Public Intelligence

Despite the U.S. military’s massive spending each year on advanced communications technology, the use of simple text chat or tactical chat has outpaced other systems to become one of the most popular paths for communicating practical information on the battlefield. Though the use of text chat by the U.S. military first began in the early 1990s, in recent years tactical chat has evolved into a “primary ‘comms’ path, having supplanted voice communications as the primary means of common operational picture (COP) updating in support of situational awareness.” An article from January 2012 in the Air Land Sea Bulletin describes the value of tactical chat as an effective and immediate communications method that is highly effective in distributed, intermittent, low bandwidth environments which is particularly important with “large numbers of distributed warfighters” who must “frequently jump onto and off of a network” and coordinate with other coalition partners. Text chat also provides “persistency in situational understanding between those leaving and those assuming command watch duties” enabling a persistent record of tactical decision making.

A 2006 thesis from the Naval Postgraduate School states that internet relay chat (IRC) is one of the most widely used chat protocols for military command and control (C2). Software such as mIRC, a Windows-based chat client, or integrated systems in C2 equipment are used primarily in tactical conditions though efforts are underway to upgrade systems to newer protocols. “Transition plans (among and between the Services) for migrating thousands of users to modern protocols and cloud-computing integration has been late arriving” according to the Air Land Sea Bulletin. Both the Navy and the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) are working towards utilizing the extensible messaging and presence protocol (XMPP) in future applications.

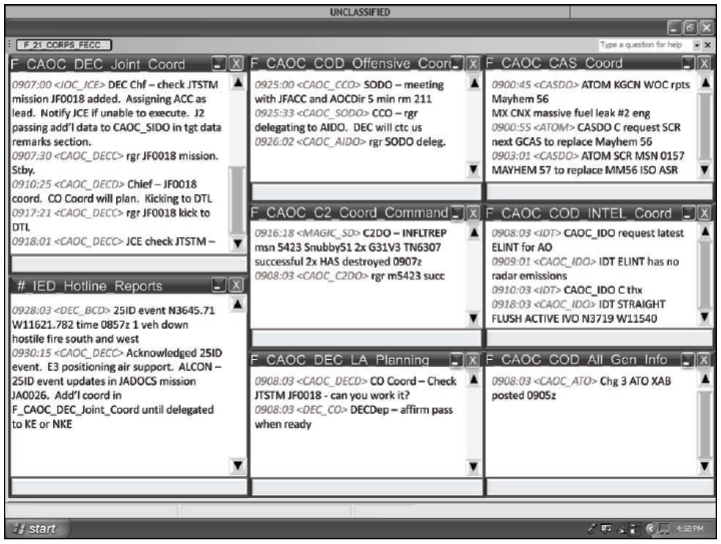

In 2009, the Air Land Sea Applications Center issued a multi-service tactics, techniques, and procedures (MTTP) manual attempting to codify the protocols and standards for the usage of tactical chat throughout the services. The manual provides a common language for tactical chat, unifying disparate usage standards in different services such as “consistent naming conventions for rooms, people, and battle roles and activities” and “archival agreements among multiple user communities”. For example, the manual provides naming conventions for chat room users, demonstrating how to construct user names that clearly indicate the user’s role and unit. A 4th Infantry Division Plans Officer should utilize the call sign 4ID_OPS_PLANS when engaging in tactical chat while a Tactical Action Officer aboard the USS Enterprise should use the name CVN65_ENT_TAO. The manual also provides standards for naming chat rooms and managing large numbers of rooms simultaneously for coordinating missions and situational awareness. A helpful glossary also provides translations of tactical chat abbreviations and terms, such as canx meaning cancel and rgr for roger.

The MTTP manual describes how tactical chat can be used for a variety of purposes to support “coordination, integration, and execution of missions” including everything from maneuver and logistics to intelligence, fires and force protection. One vignette presented in the manual describes how tactical chat or TC might be used in a cordon and search operation:

“During a day mission by ground maneuver units conducting cordon and search operations in a small village known for harboring insurgents, a Predator UAS flying in support of troops on the ground spotted movement on the roof of a previously searched building. The UAS operator, noticing that the forces conducting the cordon and search had already begun moving away from the structure, used TC to immediately notify the ground unit’s [tactical operations center] that an individual was moving on the roof and appeared to be getting into a hide site. After communicating this information to the troops on the ground, the TOC confirmed that the individual seen by the UAS was not in their unit, and with the assistance of the UAS operator using TC, was able to direct his troops to reenter the building and ‘talk’ them to the suspected hide site over voice communications. The individual hiding on the rooftop was then captured. The use of TC in this instance was critical to the capture of an insurgent that would otherwise have escaped.”

Tactical chat can also be used for targeting the enemy and receiving clearance to fire, enhancing “the collective and coordinated use of indirect and joint fires through the targeting process.” Rather than contacting “several agencies via radio or telephone and taking several minutes to initiate fire missions on a fleeing target or in the middle of a TIC [troops in contact]”, unit fire support elements can use tactical chat to request clearance and deconflict airspace required for the mission in a matter of seconds, which is helpful in locations like Afghanistan where ground units are commonly separated by more than 90 kilometers. According to the manual, the chat room transaction in such a situation might appear like this:

[03:31:27] <2/1BDE_BAE_FSE> IMMEDIATE Fire Mission, POO, Grid 28M MC 13245 24512, Killbox 32AY1SE, POI GRID 28M MC 14212 26114, Killbox 32AY3NE, MAX ORD 8.5K

[03:31:28] <CRC_Resolute> 2/1BDE_BAE_FSE, stby wkng

[03:31:57] <CRC_Resolute> 2/1BDE_BAE_FSE, Resolute all clear

[03:32:04] <2/1BDE_BAE_FSE> c

[03:41:23] <2/1BDE_BAE_FSE> EOM

[03:41:31] <CRC_Resolute> c

A fire mission request is sent to the control and reporting center (CRC) controller who then works to deconflict the airspace and report back that the space is now clear. Once the mission is complete, the brigade fire support element notifies users with the statement EOM or end of mission.

In this case, the brevity of tactical chat allows for fast and simple communication, enabling the brigade fire support element to receive a reply in seconds and continue with their mission. However, it is this very aspect of tactical chat, its speed and brevity, that can sometimes create confusion on the battlefield. Similar to the public world of social media, tactical chat allows inaccurate or misleading information to be widely disseminated and sent to all users just “as quickly as accurate information.” According to the MTTP manual, tactical chat’s “short text messages can cause ambiguity and accuracy can be compromised without strict adherence to standard terminology”, allowing users to quickly proliferate inaccurate or misleading information that can affect operations. A 2003 article from U.S. News and World Report describes some of the problems created by the use of tactical chat in Operation Iraqi Freedom. In one example, a pilot’s widely reported sighting of vehicles moving towards the Kuwaiti border turned out to be a “large band of hungry camels.” In another example, a radio intercept was disseminated that reportedly discussed Iraqi soldiers using poisonous artillery rounds. The copy-and-paste nature of tactical chat led to news of the intercept proliferating fast throughout military chat networks with many saying that the Iraqis were “loading chemical rounds”. The buzz continued until an Arabic linguist clarified that the intercept was mistranslated and that the rounds were not poisonous, they had just gone bad.