The following report was released July 26, 2013 by the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security.

HOUSE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY MAJORITY STAFF REPORT ON THE NATIONAL NETWORK OF FUSION CENTERS

HOUSE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY MAJORITY STAFF REPORT ON THE NATIONAL NETWORK OF FUSION CENTERS

- 111 pages

- July 2013

- 4.4 MB

In the aftermath of the information sharing failures leading to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks that killed nearly 3,000 people in New York City, at the Pentagon, and in a Pennsylvania field, States and localities across the United States established what are known today as State and Major Urban Area Fusion Centers (fusion centers). Collectively known as the National Network of Fusion Centers (National Network), many of these – now numbering 78 – fusion centers are still in their infancy.

The Homeland has been attacked five times since 2001: the Little Rock Recruiting Station shooting (2009); the Fort Hood shooting (2009); the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 on Christmas Day (2009); the attempted car bombing in Times Square (2010), and the Boston Marathon bombings (2013). In the wake of these attacks, we have come to understand that homeland security, including counterterrorism efforts, must be a National responsibility – a true and equal partnership across all levels of government, and inclusive of the American people themselves. A top down, wholly Federal approach simply does not and cannot suffice. Fully integrating State and local law enforcement and emergency response providers as National mission partners requires a grassroots intelligence and analytic capability. Stakeholders rely upon fusion centers to provide that capability.

…

During the 112th Congress, then-Committee on Homeland Security (Committee) Chairman Peter T. King, currently the Chairman of the Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence, directed Committee Majority staff to conduct a comprehensive study of the National Network in an effort to understand current strengths and gaps and provide recommendations for improvement. This work continued into the 113th Congress under the additional direction of current Committee Chairman Michael T. McCaul. Over the course of nineteen months (January 2012-July 2013), the Committee logged 147 meeting hours during visits to 32 fusion centers, in addition to numerous briefings and discussions with various Federal partners, representatives of the National Fusion Center Association, and follow-up conversations with fusion center directors and personnel.

Summary of Findings

• The Committee strongly believes that the National Network is a National asset that needs to realize its full potential to help secure the Homeland. Based on the Committee’s long history of oversight of the fusion centers’ development, it appears that the National Network is on a path of continued growth, improvement, and increasing value to both the Federal Government and the fusion centers’ individual customers. In addition to significant numbers of State and local partners represented, site visits revealed over 20 different Federal offices and agencies with personnel assigned across the 32 visited fusion centers, suggesting that fusion centers provide value to a wide variety of Federal agencies.

• The strength of the National Network lies in individual fusion centers’ unique expertise; their independence from the Federal Government; and their ability to leverage the State and local perspective on behalf of the National homeland security mission, which includes counterterrorism. Formally standardizing all aspects of fusion center operations would be disadvantageous. Over the past three years, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) efforts have been targeted to assist fusion centers in developing plans, policies, and standard operating procedures. The goal has been to achieve capacity and standardized capability – namely the Critical Operational Capabilities – across the National Network, while allowing individually tailored processes for each fusion center. Although much work remains, these efforts appear to have improved consistency and standardization, and have helped to establish a common “language” across the National Network.

• The Federal Government should continue to facilitate and enable fusion center development in order to ensure that centers have the capacity necessary to fulfill their role as National mission partners. This must include continued improvements in information sharing. However, State and local stakeholders, including the fusion centers themselves, must take ownership and be a driving force behind much of the requisite growth moving forward. In order for the National Network to develop fully, a greater level of commonality and unified direction is necessary.

• The lack of a comprehensive State and locally-driven National Strategy for Fusion Centers reflecting the equities of fusion centers’ diverse stakeholders is a barrier to the National Network reaching its full potential. A comprehensive Federal Strategy for Fusion Centers is also necessary to explain how and why the Federal Government engages with fusion centers, guide Federal planning, serve as the foundation to develop additional performance and value-based metrics, and drive Federal resource allocation to fusion centers. The lack of these two strategies stands in the way of maximum efficiency, effectiveness, and the ability of the National Network to provide full benefit to the National homeland security mission.

• Thus far, fusion center metrics have primarily focused on measuring capacity and capability rather than “bang for the buck.” Due to the inherent difficulty in determining the success of prevention activities, stakeholders struggle with how to accurately, adequately, and tangibly measure the value of fusion centers to the National homeland security mission, and particularly the counterterrorism mission. Although great strides have been made, the current metrics – including the five performance measures included in the 2012 annual Fusion Center Assessment – are only a partial measure, and do not alone demonstrate overall success or failure of the National Network. Future metrics should reflect the values articulated in a comprehensive National Strategy for Fusion Centers and companion Federal Strategy for Fusion Centers. Further, there are not currently any tracking mechanisms in place to provide a complete picture, even quantitatively, of how fusion center-gathered information affects Federal terrorism or criminal cases or other homeland security mission areas. This is a significant gap that must be corrected in the short term in order to show the value of the National investment.

• Challenges remain across the National Network itself, particularly with the lack of individual fusion centers’ operational activities being universally inclusive of strategic counterterrorism threat analysis. Participation in the National Network should carry with it the expectation of National mission partnership, including the production of strategic counterterrorism threat analysis. Mature fusion centers utilize their analytic expertise, understanding of the nuances of their local environment, and unique information to look for potential ties to terrorism, in addition to fulfilling their other State, local, and homeland security missions. However, as a true National partner, fusion centers must fulfill their individual missions in a way that trains and requires analysts to view State and local crime with an eye toward strategic National counterterrorism and threat analysis.

• There should be continued enhancement and growth in the areas of analysis, Terrorism Liaison Officer programs, partnerships with first responders and public health officials, and Critical Infrastructure and Key Resources sectors.

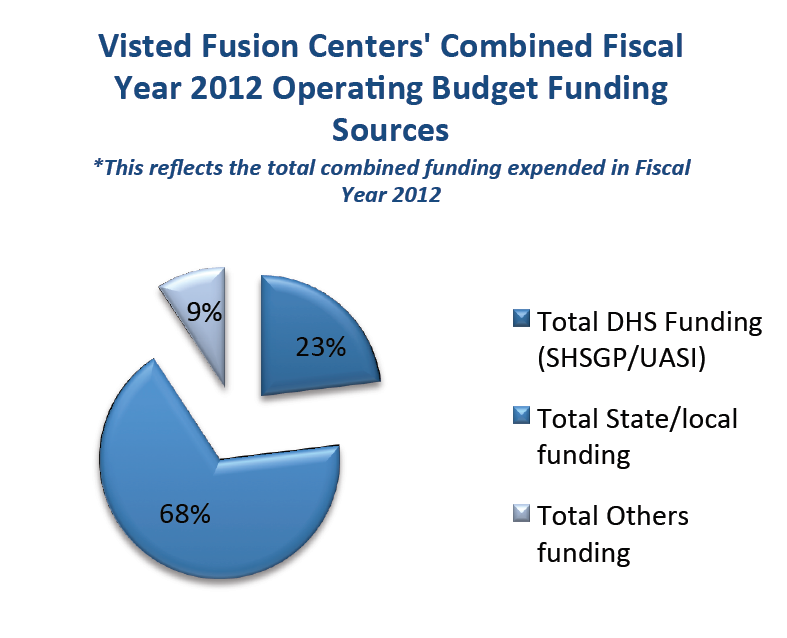

• Owned and operated by States and localities, the bulk of Federal investment in fusion centers is limited to funds subgranted to the fusion centers through the DHS preparedness grants, specifically the State Homeland Security Grant Program and the Urban Area Security Initiative, and through the deployment of computer systems, training, and personnel,primarily from DHS’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

• Stakeholders must undergo a thorough discussion to determine the next steps to ensure the National Network continues to develop as a partner in the National and Homeland Security Enterprises. Lack of action at this juncture could have a negative, and potentially debilitating impact on the National Network, which in turn could undermine homeland security.

Particularly in light of the current fiscal climate, the National Network is at a crossroads. Many fusion centers are struggling to maintain their operational tempo due to drastically changing annual budgets. As a result, some fusion centers are facing the possibility of closing or having to make significant changes to their staffing or operations. Fusion center directors consistently noted that if Federal grant funding were to disappear their individual fusion center would likely remain, but its focus would turn inward toward exclusively State and local mission needs. This would reduce those fusion centers’ potential value to the National homeland security mission, possibly leaving the Homeland less secure.

…