Cultural Intelligence for Military Operations

- 20 pages

- For Official Use Only

- May 2003

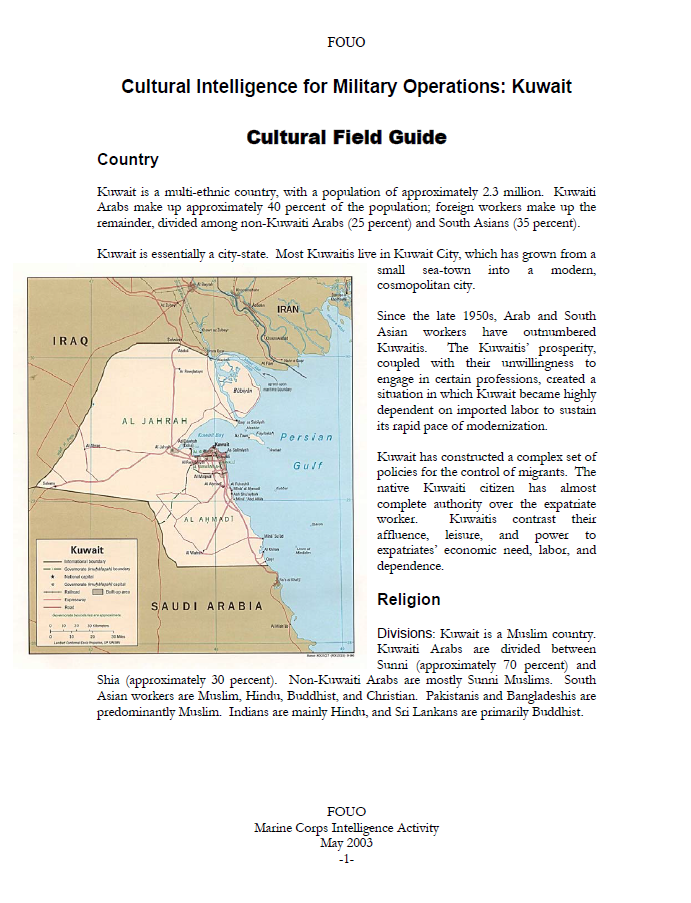

Kuwait is a multi-ethnic country, with a population of approximately 2.3 million. Kuwaiti Arabs make up approximately 40 percent of the population; foreign workers make up the remainder, divided among non-Kuwaiti Arabs (25 percent) and South Asians (35 percent). Kuwait is essentially a city-state. Most Kuwaitis live in Kuwait City, which has grown from a small sea-town into a modern, cosmopolitan city.

Since the late 1950s, Arab and South Asian workers have outnumbered Kuwaitis. The Kuwaitis’ prosperity, coupled with their unwillingness to engage in certain professions, created a situation in which Kuwait became highly dependent on imported labor to sustain its rapid pace of modernization. Kuwait has constructed a complex set of policies for the control of migrants. The native Kuwaiti citizen has almost complete authority over the expatriate worker. Kuwaitis contrast their affluence, leisure, and power to expatriates’ economic need, labor, and dependence.

Religion

Divisions: Kuwait is a Muslim country. Kuwaiti Arabs are divided between Sunni (approximately 70 percent) and Shia (approximately 30 percent). Non-Kuwaiti Arabs are mostly Sunni Muslims. South Asian workers are Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, and Christian. Pakistanis and Bangladeshis are predominantly Muslim. Indians are mainly Hindu, and Sri Lankans are primarily Buddhist.

Islam is more of a unifying than an excluding factor in Kuwait, and the Sunni-Shia division has caused fewer problems there than in neighboring states. As a mark of identity, religious affiliation is less significant than citizenship and ethnic origin. However, there is a close association between Islamic values and Kuwaiti cultural identity.

Adherents of religions other than Islam practice their religion quietly, observing festivals and practicing rituals in private. These communities recognize that conspicuous displays of religion—in the form of temples or marriage processions—can be provocative in Kuwait.

Geographic Differences: There are no major geographic differences with respect to religion because most of Kuwait’s population lives in and around Kuwait City. However, foreign workers—whether Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, or Christian—are largely segregated from Kuwaitis in residential neighborhoods.

…

Customs

Greeting: Arabs often greet each other with a number of ritual phrases and fixed responses. Elaborate greetings and inquiries about health and well-being often take up large amounts of time, but are necessary in establishing friendly relations. These elaborate greetings originate from Bedouin tradition where the nomadic lifestyle led to frequent encounters with strangers. Arabs will often shake hands every time they meet and every time they depart. Arabs will rise when shaking hands as well as when an esteemed person enters a room. Handshakes are generally long in length and may involve grasping the elbow. They usually do not possess the same firmness as those of Americans.

Namaskar or Namaste is the most popular form of greeting among Indians. Both palms are placed together and raised below the face. It is a general salutation that is used to both welcome somebody and to bid farewell. Other forms of greeting common among India’s various communities include the Sikh Sat-Sri-akal and the Tamilian Vannakkam.

Handshakes are the common form of greeting between two Pakistani males. Close friends and relatives may embrace. Women may greet each other with a kiss or an embrace.

Ayubowan, which means “May you live long,” is the customary Sri Lankan greeting. Palms held close together against the chest denotes welcome, goodbye, respect, devotion, or loyalty. Gifts should be given or received with both hands.

When greeting non-Muslims, Bangladeshis use the Indian Namaskar greeting. When greeting fellow Muslims, they use Asalaam walaikhum, which means “peace be upon you.” Gestures/Hand Signs: Arabs, like most people, use gestures and body movements to communicate. It has been said that “To tie an Arab’s hands while he is speaking is tantamount to tying his tongue.” However, Arab gestures differ a great deal from American ones.

Arabs may make the following gestures/hand signs: Placing the right hand or its forefinger on the tip of the nose, on the right lower eyelid, on top of the head, or on the mustache or beard means “it’s in front of me,” “I see it,” or “it’s my obligation.” Placing the palm of the right hand on the chest immediately after shaking hands with another man shows respect or thanks. Touching the tips of the right fingertips to the forehead while bowing the head slightly also connotes respect. Holding the fingers in a pear shaped configuration with the tips pointing up at about waist level and moving the hand slightly up and down signals “be patient” or “be careful.” Flicking the right thumbnail on front teeth can mean “I have no money.”

Visiting: Arabs are, in general, hospitable and generous. Their hospitality is often expressed with food. Giving a warm reception to strangers stems from the culture of the desert, where traveling nomads depended on the graciousness and generosity of others to survive. Arabs continue this custom of showing courtesy and consideration to strangers. Demonstrating friendliness, generosity and hospitality are considered expressions of personal honor. When Arabs are visiting an installation or office, they will expect the same level of generosity and attention.

Indians offer flower garlands to visitors as a mark of respect and honor. Visiting is an important part of Pakistani culture, and hospitality is the mark of good family. Guests are offered refreshments and perhaps invited to share a meal. However, because most Pakistani workers in Kuwait share small apartments, it is difficult for them to follow this custom.

Negotiations: Arab culture places a premium on politeness and socially correct behavior. Preserving honor is paramount. When faced with criticism, Arabs will try to protect their status and avoid incurring negative judgments by others. This concept can manifest itself in creative descriptions of facts or in the dismissal of conclusions, in order to protect one’s reputation. This cultural trait will generally take precedence over the accurate transmission of information.

The desire to avoid shame and maintain respect can also contribute to the tendency to compartmentalize information. One common manifestation of this behavior comes in the form of saying “yes” when one really means “no.” Arabs try to take the personalization out of contentious conversations, which can lead to vagueness and efforts to not speak in absolutes. It is also considered disrespectful to contradict or disagree with a person of superior rank or age.

Conflict Resolution: In Arab society, community affiliation is given priority over individual rights. Consequently, familial and status considerations factor significantly into the processes and outcomes of conflict resolution. This emphasis on community helps explain the dominance of informal over contractual commitments and the use of mediation to solve conflicts. Many disputes are resolved informally outside of the official courts.

Business Style: In business meetings formal courtesies are expected. Cards—which should be printed in both English and Arabic—are regularly exchanged. Meetings may not always be on a one-to-one basis and it is often difficult to confine conversation to the business at hand. Many topics may be discussed in order to assess the character of potential business partners. There is a strong preference within Arab culture for business transactions to be based on personal contacts.

Sense of Time and Space: Past and present are flexible concepts in Arab society, with one shading over into the other. In general, time is much less rigidly scheduled than in Western culture. However, it is considered rude to be late to an appointment as is looking at one’s watch or acting pressed for time. Additionally, Arabs believe that future plans may interfere with the will of God. Commitments a week or more into the future are less common than in Western culture.

Olfaction functions as a distance-setting mechanism. Standing close enough to smell someone’s breath and body odor is a sign that one wants to relate and interact with them. To stand back and away from someone indicates a desire not to interact with them and may offend the individual. Additionally, Arabs feel very comfortable when surrounded by people in open spaces, but can feel uncomfortable or threatened when enclosed within walls in small physical spaces.

Arabs also have a non-Western view of property and boundaries. Traditionally Arabs do not subscribe to the concept of trespassing. Arabs have conformed to the Western imposition of country boundaries, but do not place the same boundary restrictions within their country as it relates to city, town, village, property, and yard.

Hygiene: Personal hygiene is extremely important to Arabs for both spiritual and practical reasons. Because meals are frequently eaten by hand, it is typical to wash the hands before and after eating. Formal washing of the face, hands, and forearms, called wudhu, and general cleanliness of the body and clothing is required before daily prayers or fasting. A formal head-to-toe washing, called ghusi, is required after sexual intercourse, ejaculation (for men), and menstruation (for women). Ghusi is also recommended following contact with other substances considered unclean, including alcohol, pigs, dogs, or non-believers.

Gifts: Small gifts and candies are considered appropriate gifts for those invited to Arab homes. It is customary that gifts are not opened in front of people. Unlike Westerners, Arabs do not feel it necessary to bring gifts when visiting someone’s home. It is the responsibility of the host to provide for a guest in Arab culture.

Cultural Do’s and Don’ts: It is insulting to ask about a Muslim’s wife or another female family member. Don’t stare at women on the street or initiate conversation with them. If meeting a female, do not attempt to shake her hand unless she extends it. In addition, never greet a woman with an embrace or kiss. Avoid pointing a finger at an Arab or beckoning with a finger. Use the right hand to eat, touch, and present gifts; the left is generally regarded as unclean. Avoid putting feet on tables or furniture. Refrain from leaning against walls, slouching in chairs, and keeping hands in pockets. Do not show the soles of the feet, as they are the lowest and dirtiest part of the body.