An entirely blank page from the redacted version of the DoJ's Online Investigative Principles for Federal Law Enforcement Agents appears on the left. A complete, unredacted copy of the page occurs on the right.

Public Intelligence

In 1999 the Department of Justice convened a working group to discuss the increasingly technological makeup of criminal organizations and the challenges law enforcement face when conducting online investigations. The Online Investigations Working Group included members of the FBI, Treasury, Secret Service, IRS, ATF, Air Force and even NASA who worked to produce a series of general principles governing the legality of online investigative practices. The working group came up with eleven principles governing everything from basic information gathering to undercover operations and wrote a final report titled “Online Investigative Principles for Federal Law Enforcement Agents” that detailed the group’s findings. Though it was originally marked as “Sensitive Law Enforcement Information,” a significant portion of the document was released to the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) in 2004. However, several very significant portions of the document that discuss online undercover operations were released in a heavily redacted form. These sections are highly relevant to understanding law enforcement’s pursuit of the hacktivist group Anonymous and the recent case of LulzSec leader “Sabu” who operated for nearly six months as a FBI informant after his arrest in June 2011.

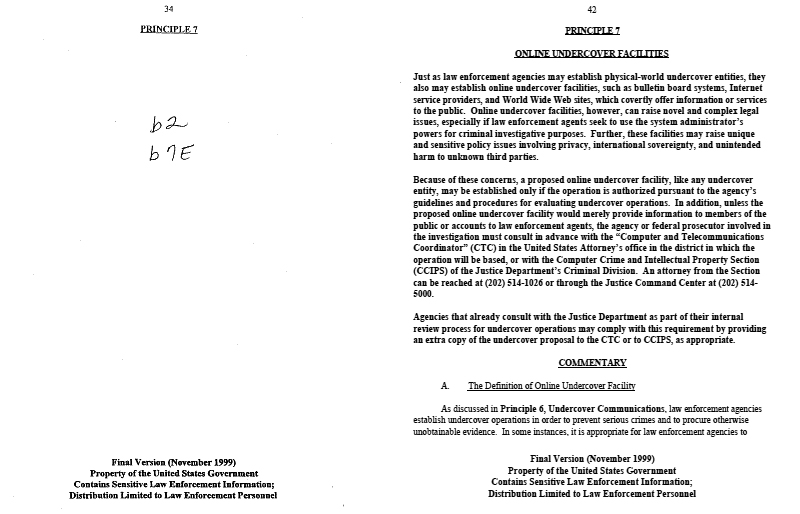

Though it was written over a decade ago, the principles described in the DoJ’s guide for federal agents offer tremendous insight into the legal reasoning behind many tactics used by law enforcement to gather evidence in online settings. These tactics can range from the basic, such as using internet search tools or looking up an IP address, to the more advanced, like creating undercover online identities and websites to gather incriminating information. When the document was first released to EPIC in 2004, two sections were entirely redacted for the reason that they “would disclose techniques and procedures for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions.” The first section covered Principle 7 of online investigations “Online Undercover Facilities” which describes how “just as law enforcement agencies may establish physical-world undercover entities, they also may establish online undercover facilities, such as bulletin board systems, Internet service providers, and World Wide Web sites, which covertly offer information or services to the public.” The second section removed from the document discussed Principle 9 “Appropriating Online Identities” which occurs when “a law enforcement agent electronically communicates with others by deliberately assuming the known online identity (such as the username) of a real person, without obtaining that person’s consent.”

The document’s description of online undercover facilities states that federal agents may operate websites, web-based services and even ISPs either directly or indirectly in order to obtain evidence in a criminal case. An example of such an operation is provided:

As part of a project to identify and prosecute computer criminals, a law enforcement agency considers a proposal to operate a World Wide Web site with information about and computer programs for hacking, links to other hacker sites, and a facility to allow people who access the site to discuss hacking techniques. The proposal would allow the law enforcement agents running the site to track all visitors, and monitor all communications among the users. Because this proposal would establish an online undercover facility that would do more than just provide information or a means to contact agents, the consultation requirement applies to this proposal.

This means that if you are the subject of a high-level criminal investigation, online services that you use, such as a VPN or server provider, could in fact be part of an elaborate law enforcement operation and access to your private user information may have been gained either surreptitiously or through direct consent of the service’s legitimate operators. In addition to setting up false web facilities, federal agents may also seize someone’s “online identity” to communicate with others and gather evidence while representing themselves as the owner of the seized identity. The recent case of LulzSec leader/FBI informant Sabu is actually different than this because Hector Xavier Monsegur, the individual who used the name Sabu and operated its associated Twitter account, gave law enforcement permission to use his identity to gain evidence from other users. This method is also covered in the document under Principle 8 “Communicating Through the Online Identity of a Cooperating Witness, With Consent.”