CENTER FOR LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS

CENTER FOR LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS

- 236 pages

- September 1, 2010

The Domestic Operational Law (DOPLAW) Handbook for Judge Advocates is a product of the Center for Law and Military Operations (CLAMO). First published in April of 2001, it was the first of its kind. Designed as a resource for operational lawyers involved in domestic support operations, its publication was indeed timely. After the events of September 11, 2001, and more recently, Hurricanes Katrina in 2005 and Ike in 2008, the Handbook continued to meet a growing need for an understanding of the legal issues inherent in such operations. As with the original publication of the Handbook, this update would not have been possible without the tireless efforts of countless active, reserve, and National Guard judge advocates who participate in these unique operations on an ongoing basis.

The contents of this Handbook are based on statutes, Executive Orders and Directives, national policy, DoD Directives, joint publications, service regulations and field manuals, and lessons learned by judge advocates. The Handbook is not a substitute for complete references. Indeed, as this update goes to publication, changes in these references are being discussed and in some cases, in the process of completion. Judge Advocates advising in this area of the law should monitor developments in this area closely as the landscape continues to evolve. Further, upon release, the new FM 3-28, Civil Support Operations, should be added to the bookshelf of Judge Advocates and operators alike that may be called to support operations in the Homeland. It provides an excellent overview of the subject and should be read in its entirety.

…

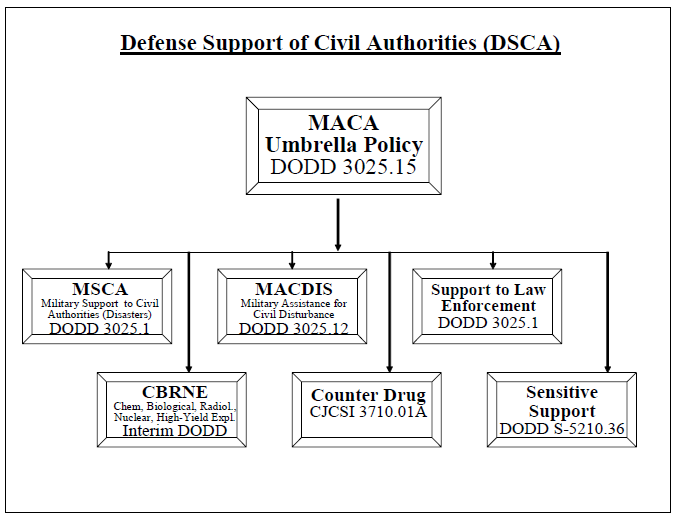

CIVIL DISTURBANCE OPERATIONS

KEY REFERENCES:

• 10 U.S.C. § 331-335 – The Restoration Act (Formerly known as “The Insurrection Act”)

• 10 U.S.C. § 2667 – Leases: Non-Excess Property of Military Departments

• 18 U.S.C. § 231 – Civil Disorders

• 18 U.S.C. § 1382 – Entering Military, Naval, or Coast Guard Property

• 18 U.S.C. § 1385 – The Posse Comitatus Act (PCA)

• 28 U.S.C. § 1346, 2671-2680 – The Federal Tort Claims Act

• 31 U.S.C. § 1535 – Agency Agreements

• Executive Order 12656 – Assignment of Emergency Preparedness Responsibilities

• EO 13527 – Establishing Federal Capability for the Timely Provision of Medical Countermeasures Following a Biological Attack (Dec. 30, 2009)

• DoDD 3025.12 – Military Assistance for Civil Disturbances, 4 Feb 94

• DoDD 3025.15 – Military Assistance to Civil Authorities,18 Jan 97

• DoDD 5111.13 – Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Defense and Americas’ Security Affairs, 16 Jan 09

• DoDD 5525.5 – DoD Cooperation with Civilian Law Enforcement Officials, 15 Jan 86

• CJCSI 3121.01B, Standing Rules of Engagement/Standing Rules For the Use of Force for U.S. Forces (S), 13 JUN 2005

• CJCSI 3110.07C, Guidance Concerning Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Defense and Employment of RIOT Control Agents and Herbicides (S), 22 NOV 2006

• Joint Pub 3-28 – Civil Support (14 Sep. 2007)

• Army Regulation 700-131 – Loan and Lease of Army Materiel (23 Aug. 2004)

• National Guard Regulation 500-1/ANGI 10-8101 – National Guard Domestic Operations (13 Jun. 2008)

• FM 3-07 – Stability Operations and Support Operations (6 Oct. 2008)

• FM 3-19.15 – Civil Disturbances (18 Apr. 2005)

• USNORTHCOM CONPLAN 3502 (S)

• USNORTHCOM CONPLAN 3600 (S)

• USPACOM CONPLAN 7502 (S)A. Introduction

Within civilian communities in the United States, the local government and the state have the primary responsibility for protecting life and property and maintaining law and order. Generally, federal forces are employed in support of state and local authorities to enforce civil law and order only when circumstances arise that overwhelm the resources of state and local authorities. This basic policy reflects the Founding Fathers’ hesitancy to raise a standing army and their desire to render the military subordinate to civilian authority. The basic policy is rooted in the Constitution and laws of the United States, and allows for exception only under extreme, emergency conditions.

The Constitution guarantees to the states that the Federal government will aid in suppressing civil disturbances (Civil Disturbance Operations (CDO)) and empowers Congress to create laws that provide Federal forces for that purpose.5 Other emergency conditions, which are outside the constitutionally and congressionally prescribed conditions, may also allow for CDO.

…

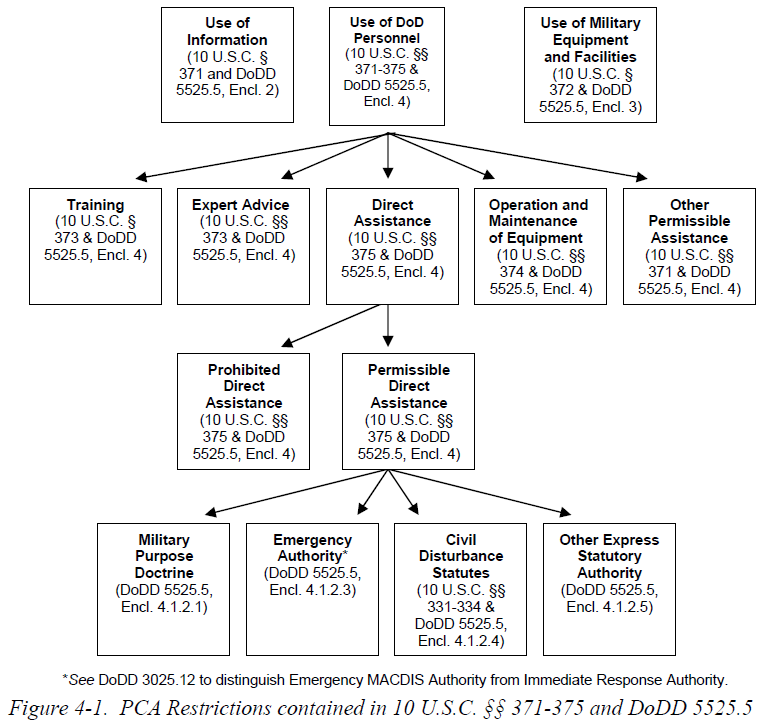

B. The Posse Comitatus Act

The primary statute restricting military support to civilian law enforcement is the Posse Comitatus Act (PCA). The PCA states:

Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or Air Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.

The PCA was enacted in 1878, primarily as a result of the military presence in the South during Reconstruction following the Civil War. This military presence increased during the bitter presidential election of 1876, when the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, defeated the Democratic candidate, Samuel J. Tilden, by one electoral vote. Many historians attribute Hayes’ victory to President Grant’s decision to send federal troops for use by U.S. Marshals at polling places in the states of South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. Possibly as a result of President Grant’s actions, Hayes won the electoral votes of these hotly contested states. The use of the military in this manner by a President led Congress to enact the PCA in 1878.

The intent of the PCA was to limit direct military involvement with civilian law enforcement, absent Congressional or Constitutional authorization, in the enforcement of the laws of the United States. The PCA is a criminal statute and violators are subject to fine and/or imprisonment. The PCA does not, however, prohibit all military involvement with civilian law enforcement. A considerable amount of military participation with civilian law enforcement is permissible, either as indirect support or under one of the numerous PCA exceptions.

…