The following report from the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime was released February 7, 2013.

CORRUPTION IN AFGHANISTAN: RECENT PATTERNS AND TRENDS

- 40 pages

- December 2012

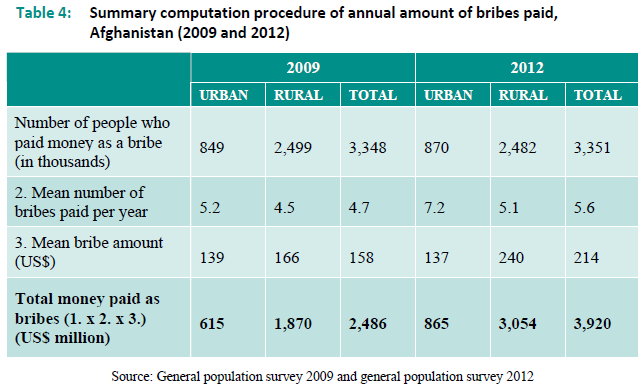

The large-scale population survey on the extent of bribery and four sector-specific integrity surveys of public officials undertaken by UNODC and the Government of Afghanistan in 2011/2012 reveal that the delivery of public services remains severely affected by bribery in Afghanistan and that bribery has a major impact on the country’s economy. In 2012, half of Afghan citizens paid a bribe while requesting a public service and the total cost of bribes paid to public officials amounted to US$ 3.9 billion. This corresponds to an increase of 40 per cent in real terms between 2009 and 2012, while the ratio of bribery cost to GDP remained relatively constant (23 per cent in 2009; 20 per cent in 2012).

While corruption is seen by Afghans as one of the most urgent challenges facing their country, it seems to be increasingly embedded in social practices, with patronage and bribery being an acceptable part of day-to-day life. For example, 68 per cent of citizens interviewed in 2012 considered it acceptable for a civil servant to top up a low salary by accepting small bribes from service users (as opposed to 42 per cent in 2009). Similarly, 67 per cent of citizens considered it sometimes acceptable for a civil servant to be recruited on the basis of family ties and friendship networks (up from 42 per cent in 2009).

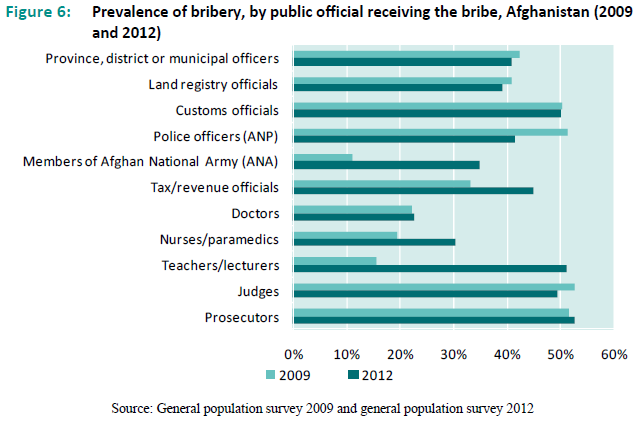

Since 2009 Afghanistan has made some tangible progress in reducing the level of corruption in the public sector. While 59 per cent of the adult population had to pay at least one bribe to a public official in 2009, 50 per cent had to do so in 2012, and whereas 52 per cent of the population paid a bribe to a police officer in 2009, 42 per cent did so in 2012.

However, worrying trends have also emerged in the past three years: the frequency of bribery has increased from 4.7 bribes to 5.6 bribes per bribe-payer and the average cost of a bribe has risen from US$ 158 to US$ 214, a 29 per cent increase in real terms. Education has emerged as one of the sectors most vulnerable to corruption, with the percentage of those paying a bribe to a teacher jumping from 16 per cent in 2009 to 51 per cent in 2012. In general, there has been no major change in the level of corruption observed in the judiciary, customs service and local authorities, which remained high in 2012, as in 2009.

Although with a different intensity, bribery not only affects the public sector but also nonpublic sector entities in Afghanistan. Nearly 30 per cent of Afghan citizens paid a bribe when requesting a service from individuals not employed in the public sector of Afghanistan in 2012, as opposed to the 50 per cent who paid bribes to public officials. The national economic impact of non-governmental bribery is also lower, with an estimated total cost of US$ 600 million, some 15 per cent of the estimated US$ 3.9 billion paid to the public sector.

Significant variations in the distribution of these two types of bribery also exist across Afghanistan. The public sector is most affected by bribery in the Western (where 71 per cent of the population accessing public services experienced bribery) and North-Eastern Regions (60 per cent), while it is least affected in the Southern (40 per cent) and Central (39 per cent) Regions. On the other hand, local individuals and entities not employed in the public sector of Afghanistan, such as village elders, Mullahs and Taliban groups, are more involved in bribery in the Southern region (nearly 60 per cent of those who had contact with such individuals).

The analysis of specific forms of bribery in four different sectors of the public administration in Afghanistan (police, local government, judiciary and education), by means of the integrity surveys, indicates that bribery takes place for different reasons in different circumstances. In most cases bribes are paid in order to obtain better or faster services, while in others bribes are offered to influence deliberations and actions such as police activities and judicial decisions, thereby eroding the rule of law and trust in institutions. For example, 24 per cent of cases in which bribes were offered to the police were related to the release of imprisoned suspects or to avoid imprisonment.

The data show that for every five Afghan citizens who paid at least one bribe in the 12 months prior to the survey, there was one who refused to do so mainly due to a lack of financial resources. This means that the use of bribery in the public sector affects the capacity of the Afghan population to access necessary services, and that — as they are more likely to accept the payment of bribes — higher income households can ensure better accessibility to, and a higher quality of, public services than households with lower incomes. Conversely, citizens with lower incomes are more likely to turn down requests for bribes, which effectively prices them out of the “market” for public services and makes them less likely to receive fair service delivery.

Recruitment in the public sector has shown itself to be an area of concern in Afghanistan as it is largely based on bribes or patronage. About 80 per cent of citizens with a family member recruited into the civil service in the last three years declared that the family member in question received some form of assistance or paid a bribe to be recruited. Civil servants in the four sectors covered in the integrity surveys also acknowledged that assistance with recruitment is widespread. For example, some 50 per cent of police, local government staff and school teachers indicated that they received assistance during their recruitment.

When it comes to reporting bribery, 22 per cent of those who paid a bribe in 2012 reported the incident to authorities such as the police (one third), the public prosecutor’s office and the High Office of Oversight and Anti-Corruption (one fifth each). While the bribery reporting rate in Afghanistan seems to be relatively high by international comparison, it is not clear if the reporting declared in the survey took place in a formal setting since it rarely led to effective results. Indeed, less than a fifth of cases reported to the authorities resulted in a formal procedure and the majority of claims did not lead to any type follow up.

…