CRS Report

- 52 pages

- September 3, 2010

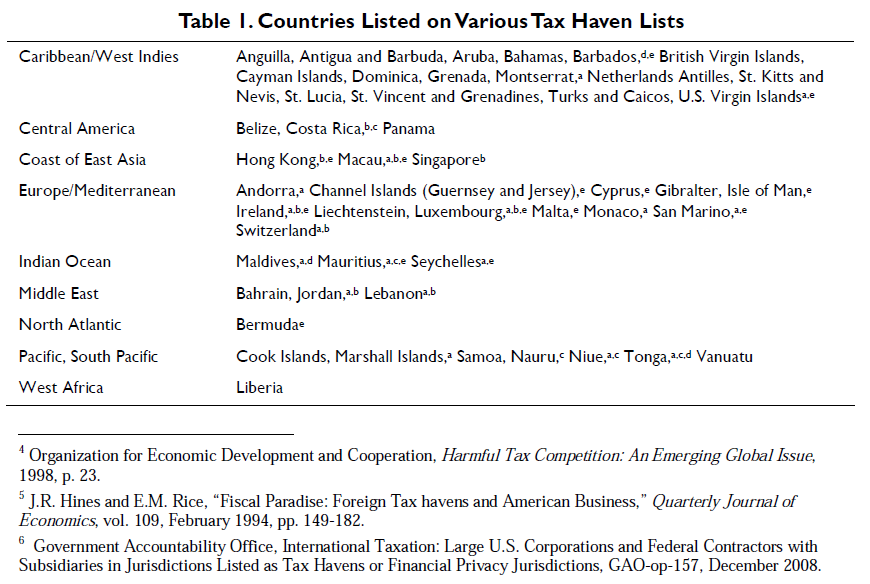

The federal government loses both individual and corporate income tax revenue from the shifting of profits and income into low-tax countries, often referred to as tax havens. The revenue losses from this tax avoidance and evasion are difficult to estimate, but some have suggested that the annual cost of offshore tax abuses may be around $100 billion per year. International tax avoidance can arise from large multinational corporations who shift profits into low-tax foreign subsidiaries or wealthy individual investors who set up secret bank accounts in tax haven countries.

Recent actions by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the

G-20 industrialized nations have targeted tax haven countries, focusing primarily on evasion

issues. The recently adopted HIRE Act (P.L. 111-147) included a number of anti-evasion

provisions, and P.L. 111-226 included foreign tax credit provisions. Some of these proposals, and

some not adopted, are in the American Jobs and Closing Loopholes Act (H.R. 4213); the Stop Tax

Haven Abuse Act (S. 506, H.R. 1265); draft proposals by the Senate Finance Committee; two

other related bills, S. 386 and S. 569; the Bipartisan Tax Fairness and Simplification Act (S.

3018); and proposals by President Obama.Multinational firms can artificially shift profits from high-tax to low-tax jurisdictions using a

variety of techniques, such as shifting debt to high-tax jurisdictions. Since tax on the income of

foreign subsidiaries (except for certain passive income) is deferred until repatriated, this income

can avoid current U.S. taxes and perhaps do so indefinitely. The taxation of passive income

(called Subpart F income) has been reduced, perhaps significantly, through the use of “hybrid

entities” that are treated differently in different jurisdictions. The use of hybrid entities was

greatly expanded by a new regulation (termed “check-the-box”) introduced in the late 1990s that

had unintended consequences for foreign firms. In addition, earnings from income that is taxed

can often be shielded by foreign tax credits on other income. On average very little tax is paid on

the foreign source income of U.S. firms. Ample evidence of a significant amount of profit shifting

exists, but the revenue cost estimates vary from about $10 billion to $60 billion per year.

Individuals can evade taxes on passive income, such as interest, dividends, and capital gains, by

not reporting income earned abroad. In addition, since interest paid to foreign recipients is not

taxed, individuals can also evade taxes on U.S. source income by setting up shell corporations

and trusts in foreign haven countries to channel funds. There is no general third party reporting of

income as is the case for ordinary passive income earned domestically; the IRS relies on qualified

intermediaries (QIs) who certify nationality without revealing the beneficial owners. Estimates of

the cost of individual evasion have ranged from $40 billion to $70 billion.Most provisions to address profit shifting by multinational firms would involve changing the tax

law: repealing or limiting deferral, limiting the ability of the foreign tax credit to offset income,

addressing check-the-box, or even formula apportionment. President Obama’s proposals include a

proposal to disallow overall deductions and foreign tax credits for deferred income and

restrictions on the use of hybrid entities. Provisions to address individual evasion include

increased information reporting and provisions to increase enforcement, such as shifting the

burden of proof to the taxpayer, increased penalties, and increased resources. Individual tax

evasion is the main target of the HIRE Act, the proposed Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act, and the

Senate Finance Committee proposals; some revisions are also included in President Obama’s

plan.…