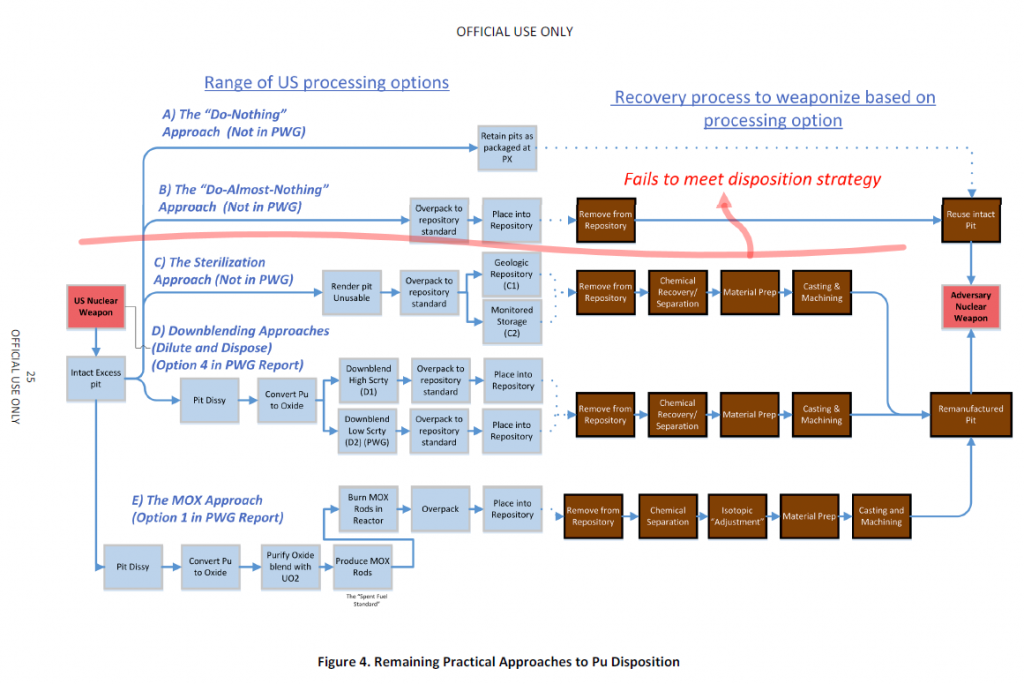

The Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement (PMDA) calls for the United States and Russia to each dispose of 34 metric tons (MT) of excess weapon-grade plutonium by irradiating it as mixed oxide fuel (MOX), or by any other method that may be agreed by the Parties in writing. The MOX disposition pathway is a realization of the spent fuel standard (SFS) as envisaged in the 1994 National Academy of Sciences (NAS) review that recognized the value of physical, chemical, and radiological barriers to future use of the material in nuclear weapons whether by state or non-state actors. The decision to pursue the MOX pathway using light water reactors in combination with immobilization using a can-in-canister approach was adopted by the United States Department of Energy (DOE) after review of 37 different pathways for disposition in 1997. Since that time, the situation has evolved in a number of significant ways:

• Nonproliferation policy has been increasingly focused on potential threats from non-state actors, which increases the sense of urgency for timely disposition and potentially offers greater flexibility in the final form of the material to prevent future use;

• The cost of the MOX approach has increased dramatically compared to early estimates;

• A disposition alternative not available in the nineties has been successfully demonstrated in support of the closure of Rocky Flats and other projects—downblending or dilution of PuO2 with adulterating material and disposal in the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP).

The Dilute and Dispose option can be thought of as substituting geologic disposal for the self-protecting radiation field and physical protection of spent fuel casks, and the dilution with adulterants as the chemical barrier. The Scoping Comment Summary from the Draft Surplus Plutonium Disposition Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) noted: “DOE believes that the alternatives, including the WIPP Alternative, analyzed in this Surplus Plutonium Disposition SEIS provide protection from theft, diversion, or future reuse in nuclear weapons akin to that afforded by the Spent Fuel Standard.” The review team concurs with this assessment and believes that the Dilute and Dispose approach meets the requirements for permanent disposition, but recognizes that this assertion will ultimately be subject to agreement with the Russians, and that the decision will be as much political as technical.

The primary focus of the Red Team was a comparison of the MOX approach to a Dilute and Dispose option (and some variants of each), in light of recently published cost comparisons. As discussed in the Introduction to this document, consideration was given to other options such as fast reactor Pu metal fuel or borehole disposal, but these options have large uncertainties in siting, licensing, cost, technology demonstration, and other factors, so the Red Team concluded early that they did not offer a suitable basis for near term decisions about the future of the program. Were fast reactors to become part of the overall U.S. nuclear energy strategy (as they are in Russia), or if a successful research and development program on borehole disposal led to siting of a disposal facility, these options could become more viable in the future.

Analyses of the MOX and Dilute and Dispose options have been carried out at various times, by various parties, with differing degrees of access to relevant information, and with varying assumptions about conditions over the long duration of the program. The Red Team’s analysis focused on annual funding levels (during both construction and operations), risks to successful completion, and opportunities for improvements over time that could accelerate the program and save money. For comparison purposes, the Red Team describes a relatively optimistic view of the MOX approach [adjusted somewhat to account for a dispute in the present status of the MOX Fuel Fabrication Facility (MFFF) project], and compares it to a relatively conservative version of the Dilute and Dispose alternative.

The Red Team concluded that if the MOX pathway is to be successful, then annual funding for the whole program (MFFF plus other activities that produce feed material and support fuel licensing and reactor availability) would have to increase from the current ~$400M per year to ~$700M-$800M per year over the next 2-3 years, and then remain at $700M-$800M per year until all 34 MT are dispositioned (all in FY15 dollars). To be successful, the overall effort would need to be clearly driven with a strong mandate to integrate decision making across the sites and across DOE programs and organizations. At this funding level, operations would only commence after as much as 15 more years of construction and ~3 years of commissioning.

…