A map of school shootings throughout the U.S. from January 2008-August 2013 included in a report from the Los Angeles Joint Regional Intelligence Center.

Public Intelligence

Law enforcement has struggled in recent years with the issue of mass shootings and how to provide the public with adequate ways to detect and possibly catch shooters before they strike. School shootings, in particular, have vexed criminal analysts trying to help school officials ensure the safety of their students by identifying at-risk individuals that might engage in acts of violence. This has led to some strange and seemingly arbitrary speculations about the nature of school shooters.

A 2009 document released by the FBI and the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime titled “The School Shooter: A Quick Reference Guide” is one example of this sort of speculation. The guide warns that “repeated viewing of movies depicting school shootings” such as Zero Day and Elephant could indicate a fascination with school shootings. According to the guide, school shooters often exhibit “violence in their own writings, poems, essays, and journal entries” and have an interest in violent movies. Law enforcement and school officials concerned about a student are encouraged to monitor the subject’s online videos, blogs, and social networking activities to look for signs of grief and desperation.

Another guide produced in 2006 by the Regional Organized Crime Information Center contained similarly broad and speculative observations that could likely be applied to large swaths of the student body at your local high school. In a section on “warning signs” of a school shooter, the guide lists an “attitude of superiority” and “exaggerated sense of entitlement.” The guide goes on to say that school shooters are often “fans of violent media, especially first-person shooter games” and “social outcasts who pride themselves on exclusion from popular circles.”

Analyzing School Shootings

Moving away from these basic speculations, law enforcement has expanded its efforts to embrace statistical analysis in the hopes of discovering common attributes among school shooters and mass shootings generally. Over the last year, fusion centers in several states have released studies, deriving useful information from aggregate analysis that can actually help the public understand the phenomenon of school shootings and what drives people to engage in this sort of seemingly random violence.

A statistical analysis of school shootings released in August by the Los Angeles Joint Regional Intelligence Center (LAJRIC) studied school shootings throughout the U.S. from January 2008 to August 2013. In that five-year span, there were 85 school shootings that took place in 29 states, a majority of the country, with most states experiencing between one and three incidents over the last five years. California ranked highest with 18 incidents, followed by Michigan and Tennessee. The majority of school shootings, about 52%, took place at high schools, with the rest equally distributed between colleges/universities and elementary/middle schools.

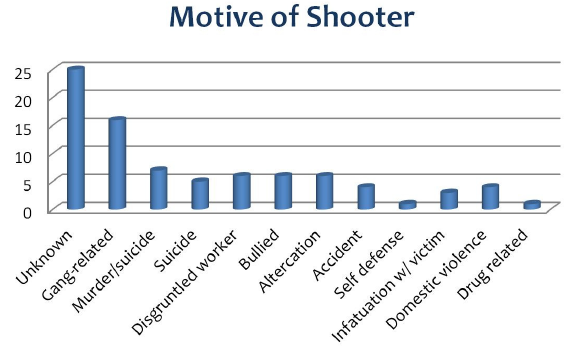

A chart from the Los Angeles Joint Regional Intelligence Center study of school shooting incidents from January 2008-August 2013 depicts motivations for school shooters.

These shootings were perpetrated by 97 people, almost entirely male, with only 4% being perpetrated by females. Most of the shootings involved the use of small arms and only 11% involved the use of multiple weapons. Less than half of the shootings (46%) were committed by current or former students at the school and only 8% were committed by current or former employees. Significantly, at least 40% of school shooters during the five-year period had no connection to the school where the attack occurred.

Half of the victims of school shootings were intentionally targeted by the gunman with only 21% being killed or wounded due to indiscriminate gunfire. In 57% of the incidents the perpetrator directly knew the victims. The majority of the perpetrators were between 16‐18 years old (31%) with the second largest group being 13‐15 year old (23%). Demographics and motivations for school shooters vary widely, with most being perpetrated for unknown reasons. Gang-related shootings happening in and around school campuses account for nearly three-times the amount of incidents as murders/suicides and retaliation for bullying. In fact, only 27% of school shooters commit suicide or are killed by authorities. Most school shooters (61%) end up being arrested after having killed one or more victims.

Digging Deeper

A similar report released in March by the Massachusetts Commonwealth Fusion Center (CFC) studied school shootings from 1992-2012, obtaining significantly different results from the study conducted by LAJRIC due to the use of more stringent criteria. The CFC study found that 80% of school shooters were current or former students at the targeted school, as opposed to the figure of 40% in LAJRIC’s report. CFC found that 40% of perpetrators used two or more weapons and that 43% entered the building normally with their weapons concealed. According to the CFC’s findings, most school shootings (42%) occur in the morning between 7-11:30 AM. One particularly interesting finding from the CFC report is the high number of victims from a few specific incidents versus the relatively low number of victims from most school shootings. Though 87% of incidents resulted in 0-3 fatalities, CFC found that three incidents accounted for 45% of all fatalities during the period.

The CFC report notes that a history of mental health issues was cited in 28% of school shootings as a motivating factor. Other common motivations include “difficulty coping with significant losses or personal failures” or specific grievances, including bullying. Both the CFC report as well as an analysis released last year by the New Jersey Regional Operations Intelligence Center (NJROIC) found that school shooters often indicate their intentions to others prior to the incident. The CFC found that in 33% of incidents one or more people knew directly of some aspect of the perpetrator’s intentions through direct statements or online posts using social media. The NJROIC analysis states that “the majority of students who have conducted plots or attacks against their schools have publicized their anger or intentions through the use of social media” and provides several examples of school shootings that followed online threats. For example, the perpetrator of a 2011 school shooting in Omaha, Nebraska that resulted in the death of a school administrator posted a Facebook update prior to the shooting that read:

“Everybody that used to know me, I’m sorry but Omaha changed me and fucked me up. And the school I attend is even worse. You’re gonna here [sic] about the evil shit I did but that fucking school drove me to this. I want you guys to remember me for who I was before this. I greatly affected the lives of the families ruined but I’m sorry. Goodbye.”

Likewise, the perpetrator of a school shooting at an Ohio high school in February 2012 that resulted in the deaths of three students posted a poem filled with violent imagery on Facebook several months prior that ended with the phrase: “Die, all of you.” If caught in time, these indicators can actually help stop attacks from happening. A plot to bomb a Utah high school in early 2012 was foiled after one of the potential perpetrators sent a text message to another student stating “If I tell you one day not to go to school, make damn sure you . . . are not there.” The text messages went on to document parts of the teens’ alleged plot to steal an airplane following the attack and flee the country: “I get the feeling you know what I’m planning . . . explosives, airport, airplane. We ain’t gonna crash it, we’re just gonna kill and fly our way to a country that won’t send us back to the U.S.” Due to the text messages being reported to authoirities, the plan to attack the school was thwarted. Investigators said they later found detailed blueprints of the school and bomb-making materials at the suspect’s home.