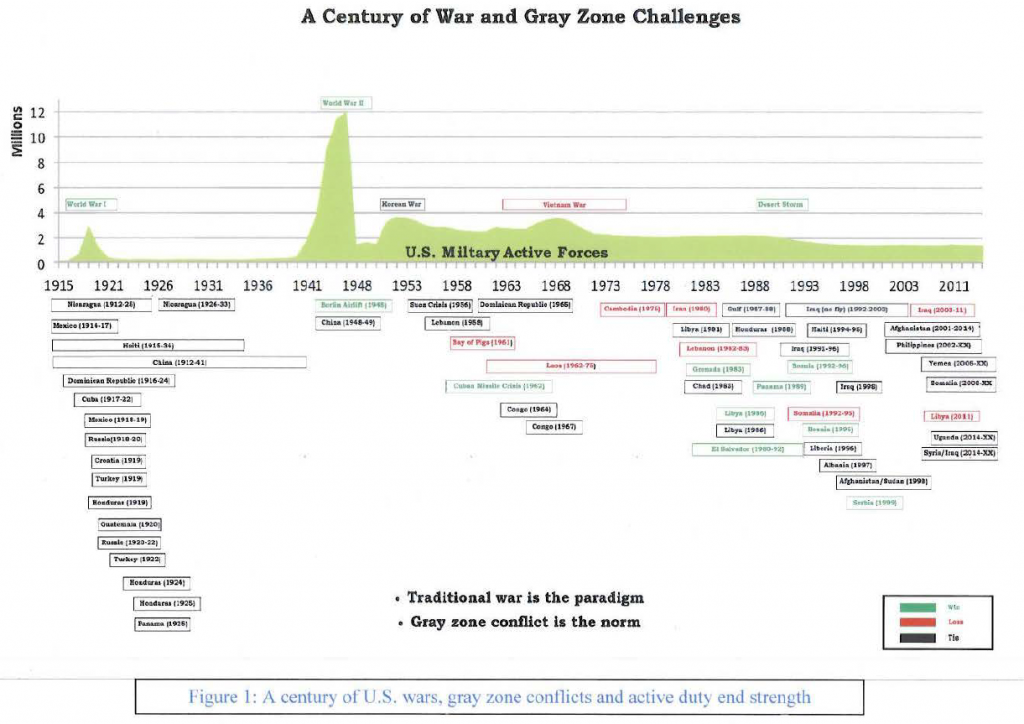

Gray zone security challenges, existing short of a formal state of war, present novel complications for U.S. policy and interests in the 21st century. We have well-developed vocabularies, doctrines and mental models to describe war and peace, but the numerous gray zone challenges in between defy easy categorization. For purposes of this paper, gray zone challenges are defined as competitive interactions among and within state and non-state actors that fall between the traditional war and peace duality. They are characterized by ambiguity about the nature of the conflict, opacity of the parties involved, or uncertainty about the relevant policy and legal frameworks.

Gray zone challenges can be understood as a pooling of diverse conflicts exhibiting common characteristics. Notably, combining these challenges does not imply a single solution, since each situation contains unique actors and aspects. Overall, gray zone challenges rise above normal, everyday peacetime geo-political competition and are aggressive, perspective-dependent, and ambiguous.

As the world’s leading superpower and de facto guarantor ofthe current world order, American national security interests span the globe and intersect with numerous circumstances fitting the definition of gray zone challenges. However, many of these challenges exist independent of U.S. agency or action and do not merit American involvement (e.g. civil conflicts in Africa). Accordingly, this paper acknowledges and briefly discusses the larger construct of gray zone challenges across the world, but it focuses on the United States’ national security interests and those gray zone challenges such as Russian actions in eastern Ukraine and Daesh (ISIS) that are relevant to America today.

…

Gray Zones Characteristics

Some level of aggression is a key determinant in shifting a challenge from the white zone of peacetime competition into the gray zone. The U.S. seeks to address disputes through diplomacy, but has always reserved the right to take military action to defend its interests, even acting upon that reservation despite multinational pressure to the contrary. We established laws, policies, authorities and mechanisms to arbitrate disagreements in peacetime, and Americans benefit greatly from an ordered world where all parties play by known rules. The post-World War II international system was established by and to the advantage of the United States and the West. A slew of state and non-state actors now aggressively oppose this Western-constructed international order, but in ways that fall short of recognized thresholds of traditional war. In simple terms, we understand war and peace and how to act during these instances, but there is a vast range of conflicts between these well-understood poles where we struggle to respond effectively.