FEDERAL RESERVE BANK GOVERNANCE: Opportunities Exist to Broaden Director Recruitment Efforts and Increase Transparency

- 127 pages

- October 2011

The Federal Reserve Act requires each Reserve Bank to be governed by a nine-member board—three Class A directors elected by member banks to represent their interests, three Class B directors elected by member banks to represent the public, and three Class C directors that are appointed by the Federal Reserve Board to represent the public. The diversity of Reserve Bank boards was limited from 2006 to 2010. For example, in 2006 minorities accounted for 13 of 108 director positions, and in 2010 they accounted for 15 of 108 director positions. Specifically, in 2010 Reserve Bank directors included 78 white men, 15 white women, 12 minority men, and 3 minority women. According to the Federal Reserve Act, Class B and C directors are to be elected with due but not exclusive consideration to the interests of agriculture, commerce, industry, services, labor, and consumer representation. During this period, labor and consumer groups had less representation than other industries. In 2010, 56 of the 91 directors that responded to GAO’s survey had financial markets experience. Reserve Banks generally review the current demographics of their boards and use a combination of personal networking and community outreach efforts to identify potential candidates for directors. Reserve Bank officials said that they generally limit their director search efforts to senior executives. GAO’s analysis of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission data found that diversity among senior executives is generally limited. While some Reserve Banks recruit more broadly, GAO recommends that the Federal Reserve Board encourage all Reserve Banks to consider ways to help enhance the economic and demographic diversity of perspectives on the boards, including by broadening their potential candidate pool.

The Federal Reserve System mitigates and manages the actual and potential conflicts of interest by, among other things, defining the directors’ roles and responsibilities, monitoring adherence to conflict-of-interest policies, and establishing internal controls to identify and manage potential conflicts. Reserve Bank directors are often affiliated with a variety of financial firms, nonprofits, and private and public companies. As the financial services industry evolves, more companies are becoming involved in financial services or interconnected with financial institutions. As a result, directors of all three classes can have ties to the financial sector. While these relationships may not give rise to actual conflicts of interest, they can create the appearance of a conflict as illustrated by the participation of director-affiliated institutions in the Federal Reserve System’s emergency programs. Moreover, some critics question the Reserve Bank boards’ involvement in supervision and regulation activities. GAO found that directors have a limited role in these activities, including voting on certain budget and personnel actions. Moreover, some Reserve Banks have further restricted the responsibilities of Class A directors, prohibiting their involvement in any personnel or budget decisions for this function. However, most Reserve Banks’ bylaws do not document the role of the board in supervision and regulation. To increase transparency, GAO recommends that all Reserve Banks clearly document the directors’ role in supervision and regulation activities in their bylaws. One option for addressing directors’ conflicts of interest is for the Reserve Bank to request a waiver from the Federal Reserve Board, which, according to officials, is rare. Most Reserve Banks do not have a process for formally requesting such waivers. To strengthen governance practices and increase transparency, GAO recommends that the Reserve Banks develop and document a process for requesting conflict waivers for directors. Further, GAO recommends that the Reserve Banks publicly disclose when a waiver is granted, as appropriate.

The Federal Reserve System’s governance practices are generally similar to those of selected central banks and comparable institutions such as bank holding companies and have similar selection procedures for directors. Further, most have similar accountability measures such as annual performance reviews. However, Reserve Bank governance practices tend to be less transparent than those of these institutions. For instance, comparable organizations make information on their board committees and ethics policies available on their websites; most Reserve banks do not. To further enhance transparency of Reserve Bank governance, GAO recommends that Reserve Banks make public key governance documents, such as bylaws, ethics policies, and committee assignments, by posting them to their websites.

…

Federal Reserve Bank directors often serve on the boards of a variety of financial firms as well as those of nonprofit, private, and public companies. For example, in 2010, 86 of 91 Reserve Bank directors responding to our survey held board positions at public and private companies, public and private universities, and nonprofit organizations. As noted earlier, our survey indicated that most of the Reserve Banks have directors who have held positions at financial services firms or insurance companies as well as banks. This includes Class A directors who are officials of banks that hold stock in the Reserve Bank, and Class C directors, who are required by the Federal Reserve Act to be persons of tested banking experience, which the Federal Reserve Board says has come to be interpreted as requiring familiarity with banking or financial services. In addition, as the financial services industry has evolved, more companies are involved in financial services or otherwise interconnected with financial institutions. These changes have resulted in a few Class B and Class C directors who were previously employed by financial institutions or have served on their boards.

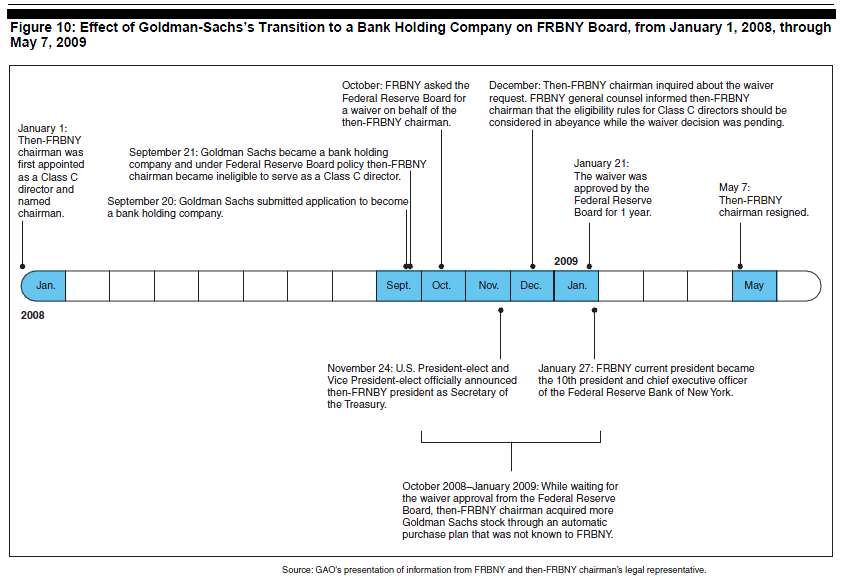

Directors’ Affiliations with Financial Firms

A recent example that raised questions about affiliations, and the nature of director affiliations with financial firms, involved the then-FRBNY chairman in late 2008, who was former chairman and a current board member and shareholder of the Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. (Goldman Sachs). As illustrated in figure 10, when the then-FRBNY chairman joined the FRBNY board as a Class C director in January 2008, Goldman Sachs was an investment bank outside the supervisory authority of the Federal Reserve System. However, in September 2008, in response to the unfolding financial crisis, Goldman Sachs applied for and was approved by the Federal Reserve Board to become a bank holding company. As a result, under Federal Reserve Board policy, the then-FRBNY chairman became ineligible to serve as a Class C director because he was then a director and stockholder of a bank holding company.

After completing their terms, directors who had represented member banks or who have affiliations with other financial institutions may maintain contact with Federal Reserve Bank officials for various reasons. FRBNY officials said that actions such as the Reserve Banks’ management of such communications may help safeguard against improprieties. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, the company of a former FRBNY director was negotiating with FRBNY regarding assets the Reserve Bank had acquired when it extended credit against the assets of Bear Stearns Companies, Inc. The former director felt that there was a miscommunication and contacted a number of FRBNY staff he knew to discuss the issue. The director’s preexisting relationship with FRBNY raised questions about the appropriateness of FRBNY’s actions in its negotiations with the former director’s firm. Recently, FRBNY implemented a procedure to document contacts involving directors by reporting calls and their content in a memo to the chairman of the board’s Audit and Operational Risk Committee.

…

Some of the institutions that borrowed from the emergency programs had senior executives and stockholders that served on Reserve Banks’ board of directors. These relationships contributed to questions about Reserve Bank governance and also raised concerns about conflicts of interest. We identified at least 18 former and current Class A, B, and C directors from 9 Reserve Banks who were affiliated with institutions that used at least one emergency program. In those cases, 11 Class A directors who served between 2008 and 2010 worked for member banks that used an emergency program. There are 2 Class B directors who served between 2008 and 2010 and worked for companies that used an emergency program. Similarly, one Class C director who served between 2008 and 2009 was affiliated with a company that used at least one program. In addition, there are 4 former Class A directors who served between 2006 and 2007 whose companies used the emergency facilities. The Term Auction Facility was the most commonly used facility.

According to Federal Reserve Board officials, the Federal Reserve Board allowed borrowers to access its emergency programs only if they satisfied publicly announced eligibility criteria. Thus, Reserve Banks granted access to borrowing institutions affiliated with Reserve Bank directors only if these institutions satisfied the proper criteria, regardless of potential director-affiliated outreach or whether the institution was affiliated with a director. As we reported in our July report, our analysis did not find evidence indicating a systemic bias toward favoring one or more eligible institutions.37 While some institutions that borrowed from these programs were affiliated with a Reserve Bank director, these institutions were subject to the same terms and conditions as those that had no such affiliation.

As another example, the Chief Executive Officer of JP Morgan Chase & Co. (JP Morgan Chase) served on the FRBNY board of directors at the same time that his bank participated in various emergency programs and served as one of the clearing banks for emergency lending programs. According to Federal Reserve Board officials, there are only two entities, including JP Morgan Chase, that offer services as clearing banks for triparty repurchase agreements and both banks served as clearing banks for the emergency programs. Similarly, Lehman’s Chief Executive Officer served on the FRBNY board while Lehman’s broker-dealer subsidiary participated in emergency programs such as the Primary Dealer Credit Facility.