The Domestic Operational Law (DOPLAW) Handbook for judge advocates is a product of the Center for Law and Military Operations (CLAMO). The content is derived from statutes, Executive Orders and Directives, national policy, DoD Directives and Instructions, joint publications, service regulations, field manuals, as well as lessons learned by judge advocates and other practitioners throughout Federal and State government. This edition includes substantial revisions. It incorporates new guidance set forth in Department of Defense Directive 3025.18 (Defense Support of Civil Authorities), Department of Defense Instruction 3025.21 (Defense Support of Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies), numerous new National Planning Framework documents, and many other recently updated publications. It provides amplifying information on wildfire response, emergency mutual assistance compacts, the role of the National Guard and Army units in domestic response, and provides valuable lessons learned from major disasters such as Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

The Handbook is designed to serve as a working reference and training tool for judge advocates; however, it is not a substitute for independent research. With the exception of footnoted doctrinal material, the information contained in this Handbook is not doctrine. Judge advocates advising in this area of the law should monitor developments in domestic operations closely as the landscape continues to evolve. Further, the information and examples provided in this Handbook are advisory only. The term “State” is frequently used throughout this Handbook, and collectively refers to the 50 States, Guam, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, and the District of Columbia. The same is often referred to as “the 54 States and territories.” Finally, the content and opinions expressed in this Handbook do not represent the official position of the U.S. Army or the other services, the National Guard Bureau, the Office of The Judge Advocate General, The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, or any other government agency.

…

A Dual Status Commander maintains a commission in both a Title 10 and Title 32 capacity which helps to unify the effort of the Federal and National Guard personnel involved in the response to a major disaster or emergency. The National Defense Authorization Act for 201261 stated that when Federal forces and the National Guard are employed simultaneously in support of civil authorities,appointment of a Dual Status Commander should be the usual and customary command and control arrangement. This includes Stafford Act major disaster and emergency response missions. The use of Dual Status Commanders is becoming more common for incident response, and they have been used for planned and special events since 2004. Dual Status Commanders receive orders from both the State and Federal chains of command, and thus serve as a vital link between the two. Dual Status Commanders can be appointed in one of two ways. First, under 32 U.S.C. § 315, an active duty Army or Air Force officer may be detailed to the Army or Air National Guard of a State. Second, under 32 U.S.C. § 325, a member of a State’s Army or Air National Guard may be ordered to active duty. Regardless of method of appointment, the Secretary of Defense must authorize the dual status, and the Governor of the effected State must consent.

…

…

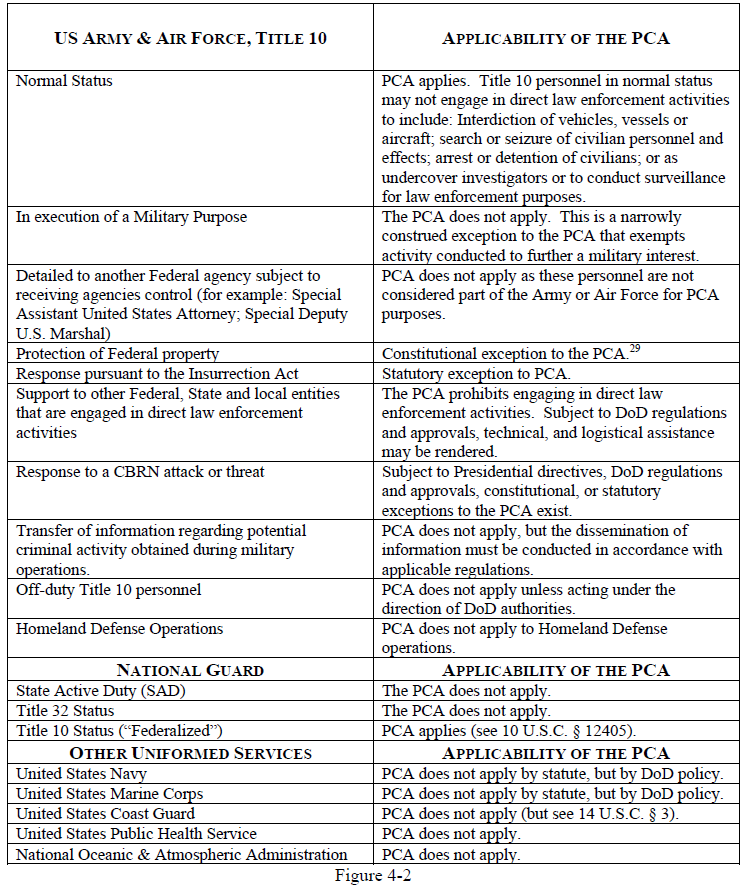

c. Participation of DoD Personnel in Civilian Law Enforcement Activities

The Federal courts have enunciated three tests to determine whether the use of military personnel violates the PCA. If any one of these three tests is met, the assistance may be considered a violation of the PCA.

- The first test is whether the actions of military personnel are “active” or “passive.” Only the active, or direct, use of military personnel to enforce the laws is a violation of the PCA.

- The second test is whether the use of military personnel pervades the activities of civilian law enforcement officials. Under this test, military personnel must fully subsume the role of civilian law enforcement officials.

- The third test is whether the military personnel subjected citizens to the exercise of military power that was regulatory, proscriptive, or compulsory in nature. A power “regulatory in nature” is one which controls or directs. A power “proscriptive in nature” is one that prohibits or condemns. A power “compulsory in nature” is one that exerts some coercive force. Note that under DoDD 3025.21, Immediate Response Authority may not be used when it may subject civilians to military power that is “regulatory, prescriptive, proscriptive, or compulsory.” Thus, Immediate Response Authority may not be used to circumvent the PCA.

…

(iii) Civil Disturbance Statutes

The third type of permitted direct assistance by military forces to civilian law enforcement is action taken pursuant to DoD responsibilities under the Insurrection Act, 10 U.S.C. §§ 251-255. This statute contains express exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act that allow for the use of military forces to repel insurgency, domestic violence, or conspiracy that hinders the execution of State or Federal law in specified circumstances. Actions under this authority are governed by DoDD 3025.21. The Insurrection Act permits the President to use the armed forces to enforce the law when:

- There is an insurrection within a State, and the State legislature (or Governor if the legislature cannot be convened) requests assistance from the President;

- A rebellion makes it impracticable to enforce the Federal law through ordinary judicial proceedings;

- An insurrection or domestic violence opposes or obstructs Federal law, or so hinders the enforcement of Federal or State laws that residents of that State are deprived of their constitutional rights and the State is unable or unwilling to protect these rights.

10 U.S.C. § 254 requires the President to issue a proclamation ordering the insurgents to disperse within a certain time before use of the military to enforce the laws. The President issued such a proclamation during the Los Angeles riots in 1992.

(iv) Other Authority

There are several statutes and authorities, other than the Insurrection Act, that allow for direct DoD participation in civil law enforcement.64 They permit direct military participation in civilian law enforcement, subject to the limitations within each respective statute. This section does not contain detailed guidance; therefore, specific statutes and other references must be consulted before determining whether military participation is permissible. A brief listing of these statutes includes:

- Prohibited transactions involving nuclear material (18 U.S.C. § 831)

- Emergency situations involving chemical or biological weapons of mass destruction (10 U.S.C. § 282) (see also 10 U.S.C. §§ 175a, 229E and 233E which authorizes the Attorney General or other DOJ official to request SECDEF to provide assistance under 10 U.S.C. § 282)

- Assistance in the case of crimes against foreign officials, official guests of the United States, and other internationally protected persons (18 U.S.C. §§ 112, 1116)

- Protection of the President, Vice President, and other designated dignitaries (18 U.S.C. § 1751 and the Presidential Protection Assistance Act of 1976)

- Assistance in the case of crimes against members of Congress (18 U.S.C. § 351)

- Execution of quarantine and certain health laws (42 U.S.C. § 97)

- Protection of national parks and certain other Federal lands (16 U.S.C. §§ 23, 78, 593)

- Enforcement of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery and Conservation Management Act (16 U.S.C. § 1861(a))

- Actions taken in support of the neutrality laws (22 U.S.C. §§ 408, 461–462)

- Removal of persons unlawfully present on Indian lands (25 U.S.C. § 180)

- Execution of certain warrants relating to enforcement of specified civil rights laws (42 U.S.C. § 1989)

- Removal of unlawful enclosures from public lands (43 U.S.C. § 1065)

- Protection of the rights of a discoverer of a guano island (48 U.S.C. § 1418)

- Support of territorial Governors if a civil disorder occurs (48 U.S.C. §§ 1422, 1591)

- Actions in support of certain customs laws (50 U.S.C. § 220)

- Actions taken to provide search and rescue support domestically under the authorities provided in the National Search and Rescue Plan

…

Cyber operations are not the future. They are now. The National Guard faces the same constraints in cyberspace as in the traditional kinetic realm. However, cyberspace presents some unique challenges. For instance, most military equipment is not governed by restrictive licensing agreements. However, software-licensing agreements may restrict who may use a cyber-tool kit and how that kit may be used. Additionally, cyberspace activities are generally not linear in nature. For example, one computer does not normally interact directly with another computer. Rather, the data is transferred through multiple routers and servers, all of which may not be in the same town, State or even country. As a result, actions intended to have a domestic effect in cyberspace could have international consequences. Additionally, attribution in cyberspace is not as clear as it is in the kinetic realm. What may appear to be an action taken by a local resident could very well be an action orchestrated by a foreign actor. This complex and evolving battle space requires legal practitioners to have both a basic understanding of how the cyberspace works as well as the laws and policies governing those actions.