In 2017 there were 30 separate active shootings in the United States, the largest number ever recorded by the FBI during a one-year period.1 With so many attacks occurring, it can become easy to believe that nothing can stop an active shooter determined to commit violence. “The offender just snapped” and “There’s no way that anyone could have seen this coming” are common reactions that can fuel a collective sense of a “new normal,” one punctuated by a sense of hopelessness and helplessness. Faced with so many tragedies, society routinely wrestles with a fundamental question: can anything be done to prevent attacks on our loved ones, our children, our schools, our churches, concerts, and communities?

There is cause for hope because there is something that can be done. In the weeks and months before an attack, many active shooters engage in behaviors that may signal impending violence. While some of these behaviors are intentionally concealed, others are observable and — if recognized and reported — may lead to a disruption prior to an attack. Unfortunately, well-meaning bystanders (often friends and family members of the active shooter) may struggle to appropriately categorize the observed behavior as malevolent. They may even resist taking action to report for fear of erroneously labeling a friend or family member as a potential killer. Once reported to law enforcement, those in authority may also struggle to decide how best to assess and intervene, particularly if no crime has yet been committed.

By articulating the concrete, observable pre-attack behaviors of many active shooters, the FBI hopes to make these warning signs more visible and easily identifiable. This information is intended to be used not only by law enforcement officials, mental health care practitioners, and threat assessment professionals, but also by parents, friends, teachers, employers and anyone who suspects that a person is moving towards violence.

…

Key Findings of the Phase II Study

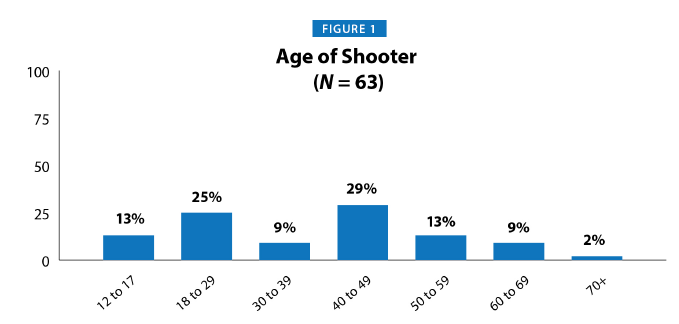

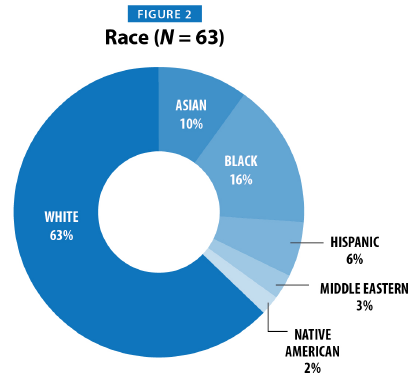

1. The 63 active shooters examined in this study did not appear to be uniform in any way such that they could be readily identified prior to attacking based on demographics alone.

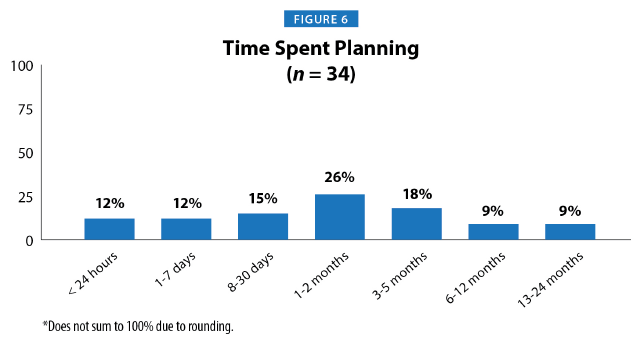

2. Active shooters take time to plan and prepare for the attack, with 77% of the subjects spending a week or longer planning their attack and 46% spending a week or longer actually preparing (procuring the means) for the attack.

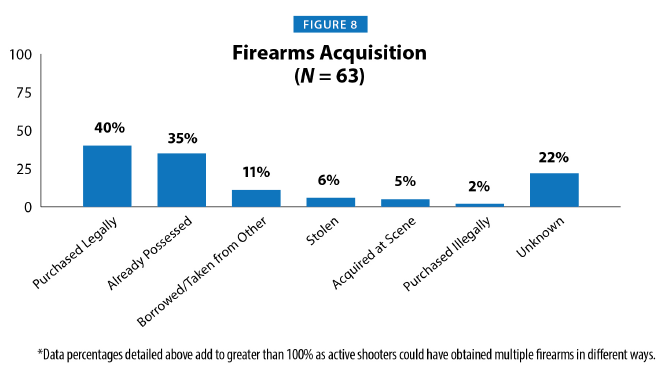

3. A majority of active shooters obtained their firearms legally, with only very small percentages obtaining a firearm illegally.

4. The FBI could only verify that 25% of active shooters in the study had ever been diagnosed with a mental illness. Of those diagnosed, only three had been diagnosed with a psychotic disorder.

5. Active shooters were typically experiencing multiple stressors (an average of 3.6 separate stressors) in the year before they attacked.

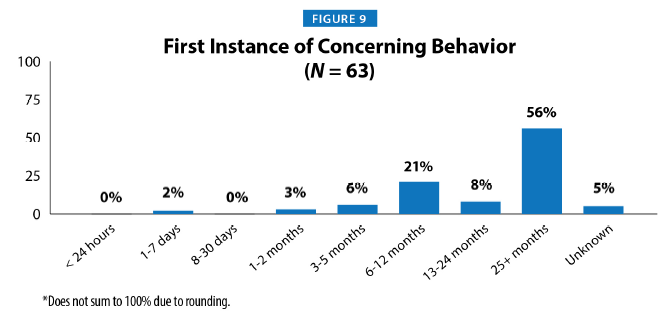

6. On average, each active shooter displayed 4 to 5 concerning behaviors over time that were observable to others around the shooter. The most frequently occurring concerning behaviors were related to the active shooter’s mental health, problematic interpersonal interactions, and leakage of violent intent.

7. For active shooters under age 18, school peers and teachers were more likely to observe concerning behaviors than family members. For active shooters 18 years old and over, spouses/domestic partners were the most likely to observe concerning behaviors.

8. When concerning behavior was observed by others, the most common response was to communicate directly to the active shooter (83%) or do nothing (54%). In 41% of the cases the concerning behavior was reported to law enforcement. Therefore, just because concerning behavior was recognized does not necessarily mean that it was reported to law enforcement.

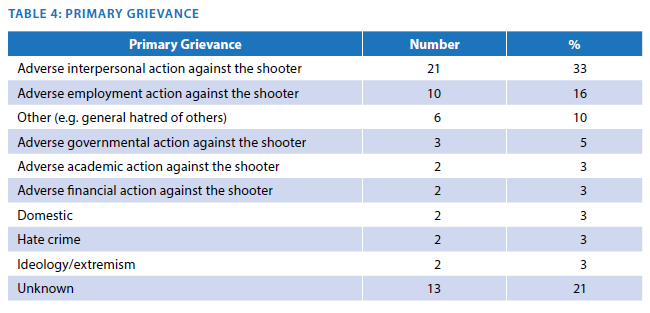

9. In those cases where the active shooter’s primary grievance could be identified, the most common grievances were related to an adverse interpersonal or employment action against the shooter (49%).

10. In the majority of cases (64%) at least one of the victims was specifically targeted by the active shooter.

…