The following Army Techniques Publication is an update to a previous Army Tactics, Techniques and Procedures publication titled “Law and Order Operations” released in June 2011. A version of the document from January 1945 (FM 19-10) was titled “Military Police in Towns and Cities” and was “designed to furnish a guide for officers and enlisted men assigned the mission of patrolling civil communities.”

ATP 3-39.10 Police Operations

- 252 pages

- January 2015

ATP 3-39.10 is aligned with FM 3-39 and the Military Police Corps Regiment operational doctrine. It provides guidance for commanders and staffs on police operations. Police operations support decisive action tasks (offensive, defensive, and stability or defense support of civil authorities [DSCA]). This manual emphasizes policing capabilities necessary to establish order and subsequent law enforcement (LE) activities that enable successful establishment, maintenance, or restoration of the rule of law. While this manual focuses on the police operations discipline and its associated tasks and principles, it also emphasizes the foundational role that police operations, in general, play in the military police approach to missions and support to commanders. The police operations discipline is the lead discipline of the military police, shaping the approach of military police and providing the foundation on which the other military police disciplines are conducted.

ATP 3-39.10 is written for Army military police personnel conducting police operations while assigned to military police brigades, battalions, companies, detachments, United States Army Criminal Investigation Command (USACIDC) elements, military police platoons organic to brigade combat teams, and provost marshal (PM) staffs. It applies to military police commanders, staffs, functional cells, and multifunctional commanders and staff elements at all echelons tasked with planning and directing policing and LE activities. This manual describes police operations executed across the range of military operations and operational environments, with specific emphasis on police station operations and associated LE patrol activities.

…

Police operations have historically been understood to consist of LE missions supporting U.S. military commanders and their efforts to police our military personnel, civilians, and family members working and residing on U.S. military bases and base camps. Bases and base camps refer to any U.S. military installation, base, or other location within the United States and enduring installations, bases, or other locations outside the United States employed to support long-term military commitments and/or serve as power projection platforms. U.S. Army doctrine has not historically focused on police operations outside of LE support to bases and base camps. Police operations support to the operational commander and the capabilities inherent within LE organizations have been growing in relevance to the Army over the past decade. Recent conflicts and the nature of the threat within the operational environment have increased the relevance of police operations and LE capabilities in support of Army operations. The applications of police operations and the requirements for Army LE personnel to conduct these operations have grown tremendously as nation building and protracted stability operations have demonstrated the need for civil security and civil control as critical lines of effort within the larger effort to transfer authority to a secure and stable HN government.

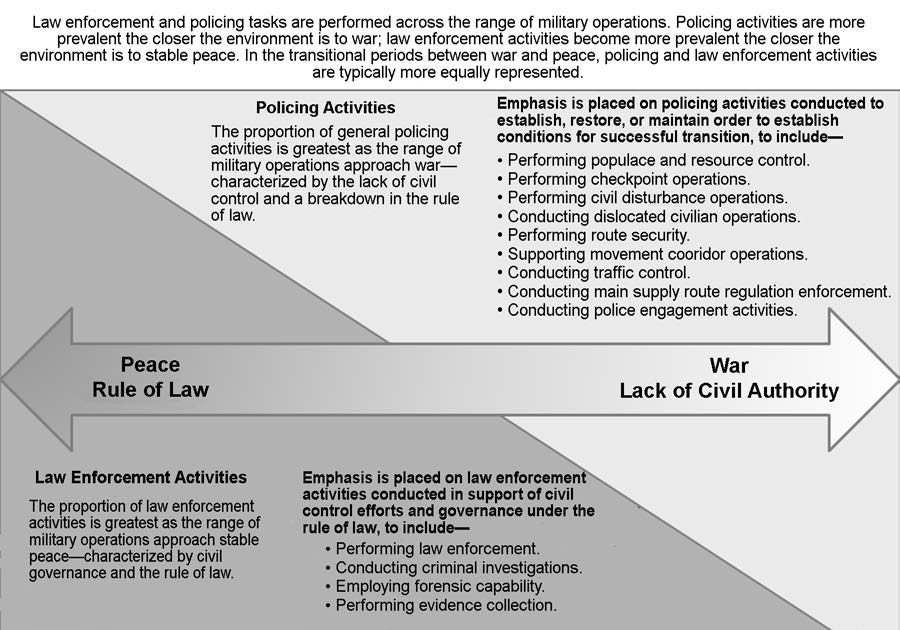

Lessons learned from recent conflicts, coupled with task analysis conducted by USAMPS, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, have resulted in an expanded doctrinal framework and understanding of police operations. The expanded framework does not establish new tasks within the police operations discipline, but identifies and documents missions and tasks in the revised doctrine that have historically been conducted by military police. Recent updates to military police doctrine establish police operations as the primary military police discipline, shaping the actions and perspectives of military police in the conduct of military police disciplines. These updates describe police operations within the context of two activities—policing and LE. Policing activities are general actions aimed at establishing order and stability within an area of operations (AO); LE activities are tied to the rule of law and require specific training and authority for the element or personnel performing the actions. While military police are uniquely qualified to conduct policing, these activities do not require personnel specifically trained for LE activities. LE activities require specific training and may only be conducted by LE personnel (military police, USACIDC special agents [SAs], or other trained and certified LE personnel).

Beyond support to bases and base camps, the requirement for military police capabilities in training and supporting HN police is the most visible and resource-intensive police operations activity. Additionally, maneuver commanders recognize several key LE enablers that greatly enhance and contribute to mission success, including—

– Expertise in evidence collection that is critical to successful site exploitation and criminal prosecution.

– Biometric collection, biometric identification capabilities, and modular forensic laboratories.

– Identification of critical civil information regarding the criminal environment, the HN police capability and capacity, and the local population, which is obtained through integrated police intelligence operations.Military police capabilities are invaluable to the maneuver commander whether conducting LE activities in support of bases and base camps, supporting protection requirements, maintaining and restoring order in an effort to stabilize an AO, providing training and support to HN police, controlling populations, or supporting humanitarian relief operations.

…

1-16. Policing is characterized by the restrictive rules of engagement or rules for the use of force, designed to limit the application of force upon a population or group. This restraint differentiates policing from conventionally focused military operations. Military police Soldiers are trained to conduct missions using the minimal force necessary to accomplish their task. This inherent mind-set of the de-escalation of violence and restraint makes military police Soldiers highly suited to policing tasks. Policing is a critical step in establishing civil security as a precursor to establishing civil control and the transition to self-governance by the rule of law. Policing tasks conducted with no LE purpose can be conducted by any Army Soldier with appropriate training.

Note. The corrections mission is not considered an LE function. Corrections operations are the exception to the rule in that any Soldier with the appropriate training and supervision can conduct policing tasks with no LE purpose. The corrections mission, as distinguished from detention operations, is its own leg of the criminal justice system (police, corrections, courts). Corrections operations require specially trained military police (military occupational specialty 31E) or other personnel who are trained in the technical and legal requirements associated with conducting corrections operations as an integral part of the criminal justice system, operating under the rule of law. (Detention operations are described in FM 3-39.)

…

BROKEN-WINDOW THEORY

2-9. The broken-window theory of policing originated in 1982 and was first proposed in the article, “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety,” by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. Broken-window policing stresses eliminating indicators of minor crimes (and subsequently, the crimes themselves) and disorder and addressing crime-conducive conditions based on the theory that allowing minor problems (broken windows, trash accumulation, public nuances) encourages vagrants, gangs, drugs, and other more serious problems to take root and creates public fear. Broken-window policing proposes that quickly and consistently addressing neighborhood problems (including petty crimes such as vandalism) discourages future incidents. The theory proposes that petty criminals left unchecked will gradually increase their activity and eventually begin committing more serious criminal acts.

2-10. Previous policing strategies tended to focus on major crimes and criminal problems, ignoring what personnel deemed minor peripheral problems. Police personnel saw areas with significant indicators of petty criminal behavior and crime-conducive conditions as unimportant and not relevant to their function of fighting crime. The broken-window approach encouraged partnership between the police and the community to address small problems before they became large problems. Police agencies conducting broken-window policing focus efforts on identifying and correcting crime-conducive conditions and identifying and detaining individuals committing minor crimes and causing disruptions. Police also encourage (and cite when necessary) property owners to clean up and repair their property, resulting in a feeling of community empowerment as a means to help reduce criminal and disruptive activity.

2-11. Broken-window policing received mixed results; therefore, the cause-and-effect relationship between this approach and the results is not universally accepted. This policing strategy can be implemented relatively easily within the military community due to the command structure and influence that can be leveraged across the AO.

…

Special-Reaction Teams

2-71. An SRT is a specially trained and equipped reaction force integral to contingency plans for bases and base camps responding to a major disruption or special threat situation. Commander’s organize, equip, and train the SRT according to AR 190-58. Commanders should ensure that trained and certified SRT capability exists within each military police company. The SRT is one of the most technical and highly trained LE assets. The SRT has the capability to neutralize, through control and selective fire functions, persons who, if not removed by fire, pose an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury against others. ATP 3-39.11 provides guidance for training, equipping, and employing SRTs. Special threat situations where SRTs can be employed include—

– Precision high-risk entry for barricaded persons.

– Dangerous suspect apprehensions.

– Counter sniper operations.

– Precision offensive sniper operations.

– LE searches and raids.

– Support to protective services.

– Precision fire and overwatch capabilities.

– Close quarters battle tactics instruction to HN police.…

Special-Reaction Team

3-75. The SRT elements, sometimes referred to as special weapons and tactics units within the civilian community, provide specially trained, armed, and equipped response capability to contain and neutralize special threats. (See ATP 3-39.11.) They are a critical part of many crisis response plans. The SRTs within the military police are rarely dedicated assets due to resource constraints. The SRT members are typically Army LE personnel who perform other LE tasks until a situation presents itself that requires an SRT capability. Army LE operating within the United States may partner with civilian LE agencies for SRT support capability when sufficient civilian capability exists. PMs, through the commander of the supported bases and base camps, will document this requirement through support memorandums of agreement with the supporting civilian LE agency that have federal exclusive, concurrent, or proprietary enforcement authority on installations.

3-76. Military police SRT capabilities are required for LE and antiterrorism efforts in support of mature bases of operation in-theater. As U.S. military bases mature within a joint AO, military police SRTs provide a dedicated response capability to neutralize and contain internal criminal threats and external terrorist threats. Military police SRT assets may be used initially in support of HN LE efforts when U.S. forces are tasked with building civilian police capability and capacity within an HN. As soon as practical, SRT capability should be developed and maintained within the HN police structure. Training for SRT personnel is provided by USAMPS.

Biometrics

3-77. Biometrics is the process of recognizing an individual based on measurable anatomical, physiological, and behavioral characteristics (JP 2-0). These characteristics are useful for tracking individuals, making positive identifications, establishing security procedures, or using as tools to detect deception based on measurable biological responses to stimulus. Biometric data can be used for protection and security efforts, contributions to biometric-enabled intelligence activities, and evidence in investigations and criminal prosecution. Matching biometric data from persons against forensically collected biometrics correlates a person to a place or activity. The following are the major types of biometric data used by police and intelligence collectors:

– Personal identification data. Biometric collection and identification devices use biological information (fingerprints, voiceprints, facial scans, retinal scans) to match an individual to a source database. The identity of a specific individual can be identified from the target population during screening.

– Data that indicates source truthfulness. Devices such as voice stress analyzers and polygraphs are useful in determining a subject’s truthfulness. The USACIDC commanding general, in coordination with the Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Plans, exercises overall Army staff responsibility for the DA Polygraph Program and policy guidance with respect to using the polygraph in criminal investigations. The Army Deputy Chief of Staff for intelligence promulgates policy on the use of polygraph and credibility assessment for intelligence and counterintelligence applications in AR 381-20.…

Investigative Stops (Terry Stops and Frisks)

4-70. A Terry Stop (Terry versus Ohio, 1968) (also known as an investigative stop) is the brief detention of a person when Army LE personnel have reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. Reasonable suspicion is a lesser belief than probable cause but, like probable cause, is based on the totality of the circumstances. The experience of Army LE personnel; the crime conditions (such as a high-crime area); the mannerisms, dress, and activities of the detainee; and the time of day are factors when considering the totality of the circumstances for a Terry Stop.

4-71. The Terry Stop allows for a frisk of the detainee for the safety of Army LE personnel. However, the frisk is not automatic and should only be performed when there is a reasonable belief that the person is armed and presently dangerous. The frisk does not rise to the level of a body search. A frisk consists of a pat down of the outer clothing; the inner clothing is not touched and personnel should not conduct a pocket search unless a weapon is found. Within the context of LE officer safety and frisks associated with Terry Stops, weapons are defined very broadly. Many objects can be used as and considered a potential weapon, (a screwdriver; scissors; other sharp, heavy, or dense objects). If other contraband is discovered during the conduct of a lawful frisk, Army LE personnel may seize that contraband. The Terry Stop can turn from a detention to an apprehension if probable cause develops that a crime has occurred or will be committed by the detained person.

4-72. If, in the course of a lawfully conducted frisk of an individual’s outer clothing, an Army LE officer feels an object with a contour and mass making its identity immediately apparent as contraband, the officer may seize the object. In this instance, there is no unauthorized invasion of privacy; LE personnel were already acting within established constraints to search for weapons. The contraband may be seized without a formal search authorization and would be justified by the same practical considerations that inhere in the plain-view context (see Minnesota versus Dickerson, 1993). This action is also known as plain-feel doctrine.

4-73. Army LE personnel cannot arbitrarily conduct a search based on a hunch or without proper authority. The following paragraphs describe the requirements to conduct a search, whether granted by an authorization or by consent of the individual having control over the area or property to be searched.