Behavioral Indicators Offer Insights for Spotting Extremists Mobilizing for Violence

- 5 pages

- For Official Use Only

- July 22, 2011

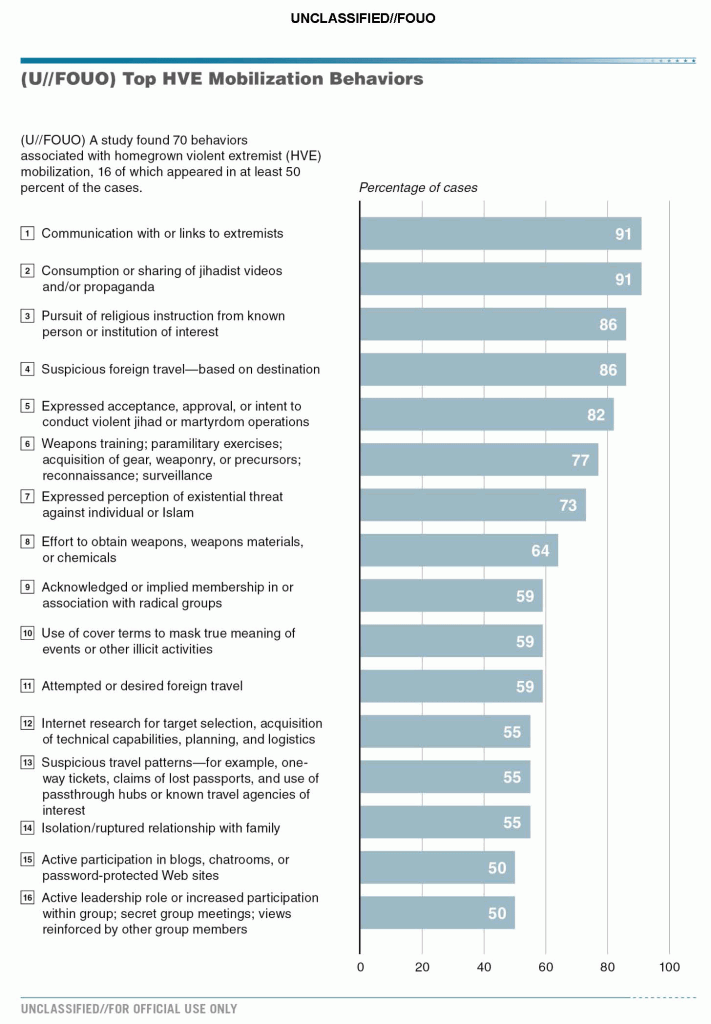

(U//FOUO) A US Government interagency study of homegrown violent extremists (HVEs) revealed four major mobilizing patterns shared by a majority of HVE cases between 2008 and 2010, providing officials with an emerging picture of distinct behaviors often associated with an individual mobilizing for violence. These four patterns—links to known extremists, ideological commitment to extremism, international travel, and pursuit of weapons and associated training—repeatedly appeared in the case studies, reinforcing initial assessments of potential trends. Awareness of the patterns can help combat the recent rise in these cases while providing a data-driven tool for assessing potential changes in the HVE threat to the Homeland.

- A six-month interagency assessment of the mobilization process through which radicalized individuals progress toward violence was initiated in 2010. This assessment specifically sought to identify facets of the mobilization process and develop new, data-driven approaches that a could improve our ability to help policymakers and law enforcement officials detect and counter potential HVEs.

- The assessment entailed a comprehensive review of 22 case studies involving the mobilization of 27 HVEs. Case studies involving law enforcement operations were excluded from review in an effort to examine mobilization independent of law enforcement influence.

- The individuals referenced in this Spotlight lived or operated primarily in the US at some time during their radicalization. For consistency, they are referred to here as HVEs, although four of them later acted at the behest of a foreign terrorist organization and are therefore considered former HVEs.

(U//FOUO) Mobilization-Based Approach Focuses on Behavioral Indicators

(U//FOUO) A mobilization-based approach to identifying extremists poised for violence focuses on behavioral indicators that are observable and well suited for analytic assessments using objective criteria. By

contrast, efforts aimed at detecting indicators of radicalization often rely on subjective assessments of factors—such as an individual’s mental state, degree of ideological convictions, and personal motivations—that do not readily lend themselves to data-based analysis.(U//FOUO) Four HVE Mobilizing Patterns

(U//FOUO) Four prominent, observable behavioral patterns of HVEs who have mobilized for violence emerged in our review of the case studies.

Links to Connected Extremists

(U//FOUO) Contact with individuals tied to terrorist organizations is one of two indicators that appeared most often in our case studies. This finding is consistent with earlier assessments—based on past cases of domestic and transnational terrorism—that exposure to an extremist with established ties to a terrorist group can be a useful indicator of a radicalized person moving toward violence.

- More than 90 percent of our subjects either communicated directly or had some type of contact with connected extremists as part of their mobilization to violence.

- Sharif Mobley, arrested in Yemen in 2010 for ties to al-Qa‘ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), asked Anwar al-Aulaqi to take him on as a student when he decided to leave the US for Yemen in 2008

- Faisal Shahzad, who in 2010 attempted to detonate an explosive device in Times Square, first had contact with Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) through a friend and TTP facilitator whom he met while they were university students in the US.

Ideological Commitment to Extremism

(U//FOUO) Indicators of ideological commitment also appear frequently in HVE reporting. One of these behaviors—“watching or sharing jihadist videos”—was the second of the two most prevalent indicators noted in the study. Ideological commitment behaviors were observable but at times only in a virtual environment.

- More than 90 percent of the cases involved HVEs who either watched or shared jihadist videos or other propaganda. Just under 90 percent involved HVEs pursuing religious instruction from a person or institution associated with extremist causes. Roughly 80 percent of the cases reflected an individual’s acceptance or approval of violent jihad or martyrdom operations or an intent to engage in them. In a slightly smaller percentage of cases, the HVEs perceived an existential threat against Islam.

- American al-Shabaab commander Omar Hammami was a member of a nonviolent Salafi group until he moved to Canada in 2005. He began to doubt his nonviolent perspective on Islam after Canadians confronted him with questions about US actions in Afghanistan and Iraq. Hammami turned to online forums for guidance and became attracted to and influenced by extremist rhetoric.

International Travel

(U//FOUO) Travel or attempted travel in pursuit of violent jihad was a recurring factor in the HVE cases, also supporting earlier assessments of the importance of foreign travel for violent extremists.

- Almost 90 percent of our subjects traveled to places with a significant extremist population or to a foreign location explicitly to pursue violent jihad. Of the three people in our cases who did not travel, two made serious attempts to do so.

- Najibullah Zazi, who in 2010 pled guilty to terrorism charges, traveled in August 2008 to Pakistan where he attended an al-Qa‘ida training camp and discussed targets with al-Qaida operatives.

- Abdel Hameed Shehadeh, arrested in October 2010 for providing false statements about his attempted travel to Pakistan to join a terrorist group, tried to travel there in 2008 but was denied entry.

Search for Weapons or Weapons-Related Training

(U//FOUO) Mobilizing extremists in our case studies often sought weapons or weapons-related training. This more tactically focused aspect of attack planning also entailed online research to acquire technical capabilities, select targets, and plan logistics.

- Almost 80 percent of our subjects pursued weapons training, paramilitary exercises, or the acquisition of related equipment as part of their mobilization. More than half also conducted Internet research to plan their attacks.

- Tarek Mehanna and his coconspirators, charged in October 2009 with providing material support to terrorists, had multiple conversations about obtaining automatic weapons and randomly shooting people in a shopping mall. The conversations covered the logistics of a mall attack, including coordination, weapons needed, and the possibility of attacking emergency responders.

(U//FOUO) Checklist Approach to Mobilization Indicators Most Likely To Backfire

(U//FOUO) The wide array of indicators reflected in the case studies, coupled with the variety of US organizations that appear best placed to detect specific signs, cautions against adopting a checklist-like mentality in countering the HVE threat. Simplistically interpreting any single indicator as a confirmation of mobilization probably will lead to ineffective and counterproductive efforts to identify and defeat HVEs.

- HVEs in more than 70 percent of the cases displayed behaviors in all four categories. Viewed individually, however, these indicators may not predict mobilization. Numerous individuals who travel internationally to areas of concern, for example, do not attempt to stage attacks or otherwise support terrorist groups.

- Focusing exclusively on a single indicator, such as commitment to ideology, also may alienate HVEs and give them additional grievances that could speed mobilization rather than stop it.

(U//FOUO) Finding combinations of indicators offers the best approach to countering HVEs. Identifying such combinations in a timely manner requires collaboration that taps the capabilities of federal, state, and local government agencies and their nongovernment partners.

- Given the variety of indicators, it is unlikely that any single organization will have access to information on all behaviors that, collectively, could portend violence.

- To succeed, a collaborative approach must entail effective and timely communication among the various people and organizations best placed to detect different mobilizing indicators, allowing each to contribute unique perspectives to a broader composite picture of key mobilizing trends. That broader picture in turn can provide individual people and organizations with real-time insights into the US Government’s current understanding of HVE trends.

- For example, 55 percent of our subjects conducted online research as part of their attack planning—actions most vulnerable to detection. Those who detect on-line research, however, are unlikely to see indicators of withdrawal from established social networks, which also appeared in 55 percent of the case studies. Local-level contacts such as school officials are most likely to detect these types of indicators.