The report describes characteristics of 209 Americans who committed espionage-related offenses against the U.S. since 1947. Three cohorts are compared based on when the individual began espionage: 1947-1979, 1980-1989, and 1990-2015. Using data coded from open published sources, analyses are reported on personal attributes of persons across the three cohorts, the employment and levels of clearance, how they committed espionage, the consequences they suffered, and their motivations. The second part of the report explores each of the five types of espionage committed by the 209 persons under study. These include: classic espionage, leaks, acting as an agent of a foreign government, violations of export control laws, and economic espionage. The statutes governing each type are discussed and compared. Classification of national security information is discussed as one element in espionage. In Part 3, revisions to the espionage statutes are recommended in light of findings presented in the report.

…

This report is the fourth in the series on espionage by Americans that the Defense Personnel and Security Research Center (PERSEREC) began publishing in 1992. The current report updates earlier work by including recent cases, and it extends the scope by exploring related types of espionage in addition to the classic type. There are three parts to this report. Part 1 presents characteristics of Americans who committed espionage-related offenses since 1947 based on analyses of data collected from open sources. Part 2 explores the five types of espionage committed by the 209 individuals in this study: classic espionage, leaks, acting as an agent of a foreign government, violations of export control laws, and economic espionage. Each type is described by its legal bases, and examples of cases and comparisons with the other types of espionage are provided. Part 3 considers the impact of the changing context in which espionage takes place, and discusses two important developments: information and communications technologies (ICT) and globalization. Recommendations are offered for revisions to the espionage statutes in response to these accelerating changes in context.

Part 1 compares data across three cohorts of persons based on when the individual began espionage: 1947-1979 (the early Cold War), 1980-1989 (the later Cold War), and 1990-2015 (the post-Soviet period). As the Cold War recedes in time, the recent cohort offers the most applicable data for the present. Among the characteristics of the 67 Americans who committed espionage-related offenses since 1990:

•They have usually been male and middle-aged. Half were married.

•Reflecting changes in the population as a whole, they were more diverse inracial and ethnic composition, and more highly educated than earlier cohorts.

•Three-quarters have been civil servants, one-quarter military, and compared tothe previous two cohorts, increasing proportions have been contractors, heldjobs not related to espionage, and/or not held security clearances.

•Three-quarters succeeded in passing information, while one-quarter wereintercepted before they could pass anything.

•Sixty percent were volunteers and 40% were recruited. Among recruits, 60%were recruited by a foreign intelligence service and 40% by family or friends.Contacting a foreign embassy was the most common way to begin as avolunteer.

•Compared to earlier cohorts in which the Soviet Union and Russiapredominated as the recipient of American espionage, recent espionageoffenders have transmitted information to a greater variety of recipients.

•Shorter prison sentences have been the norm in the recent past.

•Sixty-eight percent of people received no payment.

•Money is the most common motive for committing espionage-related offenses,but it is less dominant than in the past. In the recent cohort, money was amotive for 28%, down from 41% and 45% in the first and second cohorts,respectively. Divided loyalties is the second most common motive (22%).Disgruntlement and ingratiation are nearly tied for third place, and more peopleseek recognition as a motive for espionage.

Returning to the full population, the majority of the 209 individuals committed classic espionage in which controlled national security information, usually classified, was transmitted to a foreign government. Classic espionage predominates in each cohort, but declined from 94% the first cohort to 78% in the most recent. This reflects authorities’ recent increasing treatment as espionage of the four additional types discussed in Part 2: leaks; acting as an agent of a foreign government; violations of export control laws; and economic espionage. Each of the four additional types is prosecuted under its own subset of statutes, which differs from those used in cases of classic espionage. The various types are usually handled by different federal agencies. They also differ in how involved the information of private companies and corporations is alongside government agencies.

The five types of espionage are not mutually exclusive, and a person may be charged with and convicted of more than one type. The assumption that espionage consists simply of classic espionage should be reexamined in light of how these four additional crimes are similar to or even charged as identical to classic espionage. All five types impose losses of national defense information, intellectual property, and/or advanced technologies that cause grave damage to the security and economy of the nation.

Four elements frame the analyses in Part 2. First, the legal statutes that define the crimes are identified and described. Prosecutorial choices as to which statutes to use are considered, alternate statutes that have been used in similar circumstances are identified, and reasons for the choices suggested. Second, examples of each type of espionage are presented as case studies. Third, issues resulting from classification of information are identified and discussed for each type, if applicable. Fourth, the numbers of individuals among the 209 are presented in tables for each of the five types, along with descriptive statistics to identify trends over time.

Part 3 discusses these trends by recognizing two central dimensions of the current context in which espionage occurs: ICT and globalization. Spies have moved with the times, and they employ all the technological sophistication and advantages they can access. Implications from this changing context are discussed, including how American espionage offenders gather, store, and transmit intelligence to a foreign government, and how a foreign government may now steal controlled information directly across interconnected networks, threatening to make spies obsolete.

Globalization affects many dimensions of life, and is especially apparent in areas relevant to espionage, such as political and military affairs, development of defense technologies, and international finance. It can influence the recruitment of spies and the likelihood that people will volunteer to commit espionage as a consequence of the ongoing trend toward a global culture, with its easy international transmission of ideas, civic ideals, and loosening allegiances of citizenship.

This report concludes by recommending revisions to the espionage statutes (Title 18 U.S.C. § 792 through 798) in order to address inconsistencies and ambiguities. Based on provisions enacted in 1917 and updated in last 1950, they are outdated. Three approaches to revision are outlined. First, try to eliminate inconsistencies among the espionage statutes themselves. Second, consider how to update the espionage statutes to reflect the current context of cyber capabilities, the Internet, and globalization. Third, consider how to amend the statutes that apply to all five types of espionage discussed in this report to reconcile inequities, eliminate gaps or overlaps, and create more consistency in the legal response to activities that are similar, even though they take place in different spheres.

In an appendix, this report examines how espionage fits into the broader study of insider threat, and considers three insights from insider threat studies that may illuminate espionage: personal crises and triggers, indicators of insider threat, and the role of organizational culture.

…

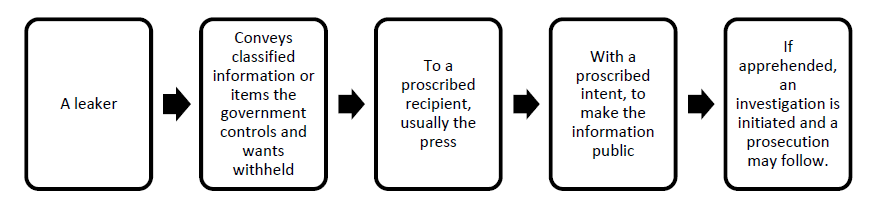

LEAKS AS A TYPE OF ESPIONAGE

Leaks are disclosures of classified information to the public. They are usually accomplished through the press or by publication in print or electronic media. A leak follows the form of classic espionage except that the recipient is different. Instead of being given to an agent of a foreign power or transnational adversary, leaks go out to the American public. Then, through modern communication channels, the information is transmitted around the world as it is re-published, translated, and discussed in additional press coverage. Both the content of the information and the fact that it is no longer under the government’s control are made available to everyone, including adversaries who systematically monitor the American press for insights.

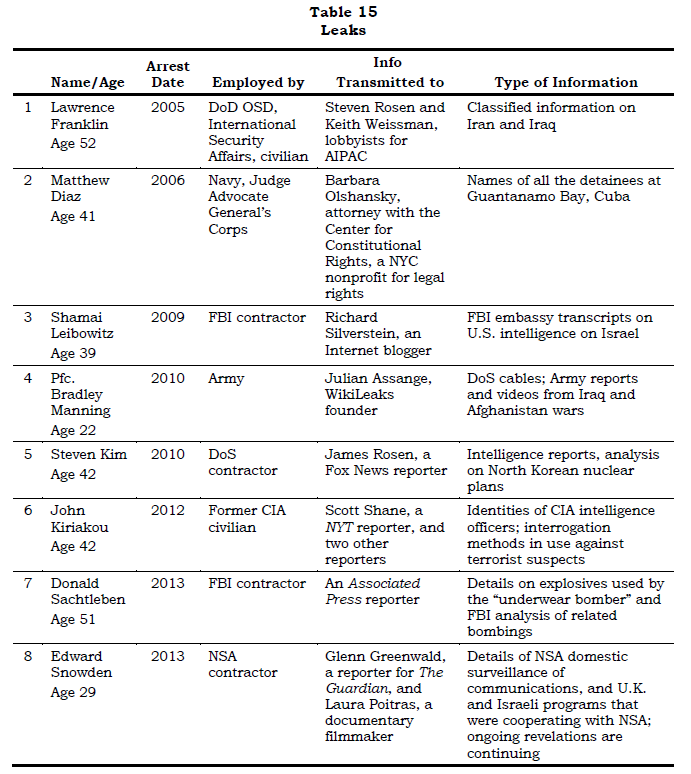

The seven leakers discussed here were diverse. They ranged in age from 22 to 52 years of age: one person was 22, four persons were in their middle years (their 30s or 40s), and two persons were in their early 50s. They worked in various agencies: two were members of the military (U.S. Navy and U.S. Army); two were civilian federal employees, current or former (OSD and CIA); and three were contractors (two to the FBI, and one to DoS). They had reached different stages in their careers, from an Army Private First Class to people at mid-career to a respected senior defense policy specialist. Three common motives run through the seven cases.

•The leakers strongly objected to something they saw being done in the course oftheir work. Franklin, Diaz, Leibowitz, Kiriakou, and Manning each objected to government policies or actions that they observed, and they chose to intervene,usually by making their objections public by releasing classified information.

•The leakers enjoyed playing the role of expert. Franklin, Leibowitz, Kim, Kiriakou, and Sachtleben each sought out or responded to opportunities to share their expertise.

•The leakers wanted to help and saw themselves as helping. Diaz, Kim, and Manning, were, in their view, trying to help people they had befriended or with whom they sympathized.

To illustrate how leaks are a form of espionage in most ways, but not in every way, the elements of classic espionage discussed earlier are here applied to the actions of Franklin based on details are from his superseding indictment (United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, 2005).

•A context of competition. Franklin’s job was to monitor the hostile international relationship between the U.S. and Iran after its 1979 revolution. After 9/11, a debate simmered in Franklin’s agency over preparations for the invasion of Iraq.

•Secret means. Franklin verbally conveyed highly classified information to recipients in meetings held in places where they were less likely to be observed.

•Goal is secrets. Rosen and Weissman sought out a well-placed contact in OSD who could provide them with information. Rosen is quoted as saying on the telephone “that he was excited to meet with a ‘Pentagon guy’ [Franklin] because this person was a ‘real insider.’”

•Political, military, economic secrets. The classified information Franklin leaked to Rosen and Weissman included CIA internal reports on Middle Eastern countries, internal deliberations by federal officials, policy documents, and national intelligence concerning Al Qaeda and Iraq.

•Theft. Franklin was not accused of passing stolen documents to the recipients,only verbal information based on them. He was accused of stealing and taking home classified documents.

•Subterfuge and surveillance. Franklin, Rosen, and Weissman held their meetings at various restaurants, coffee shops, sports facilities, baseball games,and landmarks in the Washington, DC, area. In one instance, they met at Union Station, and conducted their conversations at three different restaurants.

•Illegality. Franklin was convicted of Title 18 U.S.C. § 793(d) and (e).

•Psychological toll. In July 2004, after the FBI explained the evidence and the likely consequences of a prison term on his family, Franklin took the FBI’s bargain for leniency and wore a wire during subsequent conversations with Rosen and Weissman.