CRS Report

- Amy F. Wolf, Specialist in Nuclear Weapons Policy

- 30 pages

- February 23, 2009

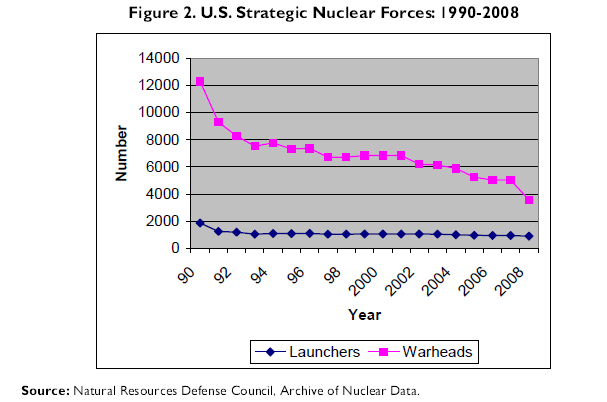

During the Cold War, the U.S. nuclear arsenal contained many types of delivery vehicles for nuclear weapons. The longer range systems, which included long-range missiles based on U.S. territory, long-range missiles based on submarines, and heavy bombers that could threaten Soviet targets from their bases in the United States, are known as strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. At the end of the Cold War, in 1991, the United States deployed more than 10,000 warheads on these delivery vehicles. That number has declined to less than 6,000 warheads today, and is slated, under the 2002 Moscow Treaty, to decline to 2,200 warheads by the year 2012. At the present time, the U.S. land-based ballistic missile force (ICBMs) consists of 450 Minuteman III ICBMs, each deployed with between one and three warheads, for a total of 1,200 warheads. The Air Force recently deactivated all 50 of the 10-warhead Peacekeeper ICBMs; it plans to eventually deploy Peacekeeper warheads on some of the Minuteman ICBMs. It has also deactivated 50 Minuteman III missiles. The Air Force is also modernizing the Minuteman missiles, replacing and upgrading their rocket motors, guidance systems, and other components. The Air Force had expected to begin replacing the Minuteman missiles around 2018, but has decided, instead, to continue to modernize and maintain the existing missiles. The U.S. ballistic missile submarine fleet currently consists of 14 Trident submarines; each carries 24 Trident II (D-5) missiles. The Navy has converted 4 of the original 18 Trident submarines to carry non-nuclear cruise missiles. The remaining submarines currently carry around 2,000 warheads in total, a number that will likely decline as the United States implements the Moscow Treaty. The Navy has shifted the basing of the submarines, so that nine are deployed in the Pacific Ocean and five are in the Atlantic, to better cover targets in and around Asia. It also has undertaken efforts to extend the life of the missiles and warheads so that they and the submarines can remain in the fleet past 2020.

The U.S. fleet of heavy bombers currently includes 20 B-2 bombers and 94 B-52 bombers. The B-1 bomber no longer is equipped for nuclear missions. The 2006 QDR recommended that the Air Force reduce the B-52 fleet to 56 aircraft; Congress rejected that recommendation, but will allow the fleet to decline to 76 aircraft. The Air Force has also begun to retire the nuclear-armed cruise missiles carried by B-52 bombers, leaving only about half the B-52 fleet equipped to carry nuclear weapons.

Congress has reviewed the Bush Administration’s plans for U.S. strategic nuclear forces during the annual authorization and appropriations process. It has reviewed a number of questions about the future size of that force. For example, some have questioned why the United States must retain 2,200 strategic nuclear warheads. Congress may also question the Administration’s plans for reductions in the Minuteman force and B-52 fleet. This report will be updated as needed.

…

…

Since the early 1960s the United States has maintained a “triad” of strategic nuclear delivery vehicles, The United States first developed these three types of nuclear delivery vehicles, in large part, because each of the military services wanted to play a role in the U.S. nuclear arsenal. However, during the 1960s and 1970s, analysts developed a more reasoned rationale for the nuclear “triad.” They argued that these different basing modes had complementary strengths and weaknesses. They would enhance deterrence and discourage a Soviet first strike because they complicated Soviet attack planning and ensured the survivability of a significant portion of the U.S. force in the event of a Soviet first strike.9 The different characteristics might also strengthenthe credibility of U.S. targeting strategy. For example, ICBMs eventually had the accuracy and prompt responsiveness needed to attack hardened targets such as Soviet command posts and ICBM silos, SLBMs had the survivability needed to complicate Soviet efforts to launch a disarming first strike and to retaliate if such an attack were attempted,10 and heavy bombers could be dispersed quickly and launched to enhance their survivability, and they could be recalled to their bases if a crisis did not escalate into conflict.

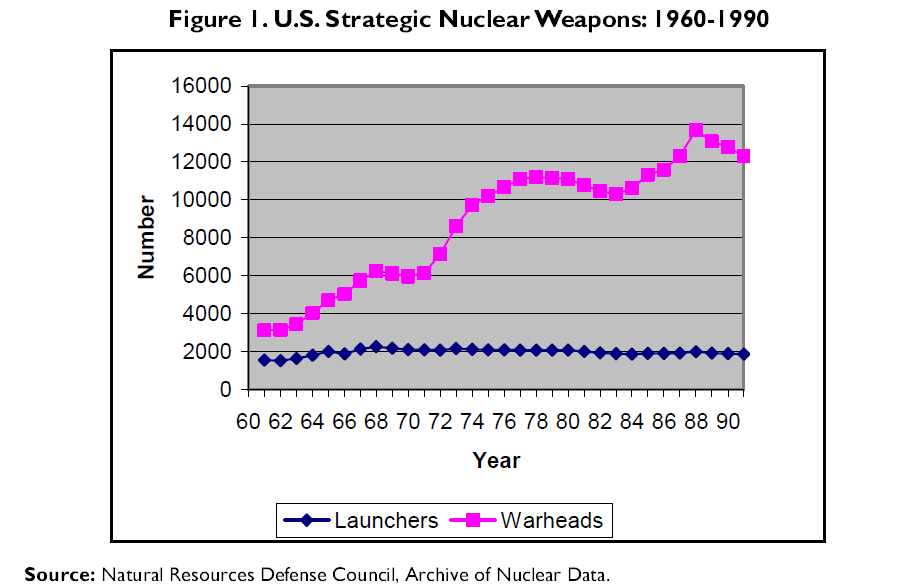

According to unclassified estimates, the number of delivery vehicles (ICBMs, SLBMs, and nuclear-capable bombers) in the U.S. force structure grew steadily through the mid-1960s, with the greatest number of delivery vehicles, 2,268, deployed in 1967.11 The number then held relatively steady through 1990, at between 1,875 and 2,200 ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers. The number of warheads carried on these delivery vehicles increased sharply through 1975, then, after a brief pause, again rose sharply in the early 1980s, peaking at around 13,600 warheads in 1987. Figure 1 displays the increases in delivery vehicles and warheads between 1960, when the United States first began to deploy ICBMs, and 1990, the year before the United States and Soviet Union signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START).

…

Future Force Structure and Size

The Bush Administration stated in late 2001 that the United States would reduce its strategic nuclear forces to 1,700-2,200 “operationally deployed warheads” over the next decade. This goal was codified in the 2002 Moscow Treaty. According to the Administration, operationally deployed warheads are those deployed on missiles and stored near bombers on a day-to-day basis. They are the warheads that would be available immediately, or in a matter of days, to meet “immediate and unexpected contingencies.” The Administration also indicated that the United States would retain a triad of ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers for the foreseeable future. It did not, however, offer a rationale for this traditional “triad,” although the points raised in the past

about the differing and complementary capabilities of the systems probably still pertain. Admiral James Ellis, the former Commander of the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) highlighted this when he noted in a 2005 interview, that the ICBM force provides responsiveness, the SLBM force provides survivability, and bombers provide flexibility and recall capability. The Bush Administration did not specify how it would reduce the U.S. arsenal from around 6,000 warheads to the lower level of 2,200 operationally deployed warheads, although it did identify some force structure changes that would account for part of the reductions. Specifically, after Congress removed its restrictions,17 the United States would eliminate the 50 Peacekeeper ICBMs, reducing by 500 the total number of operationally deployed ICBM warheads. It would also continue with plans to remove 4 Trident submarines from service, and convert those ships to carry non-nuclear guided missiles. These submarines would have counted as 476 warheads under the START Treaty’s rules. These changes reduced U.S. forces to around 5,000 warheads on 950 delivery vehicles in 2006; this reduction appears in Figure 2. The Bush Administration also noted that two of the Trident submarines remaining in the fleet would be in overhaul at any given time. The warheads that could be carried on those submarines would not count against the Moscow Treaty limits because they would not be “operationally deployed.” This would further reduce the U.S. deployed force by 200-400 warheads.The Bush Administration, through the 2005 Strategic Capabilities Assessment and 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review, announced additional changes in U.S. ICBMs, SLBMs, and bomber forces; these include the elimination of 50 Minuteman III missiles and several hundred air-launched cruise missiles. (These are discussed in more detail below.) It is not clear whether these changes would reduce the number of operationally deployed warheads enough to meet the Treaty limit of 2,200 warheads. The outcome depends on how many warheads are carried by each of the remaining Trident and Minuteman missiles and how many bomber weapons remain in the U.S. arsenal. The United States could reach the Treaty limits by reducing the number of delivery vehicles, by reducing the number of warheads carried on each delivery vehicle, or by altering the way it counts the warheads on its delivery vehicles.