American, British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand (ABCA) Armies Program

- ABCA Publication 369, Edition 2

- 103 pages

- July 1, 2011

SFCB has come to play an increasingly important role in each of our armies over the last decade and will undoubtedly feature in operations spanning the spectrum of conflict in the future. Its affect on organization, training, equipping and doctrine has been felt to a greater or lesser extent by each of us and will help define recent conflicts and their effects. However, SFCB cannot be done in isolation. What must be borne in the military planner‘s mind from the outset is that SFCB is a part of the wider SSR campaign and as a consequence must be part of a comprehensive approach. Furthermore, if coalition partners are present, an extra layer of complexity is present and must be planned for. Failure to take these two aspects into account runs the risk of failure at worst or a fragmented HNSF as a result, at best. This handbook aims to assist the military planner in their approach to SFCB. It is aimed at both commanders and staff officers, primarily on brigade and divisional staffs, although it also has utility for those charged with training, mentoring and advising HNSF forces at the tactical level.

…

UNDERSTANDING CULTURE AND DEVELOPING TRUST

Introduction

1. Failure to take culture and the building of trust seriously during SFCB could potentially lead to mission failure. For the purposes of this handbook culture is defined as the set of opinions, beliefs, values, and customs that forms the identity of a society. It includes social behavior standards (e.g., how men relate with women, children relate with adults), language (standard of speech), and religion (standards on how man relates with his mortality and creation). Trust is defined as that firm reliance on the integrity, ability, or character of a person or unit. Trust is both an emotional and logical act, which in practice is a combination of both. In assessing the HN culture ABCA nations should bear in mind from the start other cultures‘ perception of our predominantly Western lifestyle. In addition ABCA nations should beware not to fall into the trap of imposing their own culture, particularly their military culture, on HN forces where this may not be appropriate.

2. Recent Campaigns. Recent campaigns have seen ABCA forces repeatedly deploy to conduct SFCB in parts of the world quite different to their own. Not only do these nations often speak languages that are relatively rarely spoken or studied in ABCA nations, they also have very different cultures. These cultural differences include different religions, ethnic variances, tribal networks, or even comprehensive codes of practice, such as Pashtunwali1 in Afghanistan.

3. Implications of Cultural Issues upon SFCB. There are three major implications of conducting SFCB.

a. Culture Shock. ABCA forces need to understand the cycle through which they may pass during training and deployment when confronted by a different culture. This self-awareness and suggested mitigating activity should serve to reduce the impact of culture shock on the overall campaign.

b. Cultural Sensitivity in the conduct of SFCB. An understanding of the importance of cultural sensitivity, heeding local customs, values and norms, is vital when conducting SFCB. Even more important is the development of trusting relationships between ABCA and indigenous forces. Time and energy must be invested in these if they are to flourish.

c. Improved operational effectiveness by leveraging HNSF Cultural Understanding. HNSF generally have an understanding, both of local culture and the broader human terrain that ABCA nations are unlikely ever to rival, even after repeated tours. HNSF therefore offer ABCA nations an opportunity to understand the human terrain in which they are operating that will otherwise be lacking. SFCB cannot be conducted in isolation.

…

ANALYZING THE HNSF REQUIREMENTS

Introduction

1. Building HN security force capability and capacity should begin with an overarching analysis of requirements, existing capabilities, capacity and constraints, including a thorough consideration of cultural, political and economic factors.

2. Each situation will differ depending upon the level of conflict in the Host Nation and the existing capabilities and capacity of their security forces. The complexity and difficulty of conducting SFCB increases dramatically when working in a failing or failed state. Under such conditions, the key operational level security sector organizations, particularly Defense and Interior ministries, may not be present or effective.

3. Analysis must start from an understanding of the operational environment, the required end-state and taking into account the region‗s needs and concerns. Analysis should determine the requirements for force development, training, sustainment, unit and logistical distribution, deployment of forces, and equipment acquisition for each type of security force.

4. In the absence of a Joint Interagency Multinational process, the application of the military estimate or decision making process may serve as a useful start point. However, it is important that this is not carried out in isolation and is part of a comprehensive approach.

…

Evaluating Campaign Progress

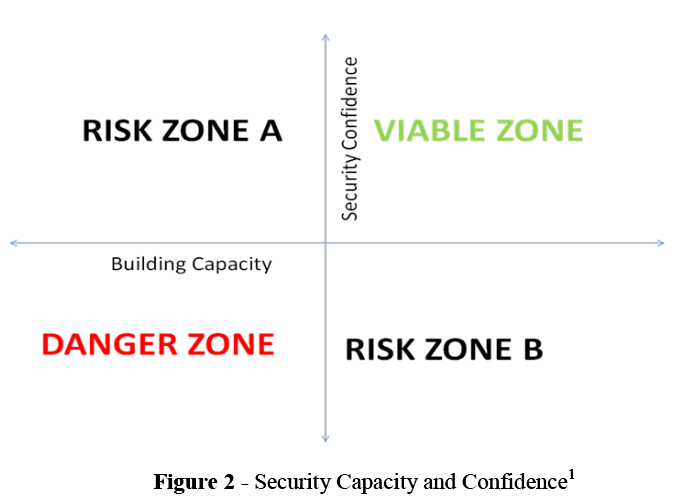

17. The previous discussion has focused on developing measures of assessment for application across the tactical and operational spectrum. Assessing overall progress at the campaign level to understand whether the accumulative effects of our actions are indeed contributing to campaign success are just as important. As outlined earlier CEA is derived from an appreciation of the accumulative results of the MoP and MoE, set against the wider contextual analysis of the environment. Being able to monitor and track progress at this level requires a method for mapping a complex range of variables which contribute to a secure environment. Figure 2 is a suggested means with which to track overall progress made in the delivery of a security effect through HN SFCB.

18. Clearly security capacity in the upper end of the scale would be ideally matched with a high level of community confidence thus representing a viable security condition. Risk Zone A would represent a high level of security confidence among the target community but with low security force capacity. This might be indicative of regions which have been typically calm and relatively unaffected by the adversary – the risk being that this could change. Risk Zone B is high security force capacity but low security confidence and may point to other factors as the cause of poor security confidence, perhaps corrupt security force leadership. Clearly low capacity and low confidence is an unviable security condition.