CRS Report

CRS Report

- R41215

- 38 pages

- April 30, 2010

Drug trafficking is viewed as a primary threat to citizen security and U.S. interests in Latin America and the Caribbean despite decades of anti-drug efforts by the United States and partner governments. The production and trafficking of popular illicit drugs—cocaine, marijuana, opiates, and methamphetamine—generates a multi-billion dollar black market in which Latin American criminal and terrorist organizations thrive. These groups challenge state authority in source and transit countries where governments are often fragile and easily corrupted. Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) largely control the U.S. illicit drug market and have been identified by the U.S. Department of Justice as the “greatest organized crime threat to the United States.” Drug trafficking-related crime and violence in the region has escalated in recent years, raising the drug issue to the forefront of U.S. foreign policy concerns.

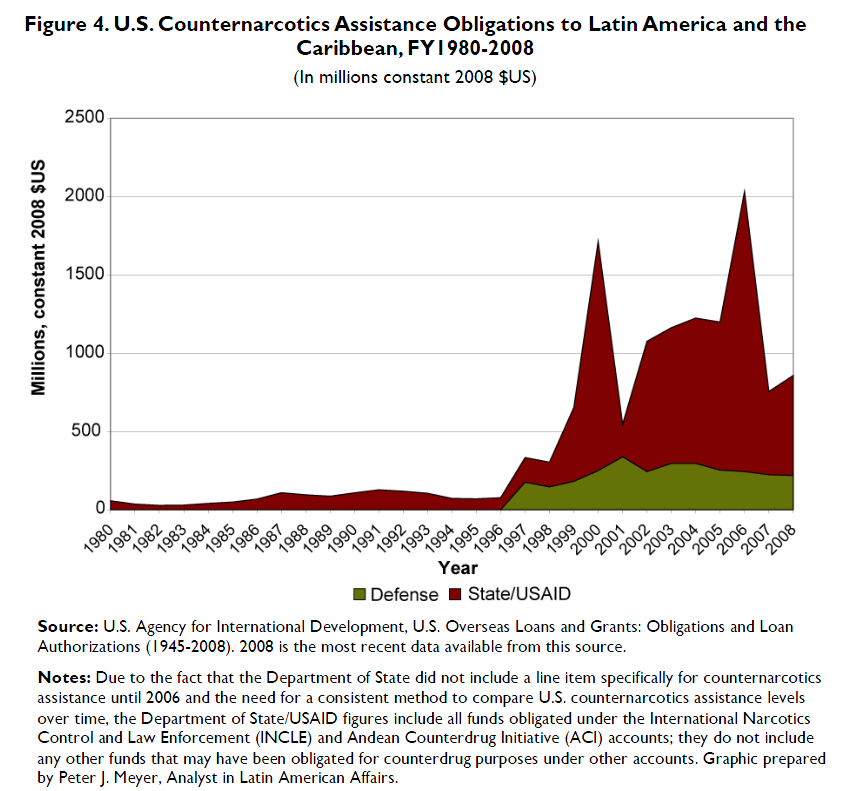

Since the mid-1970s, the U.S. government has invested billions of dollars in anti-drug assistance

programs aimed at reducing the flow of Latin American-sourced illicit drugs to the United States.

Most of these programs have emphasized supply reduction tools, particularly drug crop

eradication and interdiction of illicit narcotics, and have been designed on a bilateral or subregional

level. Many would argue that the results of U.S.-led drug control efforts have been

mixed. Temporary successes in one country or sub-region have often led traffickers to alter their

cultivation patterns, production techniques, and trafficking routes and methods in order to avoid

detection. As a result of this so-called “balloon effect,” efforts have done little to reduce the

overall availability of illicit drugs in the United States. In addition, some observers assert that

certain mainstays of U.S.-funded counterdrug programs, particularly aerial spraying to eradicate

drug crops, have had unintended social and economic consequences.The Obama Administration has continued U.S. support for Plan Colombia and the Mérida

Initiative, but is gradually broadening the focus of those aid packages to address the societal and

institutional effects of the drug trade and related criminality and violence, rather than mainly

funding supply control efforts. Newer programs like the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative

(CBSI) include more of an emphasis on rule of law, anti-corruption, and community and youth

development programs. In order to complement these international efforts, President Obama and

his top advisers have acknowledged the role that U.S. drug demand has played in fueling the drug

trade in the region and requested increased funding for prevention and treatment programs.

The 111th Congress has influenced U.S. drug control policy in Latin America by appropriating

certain types and levels of funding for counterdrug assistance programs in P.L. 111-8, P.L. 111-32,

and P.L. 111-117. Congress has also conditioned the provision of antidrug funding on the basis of

human rights and other reporting requirements. It has sought to ensure that counterdrug programs

are implemented in tandem with judicial reform, anti-corruption, and human rights programs.

Several bills address counternarcotics issues in the region, including House-passed H.R. 2410

(Berman), House-passed H.R. 2134 (Engel) and S. 3172 (Menendez). Congress has been active in

evaluating drug assistance programs through multiple oversight hearings.…