Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

- 74 pages

- January 2010

This report details key findings of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s (FinCEN) assessment of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) filed from May 2, 2007, through April 30, 2008, by insurance companies and includes some preliminary observations about SARs filed from May 2008 through October 2009. It compares the results through April 2008 with a similar study of the first year of required reporting by segments of the insurance industry (May 2, 2006, through May 1, 2007). FinCEN analyzed insurance filings to identify typologies, patterns, and trends related to filing volume, filer location, subject details, characterizations of suspicious activities, insurance products, and other relevant information. Analysis includes summaries of SAR narratives identifying reported money laundering risks and vulnerabilities. In identifying potential trends, FinCEN reached out to representatives of the Bank Secrecy Act Advisory Group (BSAAG) to better understand what the industry is seeing with regard to these trends. That information is summarized in the Significant Findings section.

This report also offers insight into the quality of the SAR reporting. SAR narratives should make available clear, concise, and valuable information to law enforcement investigators. Providing feedback to filers promotes better information for law enforcement and helps shape future industry compliance efforts. In turn, insurers covered by Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) anti-money laundering requirements should ensure that their compliance programs enable them to detect and report the range of suspicious activities that they may encounter.

…

FinCEN’s assessment of SARs filed by insurance companies in the one-year period from May 2, 2007, through April 30, 2008, finds that most filers are primarily reporting on various suspicious payment methods. Additionally, while SAR filings almost doubled in the second year of mandatory reporting, from 641 to 1,276 SARs, virtually half of the filings—628 reports—came from the subsidiaries of two parent

companies. With a few exceptions, the quality of SARs provided by insurance companies continues to be good. However, the filing patterns, while not conclusive, may be an indication of significantly divergent approaches to meeting SAR filing requirements, with some institutions not yet demonstrating the breadth of focus that others have incorporated into their compliance programs.Several types of suspicious activity were largely reported by one or two insurance companies, and rarely reported by the rest. For example, 48 of the 62 SARs describing early or excessive borrowing were filed by subsidiaries of two parent companies; however, the five leading SAR filers combined for only six such SARs. Likewise, 42 of the 65 reports of subjects making large withdrawals despite penalties came from

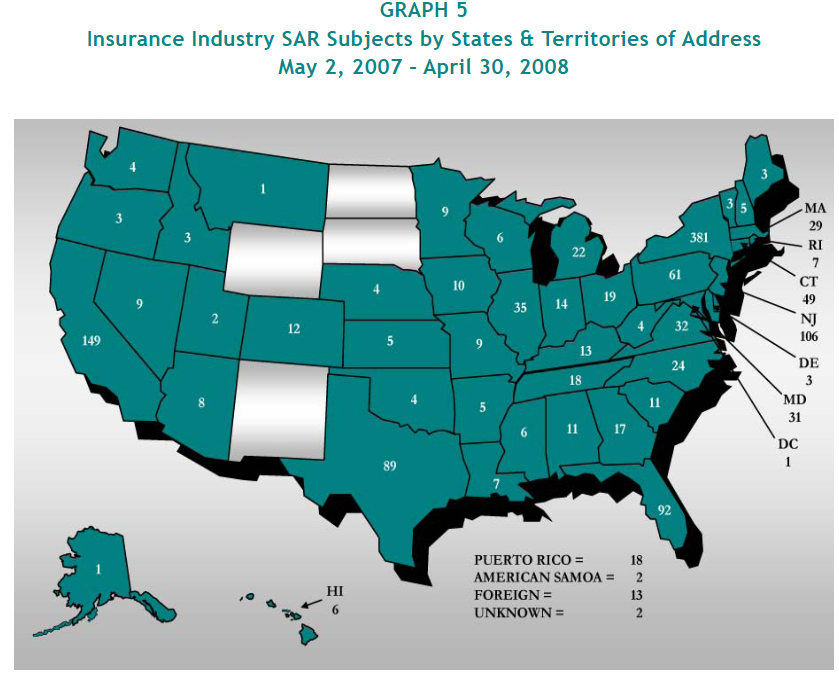

just four parent companies, while the five leading SAR filers reported only three cases. This may be a reflection of the different products offered by insurance companies as well as the different markets in which they conduct their business. It may also, however, indicate significant divergence in the way some insurance companies are approaching SAR filing requirements. Notwithstanding these observations, the three most cited activity characterizations of each of the four top filing parent companies—excluding “Structuring/Money Laundering”—constituted over 90 percent of the SARs of each parent.The top reported states based on subject location were New York, California, New Jersey, Florida and Texas. Policy holders and annuity owners continue to be the most reported subjects in the SAR filings for insurance products, and while most were individual subjects, business entities, trusts and retirement plans were also reported as subjects. Ninety-four SARs named insurance insiders as subjects,

primarily agents and brokers. Gatekeepers4, whose occupations may give them direct responsibility to manage money for others, such as accountants or lawyers, accounted for a total of 242 SARs.

The second year of insurance SAR filings revealed some potential trends in illicit activity. Some of the typologies evidenced in the narratives appeared very similar to classical examples of the money laundering stages of layering and integration.5 For example, as seen with the first year of mandatory reporting, many SARs again reported subjects using multiple cash equivalents (e.g., cashier’s checks and money orders) from different banks and money services businesses to make insurance policy or annuity premium payments. Fewer reports cited customers willing to incur significant penalties for surrendering their annuity policy early. Approximately 43 percent (545 of the 1,276 SARs) identified one or more business owners or self-employed individuals as subjects. The rate of increase in insurance company SAR filings have slowed in the period following this study (May, 2008 – October, 2009). During this period, 107 distinct filers submitted 2,109 SARs, 17 companies averaged at least 1 report per month, and 6 filers surpassed 100 reports. The highest volume by any one filer during this period was 281 SARs. Self-designated SAR-ICs increased dramatically in the third year of mandatory filings by the insurance industry.…