The Asymmetric Warfare Group (AWG) sponsored the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) to analyze the phenomenon of Russian private military companies (PMCs), the scenarios under which they would matter to U.S. Army maneuver commanders, and whether they constitute a unique threat to U.S. and partner forces.

The primary audience for this analysis is U.S. Army maneuver commanders and their staffs, but the findings and insights should also be useful for anyone in the U.S. national security and defense communities concerned with asymmetric operations of the Russian Federation around the world. First, this analysis presents key findings from deep-dive research and analysis on Russian PMCs presented in the appendix. It addresses their uses, equipment, training, personnel, state involvement, legal issues, and other related topics. Second, these findings are used to inform an analytical model to explore the operational challenges and considerations Russian PMCs could present to U.S. Army maneuver commanders.

Key Findings

Bottom Line Up Front: Russian PMCs are used as a force multiplier to achieve objectives for both government and Russia-aligned private interests while minimizing both political and military costs. While Moscow continues to see the use of Russian PMCs as beneficial, their use also presents several vulnerabilities that present both operational and strategic risks to Russian Federation objectives.

Friendly Regime Support: Russian lawmakers view Russian PMCs as an instrument to prop up friendly regimes under threat of collapse or ouster. Russian PMCs operate:

• Alongside and embedded with friendly state militaries.

• With non-state armed groups in offensive combat operations.

Offensive Role: While also used for support tasks more typical of military and security contractors, Russian PMCs have had a pronounced role in offensive combat operations.

Shifting Control: The command and control (C2) of Russian PMCs is not consistent in all operational contexts.

• Sometimes Russian PMCs fall under the C2 of the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) or Russian intelligence agencies.

• At other times, PMCs fall under the C2 of partner governments or aligned private interests.

Inconsistent Capabilities: The quality of personnel and materiel enabling Russian PMCs is inconsistent. Russian PMC capabilities in personnel, training, and equipment appear to be greater when a PMC is closely aligned with state support from the Russian MoD.

Informal by Design: Despite legislative efforts to legalize PMCs, Russian law continues to formally outlaw their creation and bars individuals from joining them under anti-mercenary laws. However, Russian leaders use this legal prohibition to strictly control some PMCs (e.g., the selective arrest of PMCs who might present domestic security or political risks), not to prevent PMCs from operating.

Vulnerabilities: The use of Russian PMCs presents new operational and strategic risks to Moscow. Morale in Russian PMC units in high-risk missions appears delicate. Although their use provides political protection from the optics of high Russian MoD casualties, both Russian PMC casualties and their return home create novel political and domestic security risks. Their use also complicates internal regime politics in Moscow, creating competition between the MoD and private equities that can jeopardize operations (see the appendix: Syria). Finally, the ambiguity of operational control and decision making over Russian PMCs opens Moscow up to the risk of being held responsible by the international community for actions taken by Russian PMCs under the command of other interests.

Operational Challenges and Considerations Presented by Russian PMCs

Bottom Line Up Front: Russian PMCs do not pose a unique tactical threat—other state and non-state actors are similarly capable. However:

• PMCs can operate across the conflict continuum and present the United States with dilemmas at all levels of war.

• Challenges Russian PMCs could pose in noncombatant evacuation operations (NEOs) and peacekeeping operations (PKOs) deserve careful consideration

Most Dangerous Scenario: The most dangerous scenario involving a Russian PMC is one where a U.S. Army brigade could encounter a state-supported, battalion tactical group (BTG)-like entity with advanced weapons, cutting-edge enabler technologies, and expertise:

• With a high level of Russian state support, a Russian PMC in Syria was able to function as a quasi-BTG; it conducted basic combined arms operations with infantry, armor, and artillery.

• With the aid of Russian support and forces, separatists in eastern Ukraine conducted combined arms operations and was highly proficient at enabling integration, particularly information operations (IO), electronic warfare (EW), and unmanned aerial systems (UAS).

Most Likely Scenarios: Russian state-supported PMC operations aimed at disrupting U.S. operations during crisis response or limited contingency operations. PMCs might execute the following:

• Occupy potential evacuation sites or other key terrain during a NEO.

• Ally with local actors in PKO to provide weapons and training to groups opposed to U.S. actions.

• Provide other forms of support, including intelligence and maintaining influence in a given area.

Other Potential Scenarios: Less severe scenarios exist where Russian PMCs could seek to compete with and undermine U.S. influence with local authorities and civilians.

…

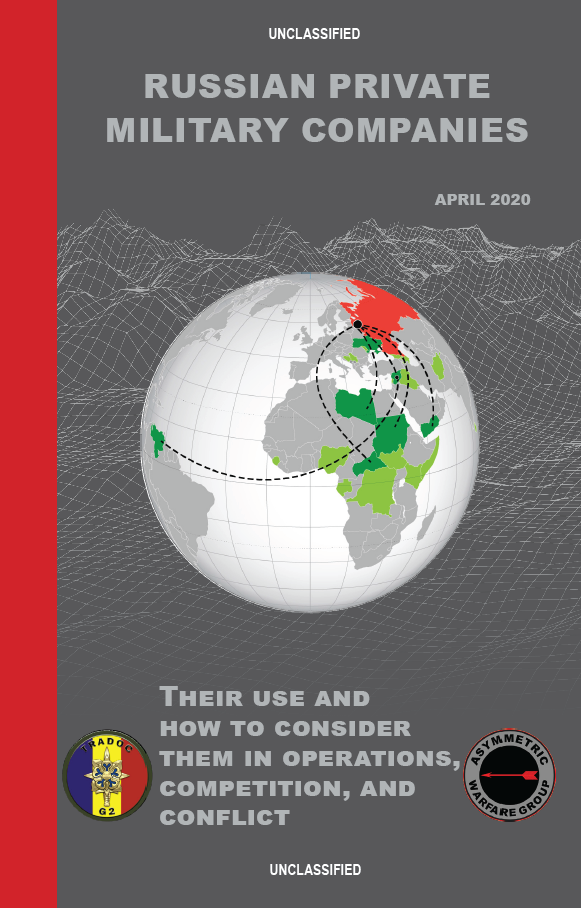

Russian PMCs are known, alleged, and suspected of being present and operating in numerous countries across eastern and central Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere. This appendix details available information concerning Russian PMC activities in known or suspected AOs to inform the analysis contained in the body of this report.

Syria, Ukraine, the CAR, and Sudan are discussed in depth, detailing the uses and other attributes of Russian PMCs in each AO. Other AOs discussed at length are Yemen, Libya, Nigeria, and Venezuela. Other countries where Russian PMCs are alleged to have operated are also mentioned and briefly discussed.

…

Overt Intervention in Syria

The advent of the Russian Federation’s formal military involvement in September 2015 initiated significant growth in the offensive use of Russian PMCs in Syria and shined a brighter light on the operations of Wagner, which served a role in Ukraine up until that point that was harder for observers to distinguish from other actors in the conflict. Russian PMCs were active in Syria well before Russia’s formal intervention—Wagner since fall 2014 or earlier,190 and the Slavonic Corps in 2013. However, the formal use of force brought an influx of Russian PMC personnel and initiated a period punctuated by several battles where Russian PMCs played a significant role—primarily Wagner, at times going by the name “OSM” according to some press reports.

…

In late 2013, Ukraine was expected to sign an association agreement with the European Union (EU). However, this would have precluded the country from membership in the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), so Moscow imposed escalating economic reprisals and threats on Kyiv, to the point that Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych announced a surprise reversal. The announcement sparked the Euromaidan movement—a long series of pro-Western, anti-Russian protests and clashes from late 2013 to early 2014 in Kyiv and across western Ukraine—which, despite efforts by Moscow, removed Yanukovych from office. Russia responded with military operations to invade and annex the Crimean Peninsula and support separatist forces in eastern Ukraine.

Alleged Use on the Crimean Peninsula

In late February 2014, Russian special forces personnel in unmarked uniforms appeared in Crimea and took control of certain government, airport, and other facilities. Euphemistically referred to as “polite people” or “little green men,” these officially unattributed forces operated alongside other military formations to immobilize Ukrainian forces and eventually take full control of the peninsula. Several open source reports allege that RussianPMCs participated in the operations leading to the annexation of Crimea (specifically an early iteration of Wagner that was at the time an informal grouping of Slavonic Corps remnants with locals and others). Nevertheless, the extent or veracity of a Russian PMC role in the invasion of Crimea is not confirmed, and there appears to be no direct evidence available to verify these claims. Russian Cossack units, however, played an overt role in the occupation as fighting forces, guards at checkpoints, and street enforcement to suppress protests.

…

There are several other countries where Russian PMCs are purported to be present and operating in some capacity. However, information concerning their uses, objectives, and other details is scarce. Additionally, differentiating whether such companies are operating as PSCs in the open market for force, or if they are fulfilling any Russian Federation foreign policy or security objectives, is unclear.